BP to try unprecedented engineering feat to stop oil spill

- "Pollution containment chamber" could reduce leak by more than 80 percent

- Water pressure, greater than oil pressure, would help push the oil to the surface

- Workers still putting together the 100-ton, 40-foot-tall rust brown device

- Containment chamber could be in place by end of the week, BP official says

Port Fourchon, Louisiana (CNN) -- It sounds like a Hollywood movie. An impending disaster -- think the disabled spacecraft in "Apollo 13" or the asteroid hurtling toward Earth in "Armageddon" -- prompts a daring intervention by engineers to save the day.

This time, the threat is oil gushing from a broken well on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico that could destroy livelihoods and irreplaceable coastal wetlands.

Equally real is the attempted engineering marvel -- a four-story metal container that will be lowered onto the leaking pipe to try to suck in the flowing oil.

Officials of BP, the oil giant that owns the leaking well, said Monday they plan to try the unprecedented effort this week.

Explainer: Stopping the leak

Explainer: Stopping the leak

Video: Could oil spill push electric vehicles?

Video: Could oil spill push electric vehicles?

Video: Post-Katrina rebound threatened by oil

Video: Post-Katrina rebound threatened by oil

If successful, they say, the "pollution containment chamber" could reduce the underwater gusher by more than 80 percent and provide the first success in industry and government efforts to control the spill that began April 20 with an explosion and fire on an offshore rig.

"Everyone's committed to getting this stopped so we can just focus on a cleanup," said Doug Suttles, the BP chief operating officer.

KATC: Gulf shrimp season to temporarily close

The challenges are vast and varied, reflecting the scope of the problem.

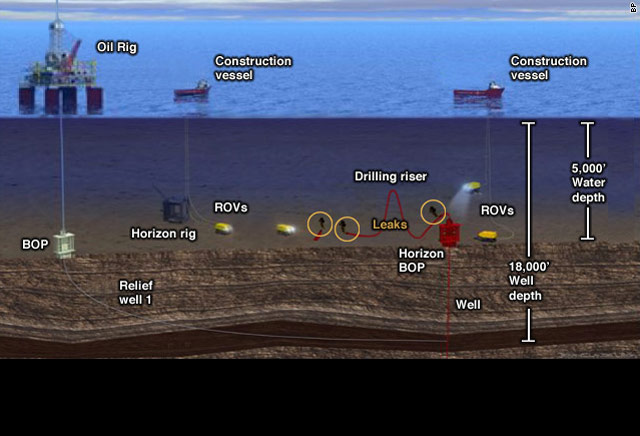

The gushing well is 5,000 feet under water at the bottom of the ocean, where the immense pressure makes it impossible for humans to work.

So far, unmanned submarines called "remote operation vehicles" have been trying unsuccessfully to fix a defective "blowout preventer" -- the failsafe gadget that should have prevented the leak in the first place.

Now BP has started drilling a relief well that eventually could allow them to close off the broken well. However, that would take at least two months to work, Suttles said.

KNOE: Community rallies around rig families

That leaves the pollution containment chamber, a 100-ton, 40-foot-tall rust brown device that workers were still putting together Monday in the Port Fourchon, Louisiana, workyard, where welders' torches showered sparks as gulls flew overhead.

It is the biggest such chamber ever constructed, BP officials say.

--Doug Suttles, BP chief operating officer

Their plan is to lower the chamber to the ocean floor where the biggest of three leaks in the well's underwater piping occurs. It would straddle the pipe and lock itself into the seabed, so that the leaking oil goes into the chamber itself.

Then the question becomes how to pipe it up to a giant tanker on the surface, 5,000 feet up. It is by far the deepest attempted use ever of such a containment chamber, according to BP officials.

"This has been done in shallow water; it's never been done in deep water before," Suttles said.

The engineers will rely in part on the laws of physics to their advantage, Suttles said. Because water pressure is greater than oil pressure, it should help push the oil to the surface, he said.

If all goes well, the containment chamber could be in place and hopefully pumping up much of the spilling oil by the end of the week, Suttles said.

BP workers also are building a smaller containment chamber for another leak in the pipe, he said, and hope to close a third leak with a shutoff valve as soon as Tuesday.

So far, an estimated 2.6 million gallons of oil, roughly 60,000 barrels, has spilled into the Gulf of Mexico, forming a slick the size of the state of Delaware.

The oil continues to gush at a rate of at least 5,000 barrels a day, authorities estimate, and the growing slick could come ashore at any time to destroy sensitive wetlands that are vital for the huge local fishing industry and other resources.

CNN's Tom Cohen contributed to this story.