At the end of this month, most of Ohio's teenagers will shake off their summertime blues, dust off their book bags, and head back to school. But others might be heading to an internship at a local newspaper or hitting the books for independent study. Some might even stay planted in front of the computer screen.

That's thanks to the state's new credit flexibility program, which Ohio is launching for the 2010–11 academic year. The plan puts Ohio on the front lines of a transition away from a century-old paradigm of equating classroom time with learning. But while there's a broad consensus that that measure, the Carnegie Unit, is due for replacement, no such unanimity exists about the design and prospects for plans like Ohio's. While most stakeholders agree that it's theoretically preferable to give students the chance to personalize their education, it remains unclear how effective the alternatives are, how best to assess them, and whether today's teachers are equipped to administer them.

"Certainly the Carnegie Unit needs undermining," says Chester E. Finn Jr., president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a Washington-based education think tank that also runs charter schools in Ohio. "It's far better to have a competency-based system in which some kind of an objective measure of whether you know anything or have learned anything is better. But by what standard will Ohio know that's been met?"

The Buckeye State's program will be among the most sweeping, but nearly half of the states now offer similar alternatives—although in many cases that's nothing more than allowing students to test out of classes by demonstrating proficiency. A smaller but growing number of states, from Florida to New Jersey to Kentucky, have begun allowing students to earn credit through internships, independent studies, and the like. It's a logical extension of the realization that simply being in a seat from bell to bell doesn't guarantee intellectual development. Students—and their parents—are at least theoretically attracted to the idea of studying what they want, at the pace they want.

Teachers are on board, too. "It really will allow more meaningful experiences for students," says Sue Taylor, president of the Ohio Federation of Teachers, a teachers' union that participated in designing the program. "Any time a student is able to take the lead or take some charge of some aspect, that student is going to be more motivated and learn something at a deeper level." The motivation will extend to educators, she says: many teachers complain that the controversial No Child Left Behind law forced them to "teach to tests," preparing students to pass inflexible multiple-choice assessments, but the new rules should make room for more creativity.

Of course, creativity can't preclude quality. "The concern is that the advocates of personalization don't necessarily advocate between good personalization and bad personalization," says Rick Hess, director of education policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. "A lot of these internships end up being time wasters, being silly, being trivial." While individual schools have found success with flexible systems, it's unclear how they will work when scaled up to apply to entire districts or states. Many states with provisions for internships and independent-study programs are "local control" states, meaning that while the state's Department of Education may mandate or allow high schools to give students options, the decision about what qualifies as a valid educational experience is left to local authorities. The bar could be set differently from city to city, school to school, or even teacher to teacher. Ohio, for example, hasn't offered solid guidelines to districts, although a spokesman says the state will collect data each year on how many students participated and what program they chose in order to "inform Credit Flex statewide going forward." It won't conduct a formal audit, though.

That's not enough for some observers. "That's an easy way for state officials to hide behind the mantra of local control and shirk authority," Finn says. In fact, it could run at cross-purposes to a push for the Common Core national curriculum standards, an effort President Obama has endorsed and which he discussed in a July 29 speech on education policy. "It's ironic that we're moving toward national standards even at the same time as we are freeing students to do what they want," Finn says. "How do [policymakers] reconcile the commonness and heavy intellectual standards they've adopted? I don't think it's going to be done well."

But while Hess agrees that the balancing act is delicate, he sees the two goals as complimentary. "We have to keep personalization from becoming abdication by making sure it's in the service of acquiring the skills we deem important," he says. "The Common Core can spell out things that we as a nation believe are essential, but then presuming we have ways of assessing to make sure we learn them, we should be agnostic about how." In practice, that means many states are using standardized assessments—an element of No Child Left Behind that many educators criticized—to ensure that pupils are learning the same baseline material, whether it's in the classroom or in the community.

Starting alternatives won't be easy in a difficult fiscal environment. With states across the country desperately broke, even basic public services like schools and police have been put on the chopping block. Hawaii, for instance, cut some school weeks to four days, giving students 17 Fridays off, in the last school year; the plan was massively unpopular. Even though Congress held a special session this week to pass a bill giving states $10 billion to keep teachers on the job, school districts are looking at lean times for years to come. The holy grail for superintendents and school boards will be to find ways to cut costs without slashing school days.

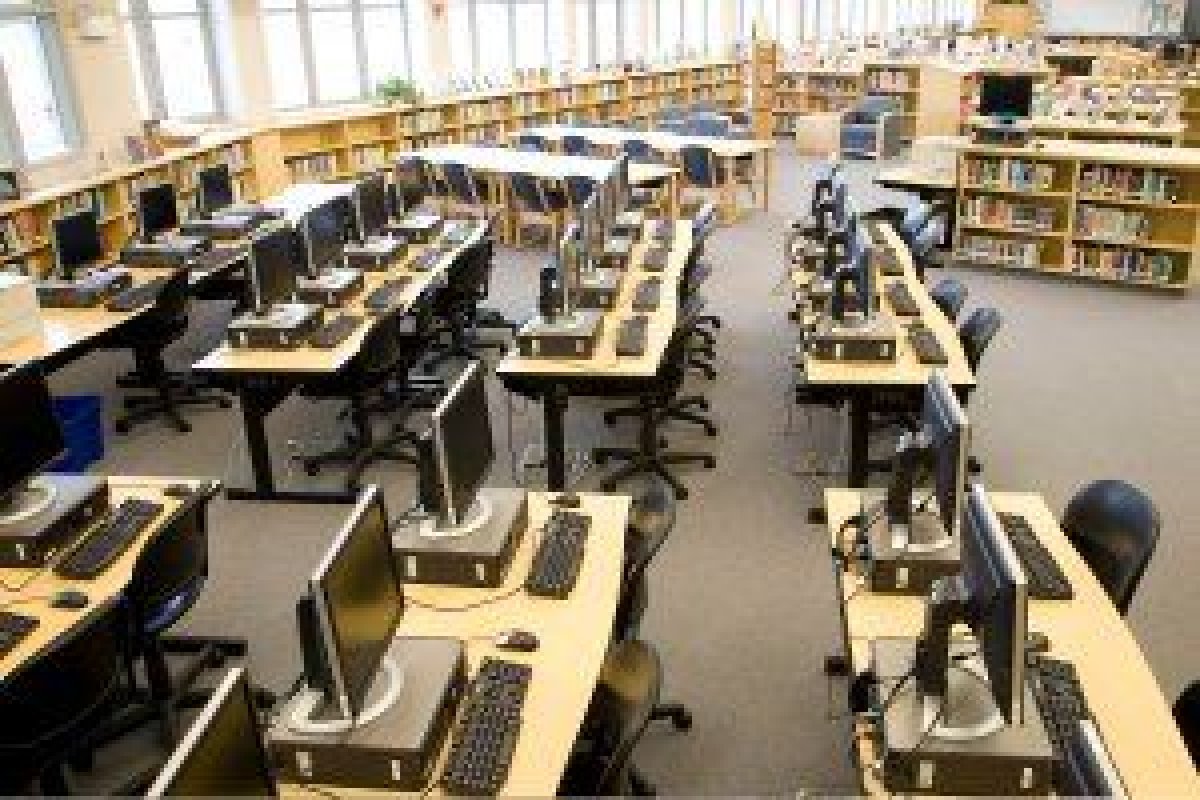

Florida's Credit Acceleration Program—which expands previous options for accelerated graduation—was passed this year with the primary goal of allowing students who are ready to move to tougher courses to do so. But it's also a handy way to save money, says Mary Jane Tappen, the state's deputy chancellor of curriculum, instruction, and student services. Fewer students in desks means cost savings. Virtual learning—which an ever-larger number of states allow as an alternative to learning in bricks-and-mortar schools—provides even greater economies of scale. The Florida Virtual School, an industry leader, has seen continuously increasing enrollment for both in-state and out-of-state students. Its Global School—the division that offers virtual classes to students outside of Florida on a fee model—does almost all of its business with districts and states rather than on an individual student basis, says Andy Ross, the school's chief sales and marketing officer. It's helped to subsidize the taxpayer-supported in-state division of the Virtual School as well, covering its own costs and contributing some $2.5 million per year for research and development of software and teaching methods).

While educators say blends of traditional and virtual learning are ideal, all-virtual classes could create an opening for strapped states to save money by slashing the ranks of teachers they employ in traditional classrooms. "If the same virtual lesson recorded in Seattle can educate 8,000 kids in Ohio, how many teachers might not be needed that Ohio has historically employed?" Finn asks.

Taylor, of the teachers' union, is concerned about budget cuts with the coming changes in Ohio. "There may be a few districts that are financially strapped in this climate who may see [credit flexibility] as a chance to see budget slashing, but if they do, obviously it's going to be done to the detriment of effective student learning," she warns. On the contrary, she thinks districts should hire more teachers, with some taking on more supervisory and advisory roles in overseeing credit-flexibility experiences. "If a teacher has 125 students in a day, it's not going to be feasible for [him] to help to design and work with each and every student," she says.

Of course, this may be irrelevant. In launching its plan, the Ohio Department of Education said a major reason for mandating that districts develop flexibility plans was that while many states provide flexibility, not many districts take advantage of it. Data collection nationwide is hit or miss, so it's tough to tell how many students use existing programs. Meanwhile, although anecdotal evidence suggests parent and student interest in the new alternatives, no one is offering predictions about how many Ohio students might sign up for Credit Flex. If the nationwide example holds, the vast majority of students will decide that bricks-and-mortar schools are still the best way to get their mortarboards.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.