I was just beginning to think that this long summer of intolerance was coming to an end. American hysteria about the non-mosque that's not at Ground Zero seems to be subsiding just a bit. The French government might be backing away from its ginned-up xenophobia amid reports the prime minister isn't really on board with the president's right-wing rhetoric. There's even a chance that peace talks between Israelis and Palestinians will get back on track at a summit in Washington next week. Whew. Then I picked up a copy of this morning's London Times and discovered a whole new reason for some people with old wounds to start hating each other anew.

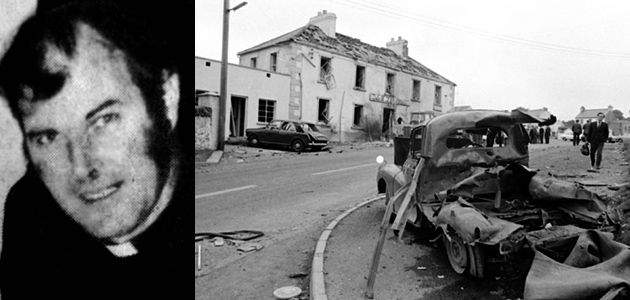

Splashed across two pages is the story of a Roman Catholic priest who appears to have participated in car bombings that slaughtered nine people, Protestants and Catholics alike, in the little village of Claudy in Northern Ireland back in 1972. Among the dead were a mother of eight, two teenagers, and a little girl. Police investigators concluded that the late Father James Chesney had a role in the act, and he may even have ordered it.

In the aftermath, church officials allegedly helped protect Chesney from prosecution—and colluded with British officials in the process. Their ostensible motivation was concern that public knowledge of a priest's involvement would have made that bloodiest year of the sectarian Troubles in Northern Ireland even bloodier. So the church hierarchy, typically, thought the best approach was to move him to another parish, out of the way and out of the reach of the law. Chesney died in Ireland of natural causes in 1980. In 2002, after the 30th anniversary of the attack, the case was reopened. But there has never been a conviction.

The basic account of these events and conspiracies is drawn from a detailed report published this week by the police ombudsman of Northern Ireland, Al Hutchinson. This is not rumor. It is the result of extensive government investigations, and the case it makes against Father Chesney and those who covered for him is, to say the least, damning.

So should we now think twice or three times about letting anybody build a Catholic place of worship or community center in our town? After all, if some priests are terrorists (not to mention pedophiles), aren't all Catholics suspect?

Of course not. But you get the point: it is the height of folly—and prejudice—to make a whole group of believers face angry abuse and protests because of the actions of a minuscule number of extremists and criminals. For many centuries, some Catholics and some Protestants, and some Jews and some Muslims, have been responsible for carrying out atrocities, convinced that they had a God-given right to murder anyone who got in their way. That should never be an excuse to condemn them all, even if some people see the terrorists as freedom fighters.

In Israel in 2002, at the height of the horrific Palestinian suicide-bombing campaigns there, I would return to my room at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem after visiting the scenes of carnage inflicted on innocent Israelis by Arab Muslim fanatics. The smell of a blasted-apart bus and charred flesh was still in my nose. Then I would turn on the TV, and there on the in-house video loop was a documentary extolling the bravery and commitment of the Jewish fanatics who blew up that same King David Hotel in 1946, killing 91 people in their fight against British occupation. Only about a third of the dead were actually British officials.

Front and center in that in-house video was one of the conspirators, Menachem Begin, who later became Israel's prime minister and clearly was regarded by the producers of the publicity film as a hero. Begin always claimed he tried to warn the people inside the building to get out, but the message went astray. As it happens, Father Chesney seems to have wanted to warn people about the Claudy bombs, too, in order to minimize casualties. But the phones didn't work. If you really care about sparing lives, bombs are not the best way to make your point.

Am I suggesting moral equivalency here? At one level, sure. As a moral absolute, the slaughter of innocents is the slaughter of innocents; it doesn't matter what cause or what god the murderers believe they are serving. It doesn't matter if they claim that their targets were "legitimate" and the other corpses were just accidents. The mindset of savage zealots was best articulated long ago by a priest advising the Crusaders who laid siege to the town of Béziers in 1209. The Christians there were protecting heretics. "Kill them all," said the pope's man on the scene, "and let God sort them out."

Maybe we should hate all religions not our own. Or, maybe we should hate all religions, period. Or—this is what one truly hopes—maybe it's time to spend less time hating.

We do not live in a world of moral absolutes, in fact. We live in a world of constant moral compromises. Some terrorist leaders become peacemakers. Begin was one example. Yasir Arafat was another, at least for a while. In Northern Ireland today, Martin McGuinness is the deputy first minister, a role vital to healing the wounds of so many years of terror, even though he was the Provisional Irish Republican Army's second in command in the area around Claudy when the bombs went off. (No group ever admitted responsibility, but police intelligence left little doubt it was an IRA job.)

In fact, the real task of making peace and keeping it among communities lies with the people, who often have more common sense and compassion than the leaders who work so hard to inflame their zeal and their violence. As Palestinians and Israelis meet next week, as the French step back to look at the storm their government's latest posturing has produced, and, yes, as Americans take a breath after all the shouting about Ground Zero, they would do well to look at what happened after the bombings in Claudy.

The town had only 400 people in it at the time. Everybody knew at least one of the victims; many people knew all of them. None was a target, really. The IRA apparently just staged the attack as a distraction, to take the heat off its people in the nearby city of Londonderry.

Did the Protestants and Catholics in Claudy turn on each other then? Did their rage pour into the streets? No. "People here have always lived in good fellowship with each other, irrespective of denomination," Protestant businessman Matthew Robinson, 73, told the Times. "After that, we found we needed each other more than ever." Robinson had a particular way of showing that. His building company supplied the materials for the construction of a new Catholic church in Claudy.

Christopher Dickey is also the author most recently of Securing the City: Inside America's Best Counterterror Force—The NYPD, chosen by the New York Times as a notable book of 2009.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.