Frida Kahlo is, in the words of one of her many scholars, the most famous painter in the world. Not the most famous female painter, not the most famous Mexican painter, not even the most famous disabled painter, though she was all those things. (Also: bisexual, a communist, and the consort of Leon Trotsky, among others.) There are two-hour lines to get into the Kahlo retrospective in Berlin. This spring, a very small, obscure landscape by Kahlo sold at Christie's for more than $1 million—10 times the estimated price. Even Google marked her 100th birthday (though it apparently didn't know that she fudged her age). "Having something from Kahlo," says Salomon Grimberg, author of the Kahlo catalogue raisonné, "is like having a sliver from the true cross."

So it would seem a trove of Kahlo's possessions—paintings, but also letters, diaries with sexually explicit doodles, sketches, recipes, dresses, and other knick-knacks, including a box of stuffed hummingbirds—in a few trunks in the back room of an antiques shop in Mexico should arouse great excitement among the Kahlo experts. Yet it wasn't until 2009, when The New York Times announced the forthcoming publication of Finding Frida Kahlo, a book cataloging this eclectic collection, that the art world took notice—and not in a good way. A dozen Kahlo experts signed a letter denouncing the archive. The trust that controls Kahlo's copyright filed a criminal complaint demanding that the Mexican government investigate the origin of the works and attempted to block publication of the book. According to the small group of dealers, scholars, and experts who consider themselves the guardians of Kahlo's legacy, the archive is fake, and the couple who own it are either perpetrators or victims of one of the greatest art hoaxes in history.

Carlos and Leticia Noyola hardly seem like big-time art fences. They live in San Miguel de Allende, a small city in the interior of Mexico, where they run an antiques shop in a factory that has been converted into an indoor mall of art. In their capacious, cluttered store, La Buhardilla (The Attic), you can browse for religious statues, tiny votives, or ornate armoires that span almost an entire wall. Up until recently, the Kahlo archive was stored in a back office, though the Noyolas would gladly show it to tourists.

The Noyolas claim they have no intention of selling their collection and would like it go to a museum. According to the couple's reasoning, the experts are trying to discredit the archive because the raw nature of the contents threatens the popular idea of Kahlo's life and work. The Noyolas say it's time a small group of dealers and scholars stop controlling the artist's legacy. "The experts just know the Frida that was public," says Carlos Noyola. "This is the controversy: we have the real Frida, the personal and intimate Frida, and they have the Frida created by the New York market." The experts maintain that when it comes to suspected forgeries, works are guilty until proved innocent, and the Noyolas simply cannot prove their archive is real. Whatever the Noyolas have, they say, it's not Frida.

Authenticating artwork involves three factors: provenance (the paper trail of how the work got from the artist to the owner), connoisseurship (the opinion of experts), and science, with testing usually coming into play only after the other two factors have established a likelihood that the work is authentic. In the case of these Kahlos, the provenance is shaky. The Noyolas say they bought the archive from a lawyer who had acquired it from a woodcarver who worked for Kahlo's husband, Diego Rivera. The Noyolas have a letter to the woodcarver from Kahlo, offering him the archive as payment for work he'd done, but the experts say no independent documents link him to Kahlo, and the letter must be fake.

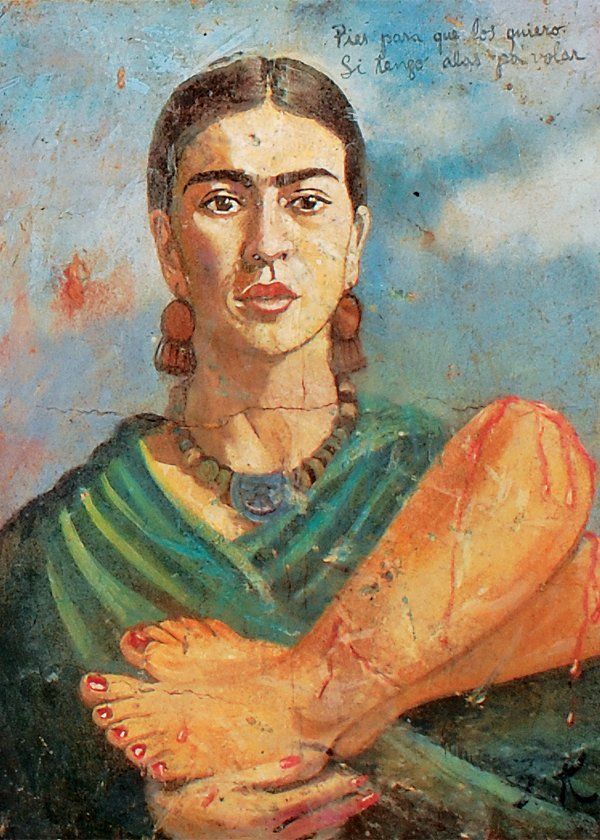

One of the most vocal critics of the archive is Mary-Anne Martin, a dealer who founded the Latin American art department at Sotheby's and has owned and sold many Kahlos. Martin was one of several experts who, along with the Noyolas and the publishers of Finding Frida Kahlo, attended a symposium about the controversy put on by the Dallas Art Fair in March. It was the first time Martin had seen the works in person. At one point she was asked to take a close look at a disputed painting. The work depicts Kahlo holding her own amputated legs—a typically autobiographical image born of the childhood polio that led to her having her lower right leg amputated shortly before her death. According to Martin, the painting was "even worse than in the photographs" reproduced in Finding Frida Kahlo. Nearby, James Oles, a professor of art history at Wellesley and the author of books on Mexican art, was discussing the works in a mixture of English and Spanish. A crowd gathered. "My opinion is simply that you have been deceived," Oles told the Noyolas after looking at a painting. "I don't have any doubt these are fake." Leticia Noyola asked Oles about scientific testing that had dated the materials to Kahlo's lifetime. "I don't care about science," Oles said.

Martin's and Oles's attitudes are not uncommon in the world of art authentication. In the documentary Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock?, Thomas Hoving, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is shown examining a disputed Pollock that a truckdriver bought at a thrift store for $5. He scrunches his face, wrinkles his brow, stands close, stands back, and does everything but lick the canvas. Finally he pronounces his judgment: it's a fake. Why? It just "doesn't feel like" a Pollock.

For each of the major (dead) artists whose works sell for millions of dollars, there are one or two experts (sometimes related to the artist) who have the authority to issue certificates of authenticity or to deem the works worthy of further study. The basis for these judgments can sound surprisingly touchy-feely, involving words like "energy" or "it didn't speak to me." The experts say that this intuitive reaction is supported by a deep knowledge of the artist's materials, brushwork, color palette—even whether he or she was right- or left-handed. Though there have been cases of expert-authenticated works later proved to be fakes, there have also been cases of experts catching mistakes forensic tests missed.

The Noyolas have sent several items from their collection to the McCrone laboratory in Chicago, a consulting firm that uses microscopes and chemistry to examine the composition and age of items. It was McCrone that determined that stains on the Shroud of Turin were actually made of red ocher and vermilion tempera paint, and that a manuscript of the Gospel of Mark believed to be from the 14th century contained Prussian blue paint, as well as the chemical lithopone, which dated the manuscript to the 18th century at the earliest. Because the Kahlo case is under investigation by the Mexican government, the Noyolas won't reveal the test results, but they seem confident that they will be vindicated.

As with most contested works of art, the dispute over the Noyola archive comes down to a battle between the true believers and the unmovable skeptics. In addition to the Noyolas, the believers' camp includes a handwriting expert who claims the writing in the letters matches Kahlo's, as well as Diego Rivera's granddaughter, who attested to the authenticity of the work before her death in 2007. A pair of artists who were close to Kahlo are also convinced. Arturo Bustos was among the group of Kahlo's students known as the Fridos; his wife, Rina Lazo, was Rivera's assistant. In a drawer in her bedroom, Lazo keeps a skirt Kahlo gave to her. A bookshelf holds signed photographs of Bustos with Kahlo. Now in their 80s, Bustos and Lazo continue to make their own art, but much of the couple's lives has been dedicated to preserving and propagating the Kahlo myth. Over the years, they've issued several certificates of authenticity for Kahlo works, and they were among the first people to see the Noyola archive.

Bustos didn't have that intuitive flash of recognition the experts describe; in fact, he was struck by how different the paintings looked from Kahlo's work. "He thought, they are not masterpieces, not finished like the paintings we knew of Frida," says Lazo, translating for her husband, who refers to Kahlo as maestra (teacher). But just because they weren't finished didn't mean they were fakes, she adds. "As a painter sometimes you just draw, and you think, nobody will see that."

It sounds like a shaky justification—if Kahlo never intended anyone to see the works, why did she give them away? But it's true that not all artists' works are masterpieces, or even immediately recognizable as the artist's style. Survivor, the small Kahlo landscape that recently sold at Christie's, bears little resemblance to the artist's best-known works—it even lacks a signature. "Looking at it from across the room, I would never think it was a Kahlo," says Katharine Nottebohm Brooks, a specialist in Latin American art at Christie's. But unlike the Noyola collection, Survivor has extensive documentation: it was mentioned in a New Yorker story from 1938, and is listed in the catalog of a show from that year.

If the Noyola archive is conclusively proved to be forged, the question is who would spend the time to create such a vast and idiosyncratic collection. The skeptics agree that it was most likely made by several people. Because Kahlo lived in a house with many servants and their families, and other artists were often coming and going, it's possible that at least some of the items could have been made by others. "If you start reading the documents, they're full of spelling errors," says Martin. "Frida was an educated woman. I have a nice collection of her letters. I know her handwriting. She's salty, but not vulgar. These things are very coarse. There are lots of people who knew Frida's story. People could be sitting around in some room manufacturing these things using details from her life."

Unless a remorseful forger (or group of forgers) comes forward, it's unlikely we'll ever know for certain who made all the items in the archive. Despite what programs such as Antiques Roadshow or even CSI may lead us to believe, forensic testing is much better at undermining a painting's legitimacy than proving authenticity. Advances in scientific analysis mean we can know in great detail how and when and where a painting was made, but science still can't tell us who made it. In art, there is rarely a smoking gun linking an artist to a work, and for nearly every legitimate sign of aging, there's a way to fake it. Letters can be stained with tea to appear older than they are. Paintings can be baked in an oven to create surface cracks, which can then be rubbed with dirt and grit to simulate age. Or a modern-day forger can use old materials to create a new work.

In the mid-1980s, the Getty Museum paid $7 million for a kouros, a small Greek sculpture, after extensive scientific testing determined the marble had come from a Greek quarry hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago. But soon experts began questioning the statue's authenticity—according to one, the piece inspired "a wave of intuitive repulsion"—and it is now listed in the Getty catalog as "Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery."

Today, most major museums not only acknowledge they have fakes in their permanent collections, they celebrate them. A recent show of known fakes at London's Victoria and Albert Museum was held over due to popular demand, while a similar show is currently on view at London's National Gallery, suggesting the "art" of forgery is starting to be taken seriously. After all, for almost as long as artists have been making art, others have been copying them. Renaissance artists employed assistants who did much of the actual work on their paintings and sculptures; Dalí signed blank canvases; both Picasso and Corot would sign forgeries they thought had sufficient merit. Other times, work that was never intended to be mistaken for the real thing (such as splatter paintings "in the style of" Jackson Pollock used by interior decorators) find their way into the market—and are assumed to be lost masterpieces. And plenty of works are straightforward forgeries, intended to deceive collectors' eyes and pocketbooks.

Just in July, a box of glass negatives bought for $45 at a garage sale was attributed to Ansel Adams and valued at $200 million. Adams's family, along with several dealers, immediately denounced the negatives as fakes, and now the trust that controls the rights to the photographer's work is suing to block their sale. As with the disputed Kahlos, the Adams case is fast becoming as much about who knew the artist best as it is about the art itself.

But how, then, to explain the experience of people who have been profoundly moved by works later discovered to be fakes? In The Man Who Made Vermeers, about the forger Han van Meegeren, Jonathan Lopez writes, "Although the best forgeries may mimic the style of a long-dead artist, they tend to reflect the tastes and attitudes of their own period. Most people can't perceive this: they respond intuitively to that which seems familiar and comprehensible in an artwork, even one presumed to be centuries old." People who know Kahlo's story may look for confirmation of it in her art; what they respond to is not a glimpse of the artist, but a glimpse of themselves.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.