With the web, curiosity and luck, sperm donor siblings connect

- Sperm donor siblings are finding each other through the web and building relationships

- There are an estimated 30,000 to 60,000 children born each year through donor sperm

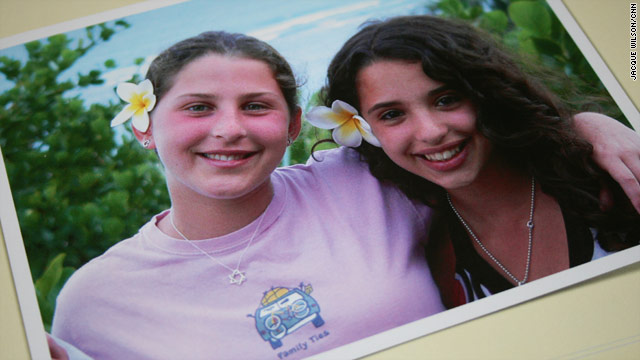

- The Jacobson and Clapoff twins discovered they were donor half siblings in 2007

- The two sets of twins communicate often and vacation together

Marietta, Georgia (CNN) -- The two sets of 15-year-old twins on opposite sides of the country share a lot of similarities.

Ask all four of them their favorite food, they will say sushi. Ask them about an annoying habit, they will say they bite their nails. They describe themselves as athletic, outgoing and open-minded. They have brown hair, full lips and broad hands.

They are also the biological offspring of sperm donor No. 1096.

Fifteen years ago, sperm donation enabled two mothers to give birth to the children they always wanted. Now the internet age has allowed their twins -- Jonah and Hilit Jacobson in Georgia and Jesse and Jayme Clapoff in California -- to find each other.

Their connection happened partly from persistence and partly from luck in 2007. The two families had joined the Donor Sibling Registry online, where they found their half siblings by searching for families with a matching donor identification number.

These aren't the most conventional sibling relationships, but the teens are gradually forming friendships and growing closer, the siblings say. Today, 12 offspring from sperm donor No. 1096 have connected through the site.

"We miss you!" says Hilit, the female twin in Georgia, outfitted in a in a tie-dyed tank with her fingers adorned in shiny rings with peace signs. "How are you?"

Her brown eyes peer into her silver Mac with her twin brother, Jonah, sitting next to her. They are video-chatting with their half siblings in California. On the screen, Jesse, their donor half brother with cropped short hair, tells them about his recent Costa Rica surfing trip.

They chat like this, by video, once a month and text and Facebook message every few days. They also vacation together about once a year.

The two sets of twins are probably the closest of the 12 donor siblings, even though they live thousands of miles apart, they said. Their friendship formed immediately after they met at the Jacobsons' home in Atlanta, Georgia.

"It's like your best friend but a different kind of bond," said Jonah, who is tall and neatly dressed in a Polo shirt. "You have that feel."

Sperm donor children come out

The anonymity in the world of sperm donations is fading as donor children collide on the web.

Becoming a sperm donor

Becoming a sperm donor

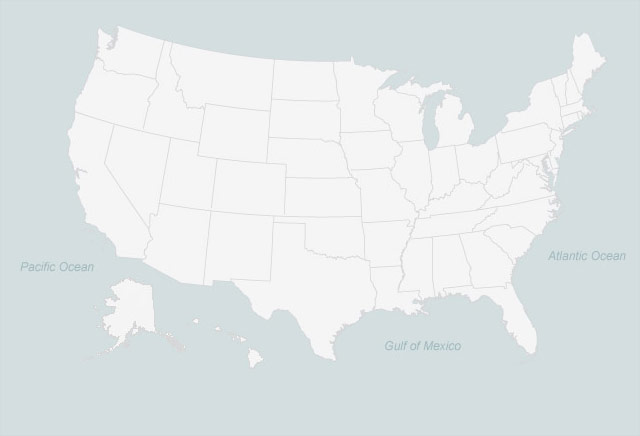

Where are the donor siblings?

Where are the donor siblings?

Many of the donor sibling connections -- about 7,300 of them including the Jacobsons and Clapoffs -- have been made through the Donor Sibling Registry, a voluntary website that matches donor siblings based on identification numbers. Occasionally, the site brings the children and the donor together.

Wendy Kramer, 51, who had her son Ryan in 1990 with donated sperm, created the site in 2000. At the time, her 10-year-old son was curious if he had donor siblings.

"We realized there was no way to make mutual consent contact. There was no way for anyone to get in touch," said Kramer, who eventually found her son's half sisters through the site. The sperm donor siblings recently spent the Fourth of July together.

Studies estimate 30,000 to 60,000 children are born each year with the help of donated sperm. The estimate is rough, because sperm banks and clinics aren't required to report their birth figures. Overall, the billion-dollar sperm banking industry remains unregulated, reproductive technology experts said.

California Cryobank, the largest sperm bank in the country, said that 60 percent of the sperm donor births are reported from the sperm they distribute. The number of related offspring from a single donor usually doesn't exceed a dozen, Kramer said, but she has seen as many as 50 donor offspring discover they have the same donor on her site.

"It's an important therapeutic option for some people for family building," said Sean Tipton, spokesman for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Over the last decade, sperm donor conception has come out of the closet, several families said, perhaps because of the growing diversity of American families shaped by adoption, divorces, single mothers and same-sex couples.

Recent Hollywood movies have explored the lives of donor children. The film "The Kids Are All Right," starring Julianne Moore and Annette Bening, tells the story of teenage children conceived through sperm donations who seek and get to know their donor father. Jennifer Aniston's latest movie, "The Switch," to be released next week, chronicles a single woman who uses a sperm donor to get pregnant.

"When you see things appear in pop culture, I think it really suggests a shift in acceptance," said Scott Brown, a spokesman for California Cryobank.

The fact they were conceived from donated sperm was never hidden from the Jacobson twins. Terri and Eric Jacobson told their children they were conceived with a donor when the twins began talking. The twins say their friends, neighbors and teachers have all been accepting of their untraditional family structure.

"If you're going to have this great relationship between you and the kids, there has to be honesty," said Terri Jacobson, 47, who chose to use a donor when she learned her husband, Eric, was sterile in the early 1990s.

'A family is what you make it'

On the day Eric Jacobson, 48, learned he couldn't produce children, he felt like he lost a child he never had, he said.

The Jacobsons considered adoption, but the process was too expensive. Terri Jacobson had also wanted to be pregnant. She happened upon information about sperm banks in a library book.

"It was the best alternative," the Jacobsons said.

--Jonah Jacobson, 15, sperm donor sibling

The sperm donation industry has become increasingly specialized. With California Cyrobank's Donor Look-a-Likes program, a parent can try to engineer their child to have traits from someone who resembles Zac Efron or Brody Jenner. The dating site called BeautifulPeople.com launched a sperm and egg bank this summer for "an exclusively beautiful community."

Physical looks weren't the priority for Terri and Eric Jacobson. They were more concerned that the donor was Jewish like them. But they did pick some traits that resembled Eric, such as being tall and having curly brown hair. Using a donor also allowed them to attempt to fill in traits the couple lacked, such as sharp mathematical skills, musical abilities and athleticism.

The traits the couple selected are apparent in their twins. Hilit pole vaults and runs track. Jonah plays baseball and the drums. They like math, too.

A June study from the Institute for American Values examined the struggles donor children face. The study re-explored a decades-long debate about anonymous donors: Should donor children have a right to know where they come from? Does the donor have a right to protect his privacy?

Elizabeth Marquardt, lead author of the study, said many donor children want to know more about their origins. She discovered through interviewing 485 donor children that many felt confused and isolated about their conception. About 65 percent surveyed believed the sperm donor is "half of who I am."

"It really speaks to how your biological kin matters to you," Marquardt said. "Whoever is raising you could be a loving family, but we are made of bodies. We want to know who these people are -- not just have a file on them. It's a key human longing."

The Jacobson twins said they don't want to know or meet their sperm donor.

"I already have a dad," Hilit said.

Jonah chimed in, "I have no desire to meet him. Maybe I'd like to see a picture of him, but that's it."

A family isn't just about biological connections in the Jacobson household.

They said, "A family is what you make it."

From the perspective of a donor

Todd Whitehurst donated his sperm while he was in graduate school at Stanford University in 1991.

He needed the extra cash and wanted to help people who couldn't have children. He applied to become a donor at California Cryobank.

Like many young men, the money from the donations went to pay for bills during school. He said he didn't think much about what happened to his donated sperm after he graduated.

Then three years ago, he received an unexpected e-mail from a child conceived from his sperm. The 14-year-old girl revealed to him the donor identification number from her file.

She had done some detective work on her own to find his e-mail. She was excited to learn that her donor identification number matched his.

Whitehurst was already the father of two children when he received the e-mail. Still, he chose to have a relationship with the 14-year-old girl. Over the years, Whitehurst has been contacted by two more of his donor offspring through the web.

The three donor siblings and Whitehurst have formed a bond. He takes the donor offspring and his own children on vacation together. He said the children all get along.

"They don't expect anything undue from me," said Whitehurst, now a 44-year-old physician, adding that, "They don't expect me to show up and become a full-time dad. I like to get together with them, and the great thing is my two kids like them, too."

But some reproductive technology experts said a generation of sperm donor children easily connected by the web comes with challenges. Not all sperm donor offspring want to get to know their half siblings or the sperm donor, said Susan Crockin, an attorney and reproductive technology expert in Massachusetts.

"What if someone and their family don't want to be a part of an unexpected family?" Crockin said.

At least one of the families the Jacobsons' encountered through Donor Sibling Registry decided not to pursue a relationship with their twins.

"Some really want to meet us," said donor twin Jayme Clapoff. "Some don't want to meet us. When I found out a sibling didn't want to meet us, I wonder why, because we are brother and sister, but I can understand it can be overwhelming. They are living their lives and suddenly these new people are in it."

--Sue Crockin, reproductive technology expert

Most half siblings have been receptive to the Jacobson and Clapoff families. Since they first connected in 2007, they discovered more siblings through the site.

They found another set of twins in Boston, Massachusetts and a half sister in Reno, Nevada.

There are five more siblings scattered across the country.

They have stayed in touch with the new siblings through trips, like their vacation to Hawaii, where they snorkeled and ate fresh fish on the beach. Two summers ago, the half siblings stayed at a cabin in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They spent the days grilling and the nights watching reality television and movies together. Eight of the donor siblings gathered at the Jacobson twins' B'nai mitzvahs a few years ago.

"You always have someone you can fall back on," said Jonah of his half siblings. "And not many people have that."