Melvia wants to make something very clear: She joined the rebels to kill—not to boil manioc or perform other chores usually dumped on women. She wanted to fight back against the men who attacked her village in the Central African Republic, torched her home and killed her grandmother. "I didn't join the group to cook," she says. "I wanted to do the hard work."

Melvia was one of several women in her militia's battalion and one of an unknown number bearing arms in the country's long-running conflict. There are 14 armed groups fighting for control of territory and resources in a crisis that the U.N. has said shows the warning signs of genocide. The vast majority of rebels are men, but many women like Melvia have taken up arms on all sides of this struggle. Their existence is often unknown to, denied or questioned by officials and aid workers, who assume rebel groups in such a male-dominated society would not allow women to fight. Contrary to stereotypes and suppositions, though, women have been in combat here.

Cracking the knuckles on her left hand, Melvia describes her weapons training—learning how to assemble and disassemble AK-47s and rifles, as well as her guard-duty shifts, patrols and trips to the front line. Casting a cool gaze skyward, she lists the times she fired her homemade weapon. Melvia guffaws at the suggestion she was anything but a full-fledged fighter. "We were treated just like the other soldiers. Like the men," she says. "I was allowed to give orders—firm orders—just like the others."

(Newsweek agreed to identify Melvia and others in this story only by their first names to avoid retaliation and stigmatization.)

Conflict has gripped the Central African Republic for more than four years, since a majority-Muslim coalition of rebels known as the Séléka overthrew the government. They committed atrocities, killing scores of civilians, burning homes and stealing property, on their path to seizing the capital, and largely Christian militias called the anti-Balaka rose up and fought back. The ensuing sectarian violence killed thousands.

The Séléka were ultimately ousted from the capital, but the country is far from stable. The Séléka splintered, and various armed groups now control most of the country. Violence surged again late last year and has been escalating ever since, prompting the U.N. to warn of a tipping point in a "forgotten" crisis.

'We Found Only Corpses'

Women are clearly a minority on the front lines here, and many of the women associated with armed groups are forced into marriage, face sexual violence and do occupy "traditional" roles of cooks or cares. But experts say acknowledging the more active role of some women is critical to achieving peace and stability and helping those women find a productive role in society. "War has always been a synonym of masculinity, of power…but only now is everyone realizing that women are a critical part of this," says Alejandro Sánchez, a policy specialist with U.N. Women, which works for the empowerment of women. "So if we really want to promote peaceful societies and really achieve sustainable peace, we also need to deal with women who are involved in these settings, these armed groups."

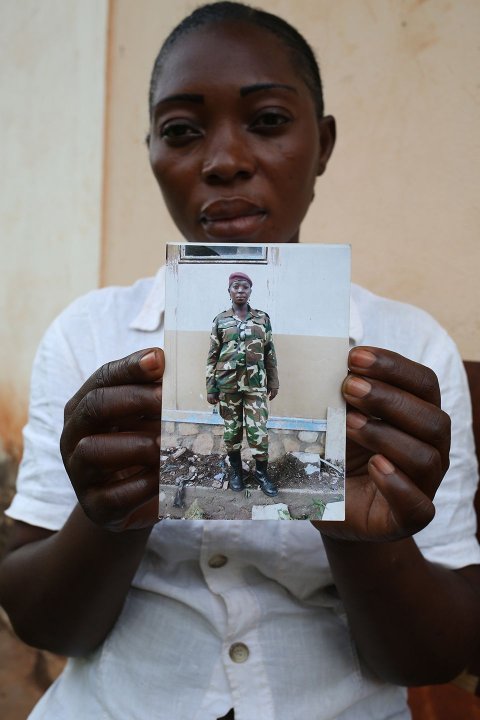

In the strategic town of Bria, Mariame's commander calls her "him"—and she's fine with it. She has the same uniform, same weapon and same job as the men: to fight. "They treat me like a man," 21-year-old Mariame explains of her fellow rebels, half a dozen of whom are clambering onto a pickup truck mounted with a machine gun behind her. "I'm not scared." Smoothing her skirt as she spoke on a day off from patrol duty, she adds: "I'm going to defend my country."

Just over a mile down the road is the makeshift base of a rival armed group, and Leticia is there to fight, too. "There's no difference between us. I work like everyone," Leticia says, nursing a baby as the men around her with rifles nod. "When we are attacked, and the men want to go out and defend, I go with them."

Among the many misconceptions surrounding these female combatants is that they were all forcibly recruited. While there are many such horrific cases, many others volunteered—and, like men, have diverse motivations for taking up arms, ranging from revenge to curiosity, a desire for power or a need for discipline.

For Stevia, joining an armed group was all about revenge. She'd been in the market with her mother selling vegetables and spices when Séléka fighters arrived and started firing in all directions. The soft-spoken 17-year-old describes the chaos that followed, how she and her mother fled to a farm while rebels tore through their town. "The Séléka group was going through our neighborhood killing people in houses," she recalls. "My father and others were in the house. When we came back, we only found corpses."

Her older sister also survived the assault—and later remembered hearing about fighters called the anti-Balaka who were taking on the Séléka. And so the sisters set out to find them. "We were so angry that we wanted to join the group in order to avenge my father," Stevia says, insisting it was her choice. "Even though we did not know who exactly killed our father, we just decided to go and kill any Séléka member we encounter."

They headed into the bush, in search of an anti-Balaka camp. "We found many other people—including many girls—in the group. That also encouraged us to join," Stevia says.

The anti-Balaka were initially skeptical, asking Stevia and her sister what they wanted. "We explained to them what happened to our father. They told us: 'If you are not afraid, you can join us; but if you are, then you should just leave.' We told them that we were ready," she explains, and they were in.

Stevia's sister told her she was too young to go to the front line, and urged her to stay behind and help with the cooking. "But I refused," Stevia says. "I wanted to go to combat."

While poverty drove her and her sister to eventually leave the group, Stevia says she still thinks about her father's death. "I'd be ready to join another group because the need for vengeance is still there," she says. "It's not been satisfied."

A Real Soldier

There have been several attempts to disarm rebel groups in the country and encourage combatants to reintegrate into society—a process the U.N. and others refer to as "DDR," which stands for disarmament, demobilization and reintegration. One such program, launched in October 2015, registered 737 women among the 4,324 combatants who took part, according to the U.N. A smaller-scale "pilot" project was launched by the government with the U.N. peacekeeping mission's support in August, with each armed group proffering a select list of names. Just six of the 109 combatants disarmed in Bangui in September for the pilot project were women. Two of the 20 disarmed and demobilized weeks later in the town of Bouar were women.

"Experience has shown that most DDR processes have not taken into account the women's needs," Sánchez says. He says DDR programs tend to treat women like dependents rather than willing participants in the fight. If women are viewed solely as victims, cooks or cleaners, reintegration programs can reinforce stereotypes about traditional roles by pushing women back into those areas, instead of taking into consideration their combat experience or training, and what they want to do with their lives.

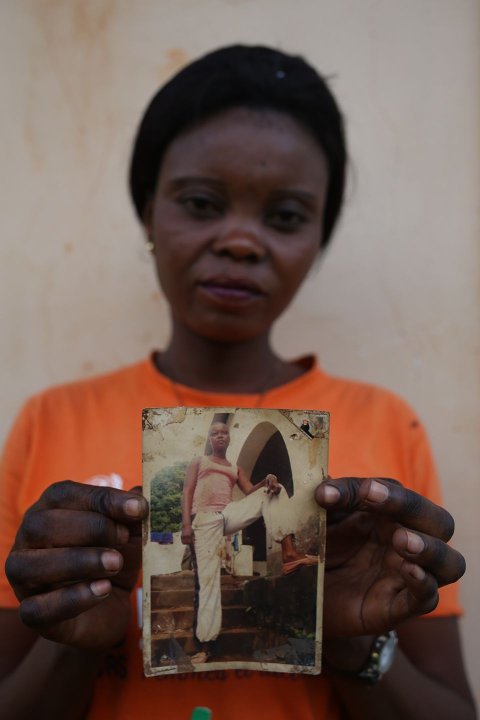

Take the case of Esther. Wearing a rhinestone-encrusted vest over a striped shirt that shows off her strong arms and shoulders, she explains that she always wanted to be in the army. When the Séléka seized power in Bangui, joining their ranks was the only path to becoming a soldier. "They trained us to be soldiers who would serve the country," she says. "I was hoping to get a good military training in order to become a real soldier with a good salary."

The training wasn't easy. There were drills—sprints, crawling through the mud, obstacle courses and endurance tests. But there were many women training along with her, she says.

Esther says she threw herself into her training, fighting through injuries and fatigue to beat her fellow recruits in running drills. "If you were strong, you would win. I was strong, so I won," she says proudly.

She scoffs at those who think women cannot be soldiers.

"I consider myself a female soldier because I know how to hold and use a gun," the 26-year-old says, adding with a smile: "Female soldiers can be brutal."

But for all of that hard work, Esther has nothing to show. The Séléka aren't in power anymore, and her dreams of a military career have been snuffed out. "I did not get anything out of it," she says, her gravelly voice going quiet. "All those years with them—it was time wasted. I wasted my time and didn't end up with anything, or a job."

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.