Four days before Christmas, armed Seleka rebels went door to door in Rosen Moseba’s* neighbourhood. She gathered her three children and, together with her brother, they ran for their lives.

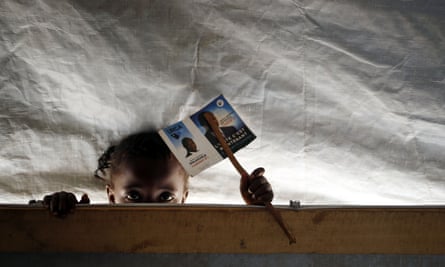

It was 2013, and Central African Republic’s capital, Bangui, was in the grip of violent chaos. The Seleka, a coalition consisting predominantly of Muslim fighters, had overthrown the government in March that year, prompting Christian vigilante groups – the anti-balaka – to retaliate. Amid killing and looting, communities on both sides were terrorised.

As Moseba and her family tried to escape, they were stopped by armed men. “There were a lot of rebels,” she remembers. “Three of them raped me, one by one. After they raped me some of the Seleka said, ‘Let’s kill her’. Others said, ‘No, no we are not going to kill her, we have already done what we want to do.’”

She was pregnant at the time. “I tried to resist but I couldn’t do anything because they had guns, and I had nothing,” says Moseba. They killed her brother in front of her and her children. She was forced to leave her brother’s body on the roadside. “I don’t know what happened after, I don’t know if someone buried my brother,” she says.

The capital is under government control today, but relations between Muslims and Christians remain tense. Many, like Moseba, have received little help to rebuild their livelihoods. Having lost everything in the crisis, she is unable to afford rent or pay for her children to go to school. Her husband left her after hearing that she had been raped.

Five years since conflict in CAR began, half the country’s population needs humanitarian assistance, while more than a million people have been uprooted by fighting. In many areas the crisis has deepened over the past 12 months.

Violence between armed groups, often competing for natural resources in a context of complete lawlessness, has overlapped with long-standing ethnic rivalries and distrust between the Christian majority and the Muslim minority. The UN’s emergency relief coordinator, Stephen O’Brien, has spoken of “the early warnings of genocide”.

Since the end of 2016, violence has erupted in almost every region outside the capital, according to a report by International Crisis Group. The centre and the east have been wracked by territorial conflict while, in the south-east, fighting has spiralled following the departure of American special forces and Ugandan troops assigned to fight the Lord’s Resistance Army.

The situation in the north-west – where fighting is underlined by ethnic rivalry between farmers and cattle herders – is also a growing concern. Thierry Vircoulon, who has conducted research for the NGO Mercy Corps, warns the government should urgently intervene in the region to prevent the escalation of violence ahead of the dry season, when herders move cattle from Cameroon to CAR.

“It’s becoming more and more of a community conflict. That’s making the conflict more and more difficult to manage because it’s fragmenting along community lines,” says Vircoulon. In communities let down by the UN’s chronically under-resourced peacekeeping mission, armed groups, which have splintered and multiplied, are increasingly seen as protectors.

Last month, the UN announced the deployment of 900 extra troops to CAR, but it is unlikely this will make much difference on the ground. “There will never be enough troops to cover the entire country. It is a huge country with very poor infrastructure and with a population scattered everywhere in a territory that is bigger than France,” says Enrica Picco, an independent researcher on the central African region.

The UN peacekeeping mission, Minusca, is widely seen as a failure. Dogged by reports of sexual exploitation and abuse, it is viewed by many in CAR as either ineffective or biased. Visiting the country in October, the UN secretary general, António Guterres, repeatedly said troops had no agenda beyond restoring peace. Guterres also criticised those who “use political manipulation to divide communities of different religions”.

The relationship between the UN and the government has become strained, says Jean Félix Riva, chief of staff for the special cabinet of the president of the national assembly. “What we are hearing when the prime minister speaks or the president speaks [is], ‘We are working with the UN and working with Minusca’, but in private they will tell you that Minusca doesn’t help to resolve the problem. When you meet the UN and Minusca in private they say the same thing.”

Despite last year’s elections, which were mostly peaceful and brought renewed optimism, the government has not done enough to unite the country or condemn violence driven by ethnic rivalry, says Picco. Meanwhile, the humanitarian crisis continues.

“The humanitarian space has been shrinking rapidly over the past few months, with many areas of CAR now simply too dangerous to reach, leaving thousands without access to emergency assistance,” says Levourne Passiri, who works for Tearfund in CAR. “While Bangui remains relatively calm, tensions have been rising in recent weeks as a result of several security incidents.”

Last month, Médecins Sans Frontières evacuated all national and international staff from Bangassou, a town in the country’s south-east, following a violent armed robbery. Thirty children in intensive care in the Bangassou hospital have been left without medical care.

Even in areas where aid workers can operate, resources are limited. Prudence Lamba*, from Bangui, was one of 100,000 people who lived amid the abandoned, rusty planes in the city’s airport, after fleeing the Seleka with her four children and 10 grandchildren. “When I had to run I left everything behind me. I just ran away, I left all my possessions,” she says.

The government closed the camp where she was living in January. Families were given 50,000 Central African Francs (£66) to return home, but the money is nowhere near enough, she says, even when her income as a wood seller is included. “I have to take care of my children and grandchildren. The children need to go back in school but I don’t have the money to pay for school or books or pencils,” says Lamba.

She worries about the psychological impact the crisis has had on her family. “It was very difficult for the kids. Before, we used to live in a house with walls. In the camp, we slept under a tent. Sometimes it was cold, sometimes there were bad animals, insects, under the tent. We slept on the ground, we didn’t have a bed. Due to the mosquitoes the children got really sick, mostly of malaria.”

It was impossible to protect children from witnessing the violence around them, she adds. “The kids live the situation, they know the noise of the guns, that people had to run. The kids live it, they know.”

Lamba, along with Moseba, receives support from Acatba, a local organisation that provides literacy and business training as well as counselling to survivors of sexual violence. Its work is supported by Tearfund and the British government, which is matching donations to the charity’s appeal for CAR.

Elvis Guekenean Thomas, director of Acatba, says a major challenge is the lack of resources available, especially for supporting survivors of rape, who are already hard to reach due to entrenched stigma associated with sexual violence. “Some [survivors] are able to talk about what’s happened to them and to try to get access to help but others no, so we are sending out community networks to [find] victims who are hiding themselves in their houses,” he says, “A very little minority get help.”

The UN humanitarian appeal for CAR has received only about a third of the $497m required. An appeal to assist people forced to flee their homes has been less than 10% funded.The worst of the fighting in the capital is over but, for Moseba, life is anything but stable. “It’s very difficult,” she says. “I am afraid I am going to be evicted from my house and my children don’t go to school.

“Before the crisis I used to sell things, but now I have lost everything and I don’t have enough money to start another activity … Because I am an orphan and I have no one to help me, it is very difficult. The future is very dark now.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion