From cities to the countryside, Africa has undergone a dramatic transformation in living conditions over the past 15 years, according to a new study.

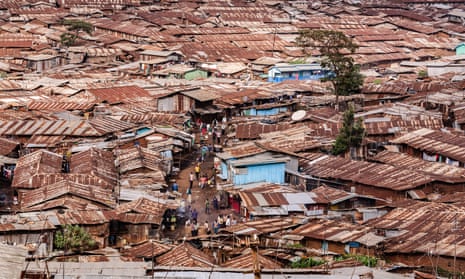

But the research, based on state of the art mapping and published in science journal Nature, also found that almost half of the the urban population – 53 million people across the countries analysed – were living in slum conditions.

Led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the study offers the first detailed estimate of housing quality in sub-Saharan Africa.

Using the most recent data available from 31 countries, researchers found housing had improved across several measures over a 15-year period. Sufficient living area, improved water and sanitation and the durability of construction were found across 23% of houses in 2015, up from 11% in 2000.

The study’s senior author, Dr Samir Bhatt from Imperial College London, said: “Our study demonstrates that people are widely investing in their homes, but there is also an urgent need for governments to help improve water and sanitation infrastructure.

“We saw a doubling in the number of people living in an improved house. This parallels the success stories we are seeing in terms of Africa’s development. It is supported by a wide variety of other studies that show that when people get sufficient income, one of the things they do is invest in their homes.”

Bhatt said the improvement will have a “huge impact” on people’s health and susceptibility to disease.

“You can give someone a mosquito net with insecticide, but having a window you can close makes a huge difference,” he said.

The study found the need for adequate housing to be “particularly acute” in Africa, since the continent has the fastest growing population in the world, predicted to rise from 1.2 billion people in 2015 to 2.5 billion people by 2050.

The improvement was highest in Botswana, Gabon and Zimbabwe. South Sudan, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were among countries where progress was less marked.

The researchers found that improved housing may be linked to economic development. Improved housing was 80% more likely among more educated households and twice as likely in the wealthiest households, compared with the least educated and poorest families.

The new data could guide interventions to achieve universal access to safe and affordable housing and to upgrade slums by 2030, one of the UN’s sustainable development goals.

Dr Lucy Tusting, who conducted the work while at the malaria atlas project, University of Oxford, said: “Adequate housing is a human right. Remarkable development is occurring across the continent but until now this trend this had not been measured on a large scale.”

The UN definition of a slum household is one that does not protect against extreme weather, has more than three people to a room, lacks access to safe water and adequate sanitation, and has no security of tenure.

The researchers, who examined 600,000 households using an innovative technique that allowed the prevalence of different house types to be mapped across the continent, defined housing as “improved” if it had the first four conditions, but did not look at security of tenure.