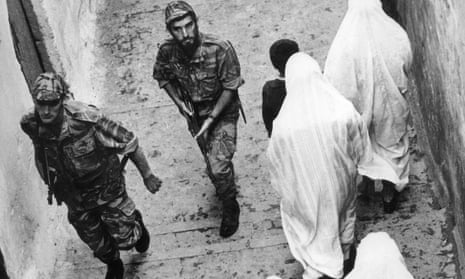

More than half a century since it was released – and promptly banned by French authorities – The Battle of Algiers, depicting the bloody struggle for Algeria’s independence from France in 1962, still has the power to shock.

On Friday night, the black-and-white, 1966 film relating Algerian anti-colonial guerrilla warfare and its brutal repression by the French military was screened in Paris. London-based musical activists Asian Dub Foundation (ADF) performed a live soundtrack.

The ciné-concert, organised months ago, had become suddenly and unexpectedly topical with Algerians in Paris, like their compatriots back home, calling for regime change following the resignation of longstanding President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, 82, last week. As the credits rolled and the reverberations from ADF’s powerful interpretation, performed alongside the original Ennio Morricone score, faded in the packed auditorium at the History of Immigration Museum, a line from the film echoed on.

“It’s only after we have succeeded that the real difficulties begin,” says Yacef Saâdi, a Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) leader who plays himself in the Gillo Pontecorvo film. Algerians have now succeeded in forcing Bouteflika out after 20 years, but now, say many, comes the difficult part: fulfilling their real and urgent desire for peaceful but total regime change.

What happens in Algeria still casts a long and sombre shadow over France, whose 132-year colonial rule over the north African nation became a form of apartheid, with one million colonialists of French origin – so-called pieds noirs – dominating nine million Algerians.

Today there are an estimated four million people of Algerian origin in France – its largest migrant community. And as the streets of Algiers have erupted in calls for an oppressive regime to tumble, so too have the streets of Paris.

“The demonstrations in Paris are very much in tune with demonstrations in Algeria. It’s all very peaceful. They want to avoid conflict and violence, but to bring about some kind of peaceful transition where Bouteflika goes but the system isn’t simply rehashed,” said Martin Evans, a specialist in Algerian history at the University of Sussex.

With Algeria’s ethnic and cultural diversity, it was perhaps inevitable that some of the historic tensions that have existed for decades between different groups would resurface at a time of heightened emotion: in particular, tensions between Algeria’s Arabs and Berbers – known as Amazigh in the indigenous language.

Berbers make up about 30% of Algeria’s population and while a minority follow the Ibadi school of Islam, most, like their Arab compatriots, are Sunni Muslims. For centuries they lived peacefully together, but during colonial rule the French stoked the cultural and linguistic differences as a divide-and-rule tactic. In recent years there have been sporadic outbreaks of violence and killings, as Arabs migrated to traditionally Berber areas competing for jobs, land and homes and leaving Berbers claiming they were being discriminated against in an attempt by the government to “Arabise” the country.

Evans said he had been surprised to see Amazigh flags at recent demonstrations he attended in Paris. “I hear people saying the Arab-Berber issue isn’t a problem, but when I spoke to demonstrators there was certainly some tension between the two groups, so it’s evident the issue isn’t just colonial and will have to be dealt with,” he added.

Omar Kezouit, whose association Agir pour le Changement et la Démocratie en Algérie (Act for Change and Democracy in Algeria), has organised demonstrations, said the ripples of events unfolding in Algeria were felt keenly in France, and that but insisted the diaspora had put aside its divisions. He told the Observer: “Algerians are united by the fact they have no hope in the current regime and desperately want change. What do we want? We want a country that gives us proper leaders, hopes and futures, and above all freedom. What we don’t want is to be tricked.

Algerians are also profoundly scarred by the country’s experiment with Islamism that led to what they call the “Black Decade”, the 1992-2002 civil war in which between 50,000 and 150,000 died (the figures are disputed). But Kezouit and Evans dismissed fears that the current unrest could encourage a resurgence of Islamism.

Evans said: “Algerians will tell you Islamism is something that happened in their country and they definitely don’t want to go there again.”

Azouz Kamel, a freelance Algerian journalist working in Paris, who was at the ADF ciné-concert, agreed. “The press in France is making a big thing about the problem of Islamism in Algeria, but it has nothing to do with what is happening. People don’t want Islamists. We have turned the page on that,” he said.

Certainly, what unites Algerians in France is fear that Bouteflika’s departure will change nothing. Kamel said: “Right now I’m not at all happy. We’ve gone from a clannish, family dictatorship to a military dictatorship.

“We don’t want the job half done. We want a radical change to the whole system. I came to France 20 years ago when Bouteflika took power and Algeria was rich. He has brought the country to its knees with widespread corruption. His clan, friends and supporters have got rich. The poor have got poorer.”

Kezouit added: “Nobody wants the army or old regime. We fear they will sacrifice some people to make out they’ve listened to the people, then try to carry on as before, but we will engage with them peacefully.

“Algerians have paid heavily for years of conflict. We remember this well. The wounds are still open. So it’s important that, while we need to be victorious, it must be peacefully.

“But everyone who represents or is part of the regime must go. We say, you got rid of Bouteflika. Great. Now go home. All of you. Algerian people will not be satisfied until they have that change.”

At the ciné-concert, part of the Paris-Londres Music Migrations exhibition, ADF’s interpretation of The Battle of Algiers was cheered and applauded. When the film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1966, the French delegation walked out. It was so politically sensitive in France that even after the brief ban was lifted it was not screened there until 1971.

Steve Savale, ADF’s lead guitarist, said he hoped Algerians in the audience would feel the group had interpreted a piece of their history “respectfully” and in doing so had “kept the struggle alive”. Bass player Aniruddha Das, aka Dr Das, said the film had resonated with members of the multicultural British group: “Like Algerian people we all have the same colonial experience. We’re all in Europe because Britain or France occupied, exploited and sometimes engaged in genocide in our respective places and we can relate to that.”