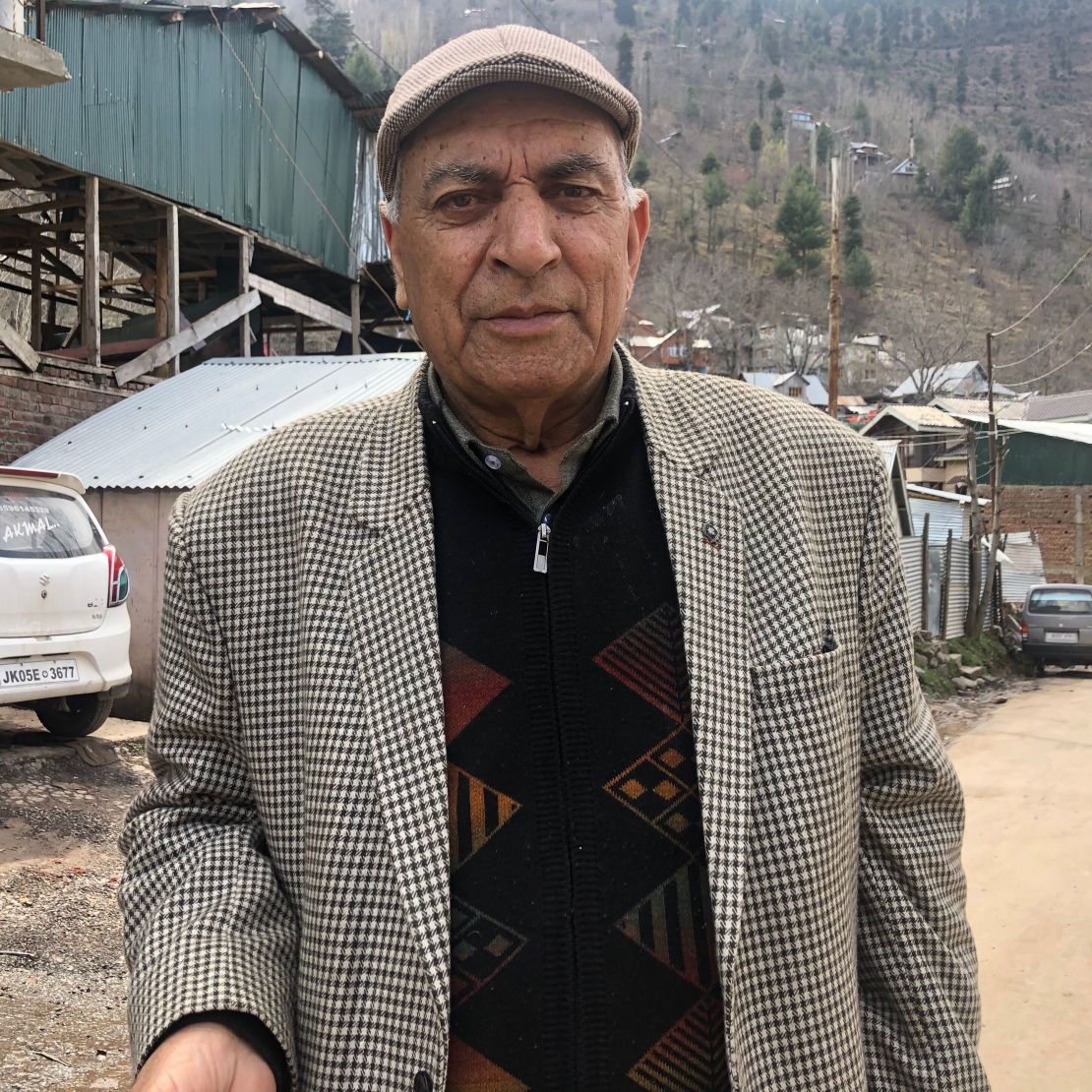

Kashmir resident Gulam Rasul has seen it all: Two wars between India and Pakistan which were sparked by the disputed region as well as dozens of other armed conflicts.

Over the years, he’s given up dreaming for peace. “If you can’t give us peace, give us the bunkers at least,” says the 76-year-old, who lives in the town of Uri in Indian-controlled Kashmir.

Uri sits perilously close to the Line of Control, the de facto border that divides Kashmir between India and Pakistan. As a result, locals say, the town and surrounding villages are frequently caught in the crossfire when the two sides fire shells at each other – a common problem that’s worsened in the aftermath of an aerial dogfight in late February.

“We want the bunkers so that we have a place to hide during intense shelling. We don’t have anywhere to go and no means to protect ourselves. This is injustice,” Rasul says.

India’s main political parties, according to Rasul, are ignoring the area’s real problem – unemployment – and instead are just using the Kashmir issue for political gain, especially in the run-up to a nationwide election which got underway earlier this week.

Apart from the regular cross-border shelling, there are constant clashes between local militant groups and Indian troops and police. The relentless cycle of violence has a severe impact on daily lives, with the cost of essential supplies rocketing during flare-ups.

“Living here is expensive. Dying here is extremely cheap,” Rasul says.

Local political activist Nadim Abbasi organizes protests aimed at bringing these issues to light. On his mobile, he shows photos of Reyaz Ahmad, who was critically injured when a shell hit his house in a border village near Uri in early March. The 32-year-old had to have his legs amputated and died in hospital two weeks later.

“A bunker could have saved his life,” Abbasi says.

For vegetable seller Nadim Khan, 75, the cross-border shelling is nothing out of the ordinary.

“Coming here must be exotic for foreign journalists like you, right?” Khan says mockingly.

“This is an everyday reality for us. I grew up seeing this, and I’ll die seeing this. The situation will be the same for generations to come. Nothing will change. I don’t worry about it anymore. I will die the day and the way Allah wishes,” Khan adds.

India and Pakistan each control part of mainly Muslim Kashmir but each claim the region in its entirety. A revolt since 1989 in the Indian section, by groups seeking independence or union with Pakistan, has claimed thousands of lives.

The impact of the conflict isn’t confined to the border area – it reverberates across Kashmir including Srinagar, the main city in the Indian-controlled section.

When CNN visited in March, the city center resembled a ghost town. Local separatist groups had called for a shutdown after a teacher arrested for alleged terror links died in police custody.

Schools and businesses were closed, and streets were deserted except for police or troops on every corner – not an unusual sight for Srinagar residents.

For visitors, the city is one of juxtaposing realities: A mesmerizing landscape, with a backdrop of tall mountains, in what is one of the most heavily militarized places on Earth.

Last year was the bloodiest in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir in a decade: 238 militants died while 86 police or troops and 37 civilians lost their lives. 2017 was hardly less deadly.

The death in 2016 of Burhan Wani, an influential young militant leader, sparked a wave of unrest that has claimed scores of civilian lives and left thousands injured. Many were partially or fully blinded by the use of pellet guns, a controversial move by Indian security forces to quell protests.

The separatist insurgency and the frequent quarrels between India and Pakistan have hit the local tourism industry hard. Some 12.5 million tourists visited Jammu and Kashmir in 2012, a figure which dropped to 7.3 million in 2017.

Tourists used to start flocking to the region in early spring. Not anymore. The houseboats on the idyllic Dal Lake – one of the most popular destinations in Srinagar – sit empty and dozens of boatmen on the shores wait desperately for customers.

Hotel taxi driver Mohammad Shafi complains that he didn’t have a single customer for a couple of weeks in early March, when India and Pakistan were on the brink of war.

“The tulip gardens of Srinagar are expected to be in full bloom in a few weeks…Inshallah (God willing), the tourists will start coming again soon,” he says hopefully.