In 50 years, the region near where I grew up, Cameron Parish in south-west Louisiana, will likely be no more. Or rather, it will exist, but it may be underwater, according to the newly published calculations of the Louisiana government. Coastal land loss is on the upswing, and with each hurricane that sweeps over the region, the timeline is picking up speed.

As a result, Cameron, the principal town in this 6,800-person parish (as counties are called in Louisiana), could be the first town in the US to be fully submerged by rising sea levels and flooding. So it’s here one would expect to feel the greatest sense of alarm over climate change and its consequences.

Instead, Cameron has earned a different kind of fame: it’s the county that, percentage-wise, voted more in favor of Trump than all but two other counties in the US in last year’s election. (Nearly 90% of registered voters did.)

Why would some of the people most vulnerable to climate change vote for a politician skeptical of climate change’s existence? Why would people in Cameron Parish support policies that could ruin them?

To get to the root of this question, I slipped my tennis shoes into knee-high marsh waders, navigated the ropes on a rusty shrimp boat, and ate mountains of fried seafood. I spoke to people living different and yet parallel lives in Cameron Parish, where timelines are defined as pre-storm or post-storm, and where people kindly addressed me as Miss Shannon.

In rocking chairs and over lunch specials, I asked them about their seemingly contradictory views. I asked them why they voted for Donald Trump. And I asked them how they felt about being the proud residents of what may be America’s first drowning town.

Tressie Smith: ‘If a hurricane comes, I’m screwed’

Tressie Smith is a 44-year-old mother of two and a business owner – her seafood restaurant is the most popular lunch spot in town.

That popularity is aided by the fact that her would-be competition was all destroyed in hurricanes Rita (2005) and Ike (2008). The population of Cameron dropped a stunning 79% between 2000 and 2010. When the hurricanes hit, Smith was working for a cafe down the road. When it closed after the storms, Smith saw an opening. She bought a barber shop, tacked up naval-themed decorations and named her new business Anchors Up Grill, a wry nod to the local conditions. Her special is the “dynamite shrimp poboy”, a sandwich with jumbo shrimp grilled in a spicy sauce and covered in melted cheese and bacon, for $11.

“Oh yeah, I’m concerned,” Smith says when asked about the future. “And the bad thing is they won’t give me any hurricane insurance. They said my building don’t qualify.”

Her structure, with its glass and metal garage and creaky wooden trailer steps, stands out among the remaining buildings on the street, which are mostly bunker-like big cement city offices. If another storm hit, Anchors Up looks like it’d be the first to go. “They did insure me the first year we were open, but then, for no reason, they wouldn’t renew it,” she recalls. “But this is all I can do, because I had to mortgage my house and my land to get this. Because of the rules and regulations, it costs so much to live here.”

Many locals in Cameron repeat this phrase – “rules and regulations”. They’re referring to the strict construction rules placed on residents who wanted to return to Cameron and rebuild after Rita and Ike hit the town. As a result, all structures needed to be raised in order to qualify for hurricane insurance. The result is a humble town whose homes appear strangely grandiose: single-story modest brick houses now rest on top of large, grassy man-made hills, a kind of south Louisiana castle.

For 10 years, Smith was a truck driver, which gave her a particular vantage point from which to observe the coast. “I think the coast is disappearing, I really do. Because I traveled this road so much, driving for the oil fields. By the way it looks, it looks like the water is getting closer and closer.”

But Smith stops short of offering an explanation. “I really don’t know what is causing it, I don’t know what you’d call it – erosion? I guess it’s probably caused by climate change, but I don’t really believe in the concept.” She pauses to sip her Coke, and reconsiders. She looks east down the road, where an $11bn- liquefied natural gas plant is slated to be constructed, once federal approval comes through. “But why would they be spending millions of dollars on those liquefied natural gas plants if the coast’s going to disappear? And they probably know a lot more than me.”

As for her politics, Smith thinks Cameron’s residents voted for Trump because “we think he could help the oil field out, and hopefully stop the imported seafood from coming into our country so our people can make a living,” she says.

Smith, like most of the residents of Cameron, has been highly dependent on state and federal assistance programs to recover after the storms. But what if, in Trump’s push to shrink the size of the government, recovery programs are cut?

“We’d be screwed,” she says frankly. “But that doesn’t change my opinion about Trump,” she quickly adds. “Outsiders think that everybody is just looking for a handout down here, but there is hard-working people that live here. There are just not many jobs right now, especially if all you know is commercial fishing. Even if Trump cuts those programs that helped us, we gonna make it one way or another here, with or without help. Down here we survive.”

Brandon Vail: ‘You can’t wait around for some bureaucrat to tell you what you can and can’t do’

Standing in green wading boots in shin-high water about 40 miles north of the Anchors Up Grill, Brandon Vail wipes the nitrogen pellets off of the inside of his glasses. A fertilizer plane has just passed over his rice field.

Vail is a young, highly educated self-employed rice farmer who makes about $35,000 a year from farming. He works on 4,500 acres of land – corn, crawfish, cattle, hay, soy beans and rice – which he leases from 22 different landowners. But the arable land around where Vail farms is disappearing, as development sprawls and coastal loss creeps northward.

“With the ground losses we have here, it doesn’t really pay to be really big for us. I do better to be diversified. I been losing ground to residential and commercial development, and also to mitigation land to make room for that. So over the last four years, I’ve lost about 1,000 acres. Some people have lost more.”

He’s not optimistic about the future of farming. “This year is my 19th crop. I probably picked a poor career choice because I can see the writing on the wall. If I had kids I wouldn’t want them doing what I’m doing in this area. I don’t think farming will be a viable industry in this area 50 years from now. I may be wrong. I hope I’m wrong.”

Vail is a registered Republican, and he gets heated when he thinks about how his fellow Trump voters are perceived from the outside.

“Everyone thinks just because you’re from the south you’re a Confederate flag-waving drunk idiot. We’re not all like that. Some of us are educated. We just see things different from you.” He added: “My parents busted their ass and cut corners for me to go to private school. My sister is a complete Democrat. We’re Catholic. But I’m looked at like some kind of racist slaveholder. I’m lumped into that category. But we don’t fit.”

Vail says he’s pleased with the drawdown on environmental restrictions that Trump has instituted since taking office.

“When he took office he stopped the EPA’s Waters of the US rule, where anything that would flow into a navigable tributary would have had jurisdiction under the EPA. Well, navigable tributaries go through half the land I farm. So you’re saying a ditch I put in my field to drain the water off, then that the land comes under your jurisdiction? You can tell me when I can go into it, and what I can use as fertilizer?”

He shakes his head in disgust. “Residents can go buy RoundUp, can send out their detergents and soaps and all this kind of runoff into downstream water, but then they want to blame the farmers?”

Vail adds: “There’s not a farmer on earth that is going to ruin soil or water. We learn best management practices, and most of us will use those practices because it increases the bottom line. You can’t wait around for some bureaucrat to tell you what you can and can’t do.”

Benny Welch: ‘If you go by what the real scientists say, there’s no proof’

“I’m gonna let you in on a little secret,” Mr Benny says, as he leans close enough that his worn white baseball cap shades the afternoon sun on my face. “I’m the luckiest man in the world.”

Seventysomething Benny Welch lives across from the oceanfront marsh in Cameron Parish, just behind a big oak tree, whose limbs he clung to through the night in 1957 when Hurricane Audrey hit, sweeping his family out of their home and him – fortuitously – into a wishbone-shaped crevice of branches, the only thing left standing when it was all over.

Mr Benny – as everyone refers to him here – spends his days strolling through a garage packed with boxes overflowing with severed alligator parts.

He and his family make their money hunting alligators, and then selling the otherwise discardable pieces of the alligator bodies – the styrofoam-like handles of perforated jawbone, the scaly claws with ladylike fingernails, the phallic-shaped teeth stained brown with age. The Welch family have done well for themselves thanks to a number of contracts with gas stations around the south, whose clients impulse purchase the alligator-tooth necklaces as they pay for their Big Gulps. He shows me one of the most popular pieces: an alligator tooth surrounded by rectangular beads stamped with the Confederate flag.

But business wasn’t always so good. The double-hit of hurricanes in 2005 and 2008 “turned the marshes upside down”, he recalls. “We didn’t know what what to do, there was no alligator eggs for three years.”

Mr Benny’s son lets me know that their alligator hunting business has brought in a high-end clientele. He brings out a photo of a grinning Donald Trump Jr taken during an alligator hunting trip. That personal connection has helped inform Mr Benny’s politics. “I’m Donald Trump all the way,” he says with a smile.

Even though Mr Benny’s family has been directly impacted by hurricanes, and even though the state mapping agency indicates that his home will be submerged within 50 years due to coastal land loss, Mr Benny isn’t buying it.

“I don’t believe it,” he says, shaking his head. “I don’t believe that the tide is gonna rise 10 feet and that the Ice Age is coming and stuff like that.” Like many of the residents here in Cameron, Mr Benny sees time on a longer horizon than others might. “I been here 75 years, you understand?,” he reminds me with gentle force. “And I’ve lived on the water and guess what? The tides still come up almost the same way, and there is no flooding. And today our front marshes aren’t underwater.”

“If you go by what the real scientists say, there’s no proof. In the last 10 years the average temperature of the world hasn’t even risen a half degree. And if you listen to everyone talking it, it’s up five or 10 degrees. And it’s not true! It’s a political thing. How much money has Al Gore made off global warming?,” he laughs, shaking his head with a cackle. “It ain’t happened yet!”

Bronwen Theriot: ‘I think the data is incomplete’

Bronwen Theriot is the 36-year-old science teacher at South Cameron High School. She’s also a member of a group colloquially called the “die-hards”: residents who had their homes destroyed by Hurricane Rita in 2005, managed to rebuild, and then had their new homes destroyed again in 2008 by Hurricane Ike. And still, she made it home. “I came back every time. To the same place,” says Theriot, proudly.

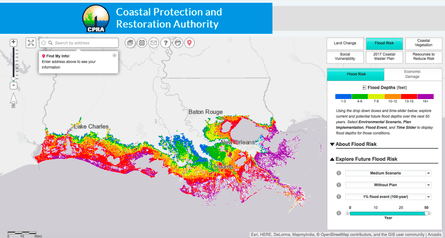

Theriot’s boyfriend works for the state, and so state policies on coastal subsidence are regular dinner conversation for the couple and their kids. “I’ve looked at those maps a million times,” she says, referring to the maps recently published by the state of Louisiana that show Cameron 50 years from today in the “red zone” – underwater. “I’ve looked at the aerial photos. I see how if we don’t do something to protect our coast we will have no coast to protect,” she says, matter-of-factly. “And it is evident if you take a ride around here.”

To the right of her home are a line of weed-bedraggled cement slabs, where her neighbors once lived; empty plots left by those driven away by the uninhabitability of this coast.

“From a scientific perspective,” she says, putting on her high school science teacher hat, “the map is showing you – look, this is going to happen. Compared to other places where they have stopped the erosion versus here where they haven’t, it’s clear that not enough is getting done.

“But I don’t know what is causing the coastal depletion,” she says. “When it comes to depletion and subsidence, I feel like there are so many items it could be attributed to, and perhaps it is not one individual thing, but a lot of things adding up.

“Do I think it is climate change? That’s hard,” she says, smiling. Theriot seems caught between her job as a science educator and her life as a longtime Cameron resident, tasked with teaching about the environment in a fiercely red town.

“From a scientific perspective ... data is manipulated all the time. So whoever is interpreting the data, as much as you try to not have a bias, you could still have a bias. Of course, I am going to be more proactive about coastal restoration and protections because it is directly affecting me, so for me, looking at the data, I am very very worried.” She relents: “But I think the data is incomplete. And I am still not sure about climate change. I am still researching it. I feel like I don’t have enough good sources to say yes or no on if climate change is a real thing.”

Now, from her elevated balcony overlooking the old slabs, she takes a clearer position. “I’m a big proponent of the oil industry, because that’s how my family and my community made a lot of its money. So that is my livelihood. So it is hard for me to point that finger.”

Leo Adley Dyson, Sr: ‘If I thought global warming was real, I’d be the first to admit it’

The Louisiana shrimping season just opened this week, and as a lifelong shrimper and the owner of a couple boats and a dock, today should be a busy day for Leo Dyson, not a slow one. But the wind’s been blowing too hard to take out the boats, and so here he sits, perched on a pile of barnacle-crusted wood pallets.

Dyson cares most about shrimp. “In these countries like China and everything, they work under communism where the government owns everything – the boats, the factories. In China, they raise their shrimp in sewage ponds they load with antibiotics, and that can cause cancer. We are one of the few countries that will even accept shrimp from China, and it doesn’t make sense that the FDA even allows that. But we gotta produce shrimp for the same price as them under free enterprise.”

“So I think Trump will help this. I think he will make changes to the FDA and import tariffs and all that. I think he will make a more even playing field where everybody will still be able to make a living. So I voted for him because I thought he was the best man for the job.”

Dyson is not particularly concerned about the forecasts that show the coast disappearing over the coming decades. He thinks global warming is a gossipy scam.

“Too bad you’re not writing for the National Enquirer,” he teases, “because then you could say ‘fisherman sleeps with alien and causes global warming!’

“The fact is I’m 68. I’ve seen cold weather and I’ve seen hot weather. And you know the earth’s been through some ice ages. And when the ice ages was over, did they think it was global warming? A planet that doesn’t change becomes a barren waste, so that’s why it’s changing.”

Instead, Dyson says that what worries him most are the environmental regulations ostensibly intended to save the coast. “The laws are already there to protect the coast. And I understand Trump is not 100% environmentalist. But I think it’s a good thing to get the government out of our lives. I don’t want any more environmental regulations. I don’t want any more fishing laws. And I don’t want a lot of restrictions where people can’t make a living.”

Dyson says hurricanes aren’t all bad news in his line of work. “The wetland restoration is doing more to harm the ecosystem than if they left it alone. After [hurricanes] Rita and Ike we caught a lot of shrimp, because the levees were washed away and nature worked the way it was intended to, where man didn’t mess with it. These structures – the levees and all – are making it get worse every year. So for me having a hurricane would be good for business – for a little while.

“If I thought global warming was real, I’d be the first to admit it,” he says, looking out across the rough water. “Because I’d be the first to see it. I’m here on the water after all. I could see how in 3,000 years we could be underwater, because I mean who knows, but in 50? I don’t think so. I was told that 50 years ago. Things don’t change much here.”

- This article was amended on 28 August 2017. A previous version incorrectly identified Cameron Parish as the US county with the highest percentage of Trump voters in the 2016 presidential election.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion