The residents of Lucky House in Hong Kong are anything but fortunate. They are some of the poorest people in the most expensive city in the world.

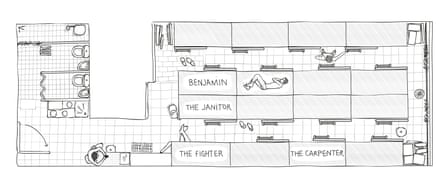

In one of its 46 sq metre (500 sq ft) apartments, 30 residents live in purpose-built plywood bunk beds each with its own sliding door, colloquially known as coffins. Two rows of bunks, 16 bunks in each row – still space for two more people.

The residents are retirees, working poor, drug addicts and people with mental illnesses, mostly those unable to keep pace with the spiralling cost of housing in Hong Kong.

In many ways their home feels like a railroad sleeper car, but even more cramped and uncomfortable, and with none of the charm or romanticism that comes with train travel.

For a week I lived at Lucky House, crammed in a stuffy bunk teeming with bed bugs at night, my days spent lazing around with not much to do besides talk to the other residents, stare at my mobile phone and sleep.

Bed bugs, meth and no natural light

When I enter my coffin for the first time, I immediately notice the strong musty smell. I imagine the other residents in their bunks, each one roughly 60cm (two feet) wide and 170cm (5 ft 7 in) long, with only enough space to sit up. Living in such a confining space takes a mental toll but my week pales in comparison to the other residents who have been living there for months, sometimes years.

At night I can hear everything happening around me: every punch, kick and scream from my neighbour’s kung fu movie; the smacking of lips eating barbecue meat with rice; a brief argument over who will use the sole shower next and, of course, a symphony of snoring.

The next morning the sound of a plastic travel alarm clock first wakes me up at 5.30am. But in my coffin, there is almost no sense of time. It could be any hour of the day, and no natural light would reach me. For that I would have to leave my bunk and walk to the sole window at the other end of the apartment.

When I finally leave my coffin around 7.:30am, one of my neighbours is already preparing his first dose of meth for the day. Hong Kong’s coffin homes have a reputation for danger and filth, sheltering convicted criminals and drug abusers, and in my short time I saw roughly a quarter of the people regularly using drugs.

But the residents of Lucky House were also some of the friendliest people I’ve met in Hong Kong, and almost instantly welcomed me, with one person in particular keen to show me the ropes of coffin living.

The Fighter

The Fighter was relatively new to Lucky House, having moved in about six months earlier. At 37 he is a bit too old to work as a low-level triad enforcer, but his arrival in the coffin home coincided with a hiatus from Hong Kong’s world of organised crime.

“This isn’t my real home, my home is the apartment I shared with my wife and daughter,” he says. “But this place is cleaner than most coffin homes, and everyone is very friendly.”

The Fighter dodges questions about his family, who he says live just four subway stops away, a minor commute if he had the money to afford the ticket. He does not carry a photo of his eight-year-old daughter and says he only sees her twice a month at most.

The Fighter is the only person I meet in Lucky House who is not rail thin, and his portly belly is often on display as he walks between beds shirtless. When he does wear a shirt, it is usually a Barcelona replica with Lionel Messi’s name on the back.

As I quickly learn, his two favourite topics of conversation are football and pornography, and after a few minutes of talking the Fighter has become restless and suggests: “Let’s go walk around and look at girls.”

As we step out into a sticky Hong Kong evening, the Fighter begins to tell me his story.

He was born on Hong Kong island in 1980, just as the then British colony’s economy was about to take off. But the Fighter would never benefit from the city’s newfound wealth. He started working at a triad-run auto repair shop in Wan Chai, a neighbourhood known for its red-light district, while he was still a teenager. He was adept at street brawls, especially when armed with his weapon of choice: a metal pipe.

The Fighter says he never killed anyone. But the toll of conflict is clearly visible; he has a large scar on his left shoulder and it looks like more than a few bones have been removed.

When I ask him about the scars, the Fighter says it is a football injury, but his face gives away his lie. He is embarrassed and I learn that the Fighter hates to appear weak.

He also never answers when I ask him about his many missing teeth. Only two in the front remain.

As I continue my walk with the Fighter, the density of the city comes into sharp focus. Just a few blocks away from Lucky House, scantily clad sex workers stand in doorways, beckoning pedestrians to join them upstairs. The Fighter says he visits a sex worker about once a month, at a cost of HK$200 (£20).

“Technology has gotten so good, I don’t need to go often,” he says.

Eventually we arrive at the Langham Place shopping mall. The strangeness of this place sets in as we ride the escalators to the top, passing a sign at a Calvin Klein store advertising special discounts if you spend the equivalent of double my coffin’s monthly rent.

The Fighter looks at the price of everything, and like clockwork makes the same comment about each item: “Fuck, this is really expensive!”

“My brother is very rich, he spends HK$10,000 a month just on his girlfriend,” the Fighter tells me. But he hasn’t spoken to his brother in years.

On our way back to Lucky House, the Fighter grabs me as he turns quickly down a sidestreet.

“I just saw my triad boss,” he says, visibly shaken. “I’ll have a lot of trouble if he sees me.”

The Fighter is vague with his explanations of the near miss, but he wants to quit his former life of crime; his time in the coffin home is an attempt to lay low as he waits for heads to cool.

When we finally get back to Lucky House, the Fighter seems relieved. He collapses into his bunk and starts watching television on his mobile phone. The walk was the farthest he has been from Lucky House since he moved in.

Glamour, luxury and growing poverty

Coffin homes started in the late 1950s and were mainly occupied by new migrants from China as part of employer-provided housing. Originally they were metal bunk beds that were then wrapped in a chicken-wire type of fencing, and a few of the old-style caged homes still exist.

Lucky House is just a 15-minute walk from one of Hong Kong’s glitziest shopping districts. Hop on the subway at the corner and 20 minutes later you would emerge among the towering skyscrapers of the city’s financial district.

Away from the glamour at the other end of the economic spectrum, many pay for their coffins with a roughly HK$1,800 (£180) a month government subsidy. But social benefits alone are not enough. The monthly rent for one bunk ranges from HK$1,800 to as much as HK$2,500, according to the Society for Community Organisation (Soco), an NGO that provides assistance to Hong Kong’s poor.

My bottom bunk bed space cost HK$2,100 a month, although the top bunk was slightly cheaper. For that amount I was allotted about 1.1 sq metres (12 sq feet) of personal space.

While not a problem for any of my neighbours in Lucky House, the coffins are only 170cm (5 ft 7 in) long, quite uncomfortable for my modest height of 178cm (5 ft 10 in).

Hong Kong is by far the most expensive housing market in the world. The average person would need to save more than 18 years of pre-tax salary, spending that money on nothing else, in order to afford a home. Nearly one in seven Hong Kongers lives in poverty, according to the latest government report, the highest level in six years.

Under chief executive Leung Chun-ying, who left office in June, programs to alleviate the skyrocketing cost of housing have been called “a failure, if not a total flop”. Despite pledging to make housing the centrepiece of his administration, Leung built only half the amount of public flats he promised to deliver.

“The housing situation is getting worse,” says Angela Lui, a community organiser at Soco for the past seven years. “In terms of rental prices, quality of the apartments and waiting time for public housing, all of these things have gotten worse.”

The average wait time for public housing is more than four years and eight months, increasing by a full year compared with 2016. More than 100,000 families are vying for coveted spots. But the government’s calculation excludes several types of people, including single people under 65, who can be forced to wait more than a decade.

As wait times for government housing increase, “it means these people are stuck in a poor living environment for a longer amount of time”, Lui says. She travels between dozens of coffin apartments, passing out donated goods, helping residents apply for government benefits and undertaking the maddening task of trying to map the transient community.

There are about 200,000 people living in some form of subdivided apartment in Hong Kong, including coffin homes, and 18% are younger than 15, according to a government report released last year. But Soco say the number is likely higher, as many illegal apartments were left uncounted.

Dread sets in

Towards the middle of my stay in Lucky House, I start to dread returning to the claustrophobic space. On my way home at night I duck into a McDonald’s, located in a basement, to cool off and collect my thoughts before going back to the coffin.

As I walk to the restaurant’s back room with a milkshake, every booth is occupied by sleeping homeless people, McRefugees as they are known, a reminder that a coffin may not be as far as one can fall.

Many blame the government and property tycoons for the current state of affairs. The Hong Kong government posted a HK$92bn (£9.2bn) surplus last year, and has fiscal reserves worth HK$860bn (£85.6bn). Despite that wealth, it remains one of the most unequal cities in the world, behind only New York, and the poorest 10% earn £260 a month on average, barely enough for rent in a coffin home.

Members of the city’s pro-democracy camp are disappointed with how officials are using those funds.

“The government is not putting enough effort into helping less fortunate citizens access affordable housing,” says Nathan Law, a lawmaker and member of the legislature’s housing panel before he was disqualified by a court in July. “The social housing supply is definitely not enough since the government is not willing to challenge special interests groups, like property developers or foreign investors.”

Law blames the sharp increase on property prices on outside money, much of it coming from mainland Chinese investors. Hong Kong officials have imposed taxes on home purchases for years in an effort to tamp down speculation, but property remains out of reach for many.

The Janitor

One particularly hot afternoon I escape to the open-air hallway just outside the door to the apartment. That’s where I meet the Janitor, smoking a cigarette as he leans against the railing overlooking a grimy back alley.

The Janitor can barely remember a time before living in Lucky House. He managed to move out a few times; one job provided dormitory housing but he was forced to return when he injured his leg and could no longer work.

“I’m injured and I have a lot of health problems so I can’t work anymore, but I’m too old anyway,” he tells me. Along with exactly how long he has lived at Lucky House, the Janitor also cannot remember his precise age, saying only he’s “over 60”.

He walks with a cane now and his smoking habit means he is unable to travel far from his oxygen concentrator, which sits just outside his coffin with a thin plastic tube snaking into a crack in the plywood door.

He rarely has a need to travel far. His relatives are all dead and he has no one to visit. But he attempts to keep himself busy closer to home.

The residents of Lucky House light incense for the God of the Soil and the Ground twice a day, and the Janitor often tends to this task. The deity is worshipped for wealth and fortune, but so far has bestowed neither on the people living in coffins.

Occasionally, food delivered by a local charity ends up as an offering to the god at a small shrine, no more than 60cm (two feet) tall and built into the wall beside the door.

The Janitor points to it proudly and says: “There are shrines like these all over the world, there’s one in Chinatown in New York.”

He has never been to New York, or ever left Hong Kong, but he is proud that a piece of his culture can be found in nearly every corner of the globe.

The Janitor and I share a wall, a thin half-inch piece of plywood painted mustard yellow that does little to block the sound of the films he watches on a portable DVD player and his frequent coughing.

The plight of Hong Kong’s coffin dwellers is well known throughout the city. The tight living conditions have become so infamous, one hostel styled its dormitory as a sort of hip hybrid of coffin homes with modern details.

The hostel bills itself as “authentically HK”, which strikes me as insensitive, as no one who has spent a night in a coffin home would ever think there is anything trendy about how the poorest live.

But the hostel’s existence speaks to the complacency that has developed, with many Hong Kong residents convinced the city’s problems are unsolvable. In recent years the number of people living in coffin homes has declined, according to Soco, although there is no sign they will disappear any time soon.

“The number of caged homes is declining for sure, but we don’t want society to think people living in subdivided units is acceptable, that it’s somehow a step up, because it’s not,” Lui, the community organiser, says. “If you look at Hong Kong’s economic and financial situation, you can’t say it’s all right we have thousands of families living in such poor living environments.”

As I became more accustomed to coffin life, my neighbours became more comfortable having a foreigner in their midst.

The Carpenter, and goodbye to the coffins

As I sit with the door to my coffin open, a small man just over 150cm (five feet) hovers over me with a beaming smile. He speaks to me in English and is surprisingly fluent.

The 67-year-old is retired, not by choice, from a life as a carpenter. He belongs to a generation educated under the British and many elderly Hong Kongers speak better English than students 50 years their junior.

The Carpenter is another recent arrival in Lucky House, just 10 days before me, but only because he managed to scrape together enough money to put a roof over his head for at least a month.

“I don’t know where I’ll go at the end of the month, I haven’t been able to find work in months,” he tells me. “No one will hire an old man.”

His bunk is spartan, with just a bit of foam padding he uses as a mattress, and a faded poster of a bikini-clad woman. Before he arrived at Lucky House, the Carpenter slept in a park, but his few possessions were recently stolen and he opted for the relative safety of living in a coffin.

“The government money isn’t enough for my rent and the other things I need to pay for,” he says, stumbling over his words and seeming uncomfortable. “The money runs out, always runs out.”

The next morning I see what he means. When I go over to his bunk to talk more about what forced him to live in a wooden box, he is smoking from a small glass pipe.

The next time we talk, the Carpenter shrugs off his drug habit. He cannot remember the first time he smoked meth, but he insists the drug does not control his life. He opens a bag and offers me his glass pipe with a smile. He genuinely believes he is just being neighbourly.

I decline and we both fall silent.

My entire week in Lucky House I wondered about a certain section of wall inside my coffin, filled with dozens of dark red streaks.

On my last night there, I found what caused the strange marks after I killed a bed bug crawling next to my face. The other residents seem unfazed by the constant presence of the itchy bite marks, and everyone I ask has accepted the insects as a fact of life.

As I say goodbye to the residents of Lucky House, the Fighter is reluctant to let me leave. I spent most of my time with the jocular man, and he will not say goodbye without one last story.

He tells a fantastic tale about a day years before when he was driving in one of Hong Kong’s upscale beachside villages. He crashed into another car and the driver was his favourite actress, Karena Lam. She shrugged off the accident and gave him an autograph as gift.

As I listen to his story, it seems too perfect to be true. It makes me re-evaluate everything the Fighter has told me.

I struggle to decide what is true; the triads, the estranged family, the rich brother and a day when he owned a car.

Maybe he just wants to reinvent himself in his mind to escape the monotony of living in a wooden box, before he eventually ends up in a real coffin.

With additional reporting by Kestrel Lam