Many of the buildings that collapsed in the earthquake that killed 225 people in Mexico City last month were the subject of citizen complaints about safety, a Guardian Cities investigation can reveal.

Since 2012, the residents of Mexico City have lodged nearly 6,000 complaints about construction project violations, with no public record of how many were followed up.

Many of the buildings in question subsequently collapsed in the 19 September earthquake, which was notable for the high number of new or recently remodelled buildings that suffered surprising damage.

In 2016 alone, Mexico City residents lodged 1,271 complaints about violations of zoning or land use ordinances with the Environmental and Zoning Prosecutor’s Office (Procuraduría Ambiental y del Ordenamiento Territorial, PAOT), the city watchdog for environmental and building compliance.

More than 44 buildings were destroyed in the earthquake, and another 3,000 were evacuated, but residents and advocacy organisations say the city government did not heed the vast majority of complaints.

“I have not seen a single sanction,” says Josefina MacGregor of Suma Urbana, a group of neighbourhood associations in Mexico City. “Facing pressure from citizens, the government will sometimes say that they are going to sanction the developers [for building violations]. But it’s not true.”

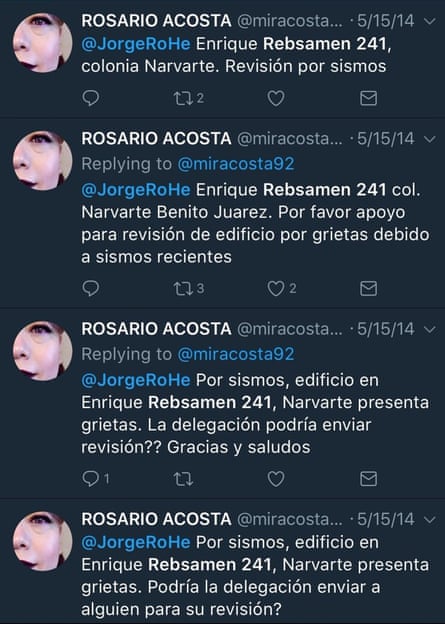

In the Narvarte neighbourhood, for example, Maria del Rosario Acosta Olivares began renting at 241 Rebsamen, a five-storey apartment building, in August 2013. After a 6.4-magnitude earthquake in May 2014, Acosta Olivares noticed numerous cracks had emerged in the concrete of her building.

“They were all over the building on the columns, and walls. And we noticed the whole building was tilting back,” Acosta Olivares told the Guardian.

She sent a series of tweets to the local government of the Benito Juárez area, asking for the authorities to inspect the building. When no one responded, she called the government offices.

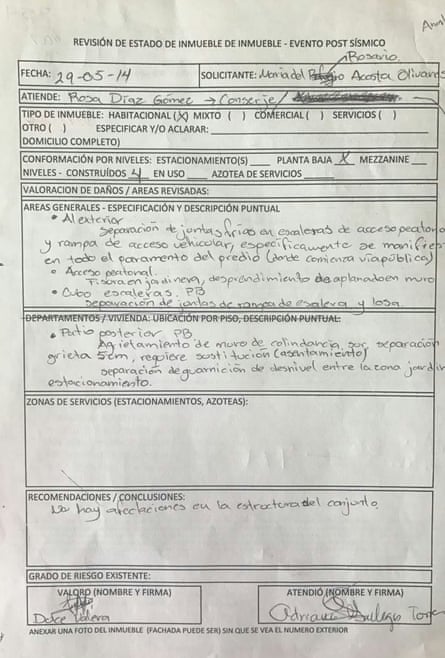

The civil protection office agreed to inspect the building, but came while she was at work. “[The inspectors] didn’t leave us a single document.”

In its official opinion, however, the inspectors documented considerable structural damage, and declared an urgent need for repairs. They cited “fissures”, “flattening in the wall” and “separation of joints” in the staircase – all of which “requires substitution”.

Nevertheless, the residents of the building were never informed, and the necessary repairs were not made.

When the 7.1-magnitude earthquake hit, Rebsamen 241 collapsed. Ana Ramos, one of Acosta Olivares’s neighbours, was trapped inside. Her body was not recovered until nearly two weeks later, on Sunday 1 October.

Many other stories document the same pattern. Across Benito Juárez and Cuauhtémoc, collapsed or damaged buildings had been the subject of citizen complaints.

Many were built after 1985, when another much more powerful earthquake shook Mexico City. After that disaster – when 100,000 buildings were seriously damaged – the city instituted strict new building codes.

The fact that the latest earthquake was roughly a tenth as powerful yet still caused significant destruction has local activists pointing the finger at what they say are shady practices, in which some developers circumvent the regulations and city authorities frequently ignore citizen complaints.

“The whole system is corrupt,” says MacGregor. “And the corruption is deadly. You have a city government that is protecting the developers, not the city.”

The city’s building compliance watchdog told the Guardian it has no authority to crack down on developers. It says it can only pass on information to the relevant municipal agency.

“We warn about risks for the population,” says Francisco Calderón Cordova, communications coordinator at PAOT. “But our recommendations aren’t legally binding, and [other government institutions] don’t always heed our advice.”

In 2016, PAOT investigated all 1,271 citizen complaints of land use and zoning

violations. But PAOT’s role ends once it informs the appropriate agency: most often the Urban Development and Housing Secretariat (Seduvi), but also the Administrative Verification Institute (Invea), the Environmental Secretariat (Sedema) and others.

Although Seduvi does in rare cases punish developers or order repairs, there is no public record of how many of the 1,271 complaints were acted on. Seduvi did not respond to requests for comment.

Mexico City is prone to earthquakes, but the way it has developed since 1985 has made it even more so. Following the disaster, residents abandoned the city centre, as did most investors. The city government responded by introducing incentives for private sector development, and campaigned for infrastructure projects including airports, highways and tunnels.

By 2013, real estate in Mexico City was red hot: between 2000 and 2015 the city’s population grew by just 3%, but the housing stock grew by 20%; in the central areas of Benito Juárez, Cuauhtémoc, Miguel Hidalgo and Venustiano Carranza, it soared by 37%. House prices increased by 7% in 2016 alone.

But the breakneck pace of development eroded its earthquake preparedness. The new buildings often fail to account for the fact that the city was originally built on a lake – and the soft soil can amplify the power of an earthquake.

As developers have tried to capitalise on the housing boom, civil engineers have warned that ever-taller new developments are shifting the soil, drying it out and increasing the earthquake risk. They also say such massive new construction projects can weaken the foundations of neighbouring buildings.

In many cases, developers have been accused of simply flouting the regulations entirely.

At the Nuevo León 238 building in the Hipódromo Condesa neighbourhood, for example, developers added a helicopter landing pad to the roof. When residents complained that the building’s nine stories exceeded the zoning limit and that helipads were not permitted, regulators failed to heed their concern. A spokesperson for the developer, Grupo JV, insisted that zoning requirements had been complied with, and said that a legal ruling permitted the helipad’s construction, even though the company did not have a construction permit from Seduvi. The building partially collapsed in the 19 September earthquake.

One of the key reforms made after 1985 was the creation of a new official to oversee earthquake resilience – the “Director Responsible for Construction” (DRO in its Spanish acronym). Architects or engineers can become licensed as a DRO by taking an exam.

Although meant to increase oversight, cases of crooked DROs abound. From 2012 to 2016, 51 were sanctioned for violations: one DRO was supervising a construction site where seven workers were killed in an accident; others had permitted construction on buildings that exceeded the legal floor limit; yet another supposed DRO was caught using fake credentials.

Nonetheless, in 2016, the office of Mayor Ángel Mancera suspended the legislation that permitted city departments to sanction DROs.

Critics say the move is evidence that the Mancera administration prioritises development over safety. “We have built this city on the whim of the powerful,” says MacGregor.

Newness is no guarantee of a building’s safety.

In Portales, Canada Building Systems opened a “state-of-the-art” tower block at 56 Zapata just this year by with a roof garden and solar panels. On 19 September, a quarter of the building came crashing down. The twisted solar panels now hang off the top of the structure, and an exterior stairwell has crumpled. Two women were killed.

Although the local government of Benito Juárez had given the green light, the DRO who signed off on the project had previously been sanctioned and his licence had expired, according to Mexican media outlets.

In Zacahuitzco, another neighbourhood in Benito Juárez, an apartment building at 90 Bretaña also collapsed. Alitzy Judith Carrillo Quintero, 19, was killed. Afterwards, neighbours said the six-storey apartment block was built on the foundation of a two-storey house without sufficient reinforcement, and that the construction company did not use the proper materials.

In both cases, the Benito Juárez government has said it will prosecute the construction companies. But no explanation has been given for why the Zapata building was approved for occupation in the first place.

The Benito Juárez authorities did not respond to a request for comment.

Several buildings in Cuauhtémoc follow a similar story. In the Tránsito neighbourhood, an 11-storey apartment building at 66 San Antonio Abad suffered major damage. Each of the 55 apartments sold for roughly 1.6m pesos, and the first residents moved in less than a year ago.

Cuauhtémoc delegation chief Ricardo Monreal told the Guardian that the building did not have an occupation permit, and that the delegation will hand over all necessary paperwork to the prosecutor’s office. The building has been cleared for occupation, but many residents are wary of moving back in.Given that so many complaints were ignored before the earthquake, confidence in the safety inspection process is shaken. Four Mexico City residents have set up Salva Tu Casa, an online platform to connect architects and engineers to residents worried about the structural integrity of their homes. Co-founder Alex Rojas says that Salva Tu Casa already has more than 12,000 buildings registered, and called the government’s unresponsiveness frustrating. Seduvi has even referred residents to Salva Tu Casa directly via Twitter. “We built the platform overnight, as a group of volunteers,” Rojas said. “And it seems to have been more effective than the government systems so far.”

“They took away our right to be informed, to understand the risks, and to make our own decisions,” Acosta Olivares said. “Not only did people lose their livelihoods. We also lost a life.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion