Delicate wash cycles should be avoided whenever possible, according to scientists who found they can release hundreds of thousands more plastic microfibres into the environment than standard wash cycles.

Researchers at Newcastle University ran tests with full-scale machines to show that a delicate wash, which uses up to twice as much water as a standard cycle, releases on average 800,000 more microfibres than less water-hungry cycles.

“Our findings were a surprise,” said Prof Grant Burgess, a marine microbiologist who led the research. “You would expect delicate washes to protect clothes and lead to less microfibres being released, but our careful studies showed that in fact it was the opposite.”

“If you wash your clothes on a delicate wash cycle the clothes release far more plastic fibres. These are microplastics, made from polyester. They are not biodegradable and can build up in our environment.”

The finding challenges the assumption that more aggressive washing cycles, which use less water, change direction more frequently and spin at higher speeds, release more fibres into wastewater. Instead, the volume of water used per wash appears to be the most important factor in dislodging fibres from clothing, the study found.

“If the water volume is high, the water will bash the clothes around more than if less water is used,” Burgess said. “The water forces its way through the clothing and plucks fibres of polyester from the textiles.”

The clothing industry produces more than 42m tonnes of synthetic fibres every year. The vast majority, about 80%, are used to make polyester garments. Previous tests have found that washing synthetic items can release between 500,000 and 6m microfibres per wash.

Because many washing machines lack filters that can remove microplastics from their wastewater, the fibres are carried into water treatment plants and can eventually reach the seas. The particles, which come from a variety of sources, are now ubiquitous in the environment, from the deepest marine trench in the Pacific Ocean to the pristine wilderness of Antarctica. Scientists have found the plastics in organisms at every level of the food chain from plankton to marine mammals.

It is unclear what health risk easily ingested microplastics pose to marine life, but researchers fear toxic chemicals in the plastics, and other compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) which stick to them, could be harmful to the animals. The particles may also help spread disease-causing viruses and bacteria.

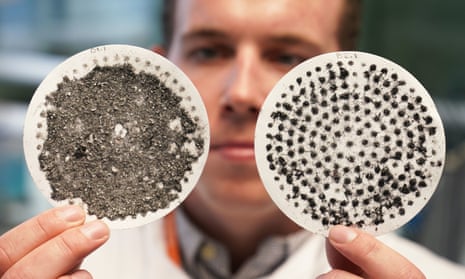

The Newcastle team measured the amount of microfibres released from black polyester T-shirts, first in a series of lab tests that mimicked full-scale washing machines, and then in real washing machines at a Procter & Gamble research centre. The results showed that earlier recommendations to use more water and less aggressive washing cycles may actually be releasing more microfibres into the environment.

Some washing machine manufacturers are introducing microfibre filters, but Mark Kelly, the first author of the study published in Environmental Science and Technology, said avoiding delicate washes and half loads would help to reduce the amounts of microfibres released by washing.

“This research is important as it helps to identify how microfibres are reaching the marine environment,” said Prof Tamara Galloway, an ecotoxicologist at the University of Exeter, who was not involved in the study.

“We have found microplastics in most of the marine animals we study, including turtles, seals and dolphins. Microfibres are the type of microplastics we find most frequently. Whilst we can’t say for sure what the health impacts of ingesting microfibres from textiles might be, minimising exposure has got to be a high priority for protecting the marine environment and the food chain.”