It has started to rain and the angry sky is threatening thunder, but a lone figure is picking his way through the rubble of Dhamar detention centre in Houthi-controlled northern Yemen.

His name is Mustafa al-Adel. Although his brother Ahmed, a guard, died here when the site was recently hit by a ferocious airstrike, he is still employed to watch over the ruins. At night he sleeps in the least damaged building. He doesn’t mind the rain, he says. It has washed away the blood.

“You can see Ahmed’s blue blanket up there,” the 22-year-old said through a mouthful of the stimulant qat, pointing at the second floor of what used to be the guards’ quarters. “There were 200 people here but now it’s just ghosts.”

Adel is one of dozens of people the Guardian met on a rare 6,000km journey through Yemen’s patchwork of Houthi-, government- and separatist-controlled areas, who described how more than four years of war have changed their lives beyond recognition. Suffering is palpable everywhere. But it is in the rebel-held highlands of Yemen’s north that the world’s worst humanitarian crisis has taken root and the spectres of cholera, hunger and Saudi airstrikes loom.

The overnight attack on Dhamar on 1 September was the deadliest so far this year by the Saudi-led coalition of 20 Arab nations fighting to restore the deposed president, Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, according to the Yemen Data Project, a database tracking the war. Even by the standards of a conflict defined by indiscriminate bombing of civilians at markets, weddings and hospitals, the violence was shocking.

At least 100 people died in what eyewitnesses said were seven strikes that pulverised the area. It took five days to remove all the bodies impaled on metalwork ripped from the walls in the blasts.

As a community college campus turned into an informal detention centre, the Dhamar site should have been on the coalition’s no-strike list. It was also an attack that targeted their own: about half of the prisoners were captured Hadi soldiers and half were civilians arrested by the Houthis, said a survivor, Ali Ahmed al-Abasi, 39, from his hospital bed.

Pictures of the burnt and bloody faces of the dead are now on the wall near the entrance for families to come and identify. In some cases there are no faces left: just hands.

“The Red Cross visited us three months ago,” Abasi said. “There is no way the coalition didn’t know we were there.”

The coalition denied it had struck a detention centre, saying it had hit a military site used by the Houthis for restoring drones and missiles.

Strikes such as those on Dhamar that could constitute war crimes hit northern Yemen on an alarmingly regular basis. Saada province, the Houthi heartland on Saudi Arabia’s border, is targeted the most. Barely a street in the town of the same name has been left untouched: the post office, central market and countless civilian homes are gone.

Death comes from above at any time. Over a lunch of chicken, rice and sweet honeyed fatteh, the unmistakable thud of a nearby missile shook the windows of a restaurant. The diners paid no attention to the whine of the Saudi warplane even as it circled back for a second, third and fourth hit.

The scorched earth strategy has not brought Saudi Arabia any closer to winning this war. Its crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, then defence minister, launched Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015 after the Iran-backed Houthis took the capital Sana’a, forcing Hadi to flee to Riyadh.

Quick GuideThe Yemen conflict in numbers

Show

24m people – 80% of Yemen’s population - require some form of humanitarian or protection assistance.

3m people forced to flee their homes.

85,000 - Save the Children estimate that this number of children under the age of 5 may have died through hunger and malnutrition.

1m cases of cholera in 2017, the largest outbreak of the disease in recent history. 2,200 people died during it. A resurgence of the disease saw more than 137,000 suspected cases and almost 300 deaths in the first three months of 2019.

Over 91,600 fatalities since the conflict started in 2015, as measured by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project.

18,292 civilian casualties, including 8,598 killed

4,500 military strikes recorded that directly targeted civilians - outlawed by the Geneva conventions. 67% of the deaths caused in these attacks were by the Saudis and their coalition, with Houthis and their allies responsible for over 16%.

19,990 recorded air raids since the conflict began

£770m - the amount of foreign aid given by Britain in food, medicines and other assistance to civilians over the last half a decade.

£6.2bn - the amount of money Britain has earned in the same period selling arms to the Saudis and their coalition partners.

Zero - despite being 527,970 square kilometres, Yemen has no permanent rivers. Just 2.9% of Yemen’s land is considered to be usable arable land.

However, the Houthis – officially known as Ansar Allah - are an experienced decades-old guerrilla movement. With the help of Tehran, they now possess sophisticated drone technology and can launch cross-border rocket attacks deep into Saudi Arabia, targeting assets such as oilfields, military bases and airports.

Footage of heroic Houthi exploits loops endlessly on the rebel al-Masirah television channel, and Houthi battle songs, known as zawamil, are so catchy even loyalist troops like to play them. The lyrics taunt Prince Mohammed with promises of more Houthi gifts sent over the border.

Some now call Yemen Saudi Arabia’s Vietnam. But the truth is, without a steady supply of weapons, vehicles and technical expertise provided by the UK, US and other western nations, the current stalemate would be even worse for Riyadh.

Yemenis are well aware of where the bombs that fall on their heads originate from. Technical information and serial numbers from missile parts that survive explosions can easily be traced to western arms manufacturers.

At the bomb and mine clearance agency in Sana’a, weapons parts recovered from airstrikes glow hot in the sun. Among them are motor parts from four sensors from cluster bombs – explosives illegal under international law because the submunitions inside released on impact cause indiscriminate harm over a large area. The labels say they were made by the US Goodrich Corporation and manufactured in Wolverhampton, UK.

Goodrich ceased operations in 2012 and it is not known if at the time of manufacture, which could predate the cluster bomb ban, the parts were intended for use in a bomb or later taken into one. Collins Aerospace, formed after Goodrich’s parent company merged its subsidiaries, still operates from the Wolverhampton site.

Aside from waves of airstrikes, life in Sana’a – a city famous for its charming 2,500-year-old architecture, resembling tall gingerbread houses – appears normal on the surface. The Houthis have done a good job of routing al-Qaida from their territory and the streets are cleaner and more orderly than anywhere else in the country.

The relative calm comes at a price: according to Mwatana, one of the only human rights groups still operating, dissenters are routinely imprisoned and tortured, and the Bahá’í religious minority have been persecuted as Israeli spies.

The Saudi blockade of Houthi Yemen’s airspace and land and sea borders keeps the north on a constant knife edge. The Houthi leadership in Sana’a has secured supply lines overland from Oman, diplomatic sources said, meaning they can cling on. But ordinary Yemenis are suffering greatly. The markets in Sana’a are full of produce, but the collapsed economy means food and fuel are now twice as expensive as before the war.

Eighty percent of the population – some 24 million people – are now dependent on aid to survive. Half of that number are on the brink of famine. The UN says by the end of the year the combined death toll from fighting and disease will be 230,000, or 0.8% of the country.

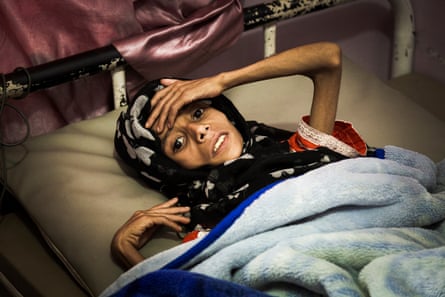

Every hospital in the city is overflowing with malnutrition and cholera patients from families in neighbouring provinces who have scraped together the cash to send loved ones for adequate treatment in the capital.

At al-Sabeen women and children’s hospital, Jamila Mohammed Hamad, 36, says cholera now visits her family every year when the rainy season starts. She lost her three-year-old girl last summer. Now she is back in al-Sabeen’s cholera reception tent, praying her two-year-old niece survives. The little girl, Qasima, was lying on her back gazing blankly at the tent’s ceiling, sweat plastering her curly hair to her forehead.

Men are dying too. Green and flowery posters of those killed fighting and innocents lost to airstrikes cover the walls of homes, businesses, cars and street signs, Hezbollah-style. The pictures of “martyrs” are accompanied by the Houthi sarkha, or scream, which is stencilled in red and green on almost every surface: “God is great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curses on the Jews, Victory to Islam.”

The Houthis began life in the 1990s as a religious protest movement born in opposition to Riyadh’s attempts to spread Wahhabism, the ultraconservative Sunni Islamic doctrine, over the border in Yemen’s Zaydi Shia lands. While at failed peace talks their political agenda appears muddled, they have evolved into a sophisticated military organisation. As the Saudi blockades and air campaign have strangled the life out of entire communities, sympathy for the Houthi cause among many in the north has deepened. Unable to feed their families as work dries up and inflation soars, some men feel they have no choice but to join the movement and draw a fighter’s salary of $100 (£81) a month.

Nowhere is the injustice more keenly felt than in Dahyan, the small village in Saada where a year ago a Saudi airstrike targeted a bus full of little boys on their way to a school trip, killing 44. A piece of the missile seen by the Guardian identified it as a MK-82 bomb. Munitions experts have said it was a laser-guided Paveway, manufactured by the US company Lockheed Martin. Lockheed deferred questions to the Pentagon and US State department. The State Department said it had no comment.

At the site of the attack, 44 small faces now peer down from a banner strung across the street, next to a mural which says: “America kills Yemeni children.”

In the village cemetery, the children’s graves have become something of a pilgrimage site. Twelve-year-old Yusuf al-Amir almost went on the fateful trip: now he visits his friends’ graves most afternoons after school.

Taking his jambiya, a Yemeni ceremonial dagger, from his belt, he cut away a plastic sheet to reveal the twisted skeleton of the bus, which now rests next to the children. A Saudi jet roared overhead as he talked about missing his friends.

In the martyrs’ section of the cemetery, there are two freshly dug graves. The groundskeeper said he was not expecting any green-clad funeral parties today. But he knows more will come.

Quick GuideThe Yemen conflict explained

Show

The roots of the Yemen civil war lie in the Arab spring. In 2011 pro-democracy protesters took to the streets in a bid to force the president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, to end his 33-year rule. He responded with economic concessions but refused to resign.

After protesters died at the hands of the military in the capital Sana’a, there followed an internationally brokered deal to transfer power to the vice-president, Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi.

However, Hadi’s government was considered weak and corrupt, and his attempts at constitutional and budget reforms were rejected by Houthi rebels from the north. They captured the capital, forcing Hadi to flee eventually to Riyadh.

In March 2015 a Saudi-led coalition intervened on behalf of Hadi’s internationally recognised government against the Houthi rebels. The war is widely regarded as having turned a poor country into a humanitarian catastrophe.

Over the years the situation on the ground has become ever-more complex. In September 2019, the Saudi Arabian oil-fields of Abqaiq and Khurais were attacked by air. The Houthis claimed the credit, but Saudi Arabia and the US accused Iran of being behind the attacks. The conflict has been seen as part of the regional power struggle between Sunni-ruled Saudi Arabia and Shia-ruled Iran.

Local militants from al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and from a group affiliated to Islamic State have both used the opportunity to seize territory in Yemen. In August 2019 the Southern Transitional Council, which has up until that point been seen as a UAE-backed ally, attempted to separate itself from Yemen, sparking conflict with the Saudi-led forces. The UAE has now claimed to have withdrawn from the conflict.

Saudi Arabia had expected that its overwhelming air power, backed by the regional coalition and with intelligence and logistical support from the UK, US and France, could defeat the Houthi insurgency in a matter of months. Instead it has triggered the world's worst humanitarian disaster, with 80% of the population - more than 24 million people - requiring assistance or protection and more than 90,000 dead. The charity Save the Children estimated that 85,000 children with severe acute malnutrition might have died between 2015 and 2018.

Medical facilities have been devastated by years of war. The country has had to deal with not just the coronavirus pandemic, but also the largest cholera outbreak ever recorded, with over 2 million cases on record. The UN office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs has warned that more than 16 million people in Yemen would go hungry this year, with already half a million living in famine-like conditions.