For the first time, more women than men are likely to have voted in the Indian elections. That’s more than half a billion women who have had a say on issues that really matter to them. So finally, Indian political parties seem to have woken up to the fact that the female voter matters.

What then, have been her top concerns? According to a recent survey 70% put the safety of women first. Sadly, violence against women is on the rise everywhere in India. Crimes against women are at an unprecedented high while conviction rates are at an all-time low. India has been ranked the world’s most dangerous place for women. While we have traditionally responded to violence in a demure manner, younger, educated Indian women have refused to be stay quiet ever since huge protests erupted across the country following the gang rape of Jyoti Singh in Delhi in 2012.

Safety of girls is another major concern for women. In fact, girls are discriminated against even before they are born, with aborted female foetuses one of the most unacknowledged acts of violence. As a result, there has been a drop in the female sex ratio at birth in 17 out of 21 states.

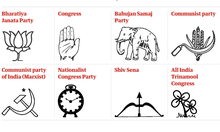

Both the ruling Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) and the Congress party dedicated significantly more space to women in their manifestos than in previous elections. The BJP claimed that its much touted beti bachao beti padhao (“save the girl child, educate the girl child”), and other women-orientated schemes had “gone beyond tokenism” to help achieve gender equality. Yet it was reported that 56% of the money allocated for the BJP’s flagship scheme to educate girls had gone on party publicity. The Congress claimed it has always focused on women’s empowerment as it is the only party to have given the country a female prime minister, Indira Gandhi.

Both parties promised to reserve 33% seats in parliament for women, a pledge made before but never passed by either party when they were in power. In any case, neither party nominated anywhere near 33% women candidates.

So how are women likely to have voted?

Many professional women accused the BJP of paying lip service to gender equality. But others said the BJP had their vote because they see Modi as a strong prime minister who can keep the Pakistanis in their place, and keep Indian borders secure. They dismissed reports of the lynchings of Muslims, murder of journalists and Modi’s silence on attacks against minorities as being grossly exaggerated by the anti-Modi media.

Most rape cases happen in villages, and almost 80% of these rapes are against Dalit women. The National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights, an NGO, says more than 23% of Dalit women report being raped, and many have reported multiple instances of rape.

Meera Velayudhan, a Dalit leader, writer and social activist, had been calling for tactical voting for any party that will defeat the BJP, which she describes as “casteist, anti-Dalit and patriarchical”. “We must vote strategically, for the left in Kerala and the anti-BJP alliances in the other states.”

Most tribal women will have voted for the Congress party because it introduced a minimum guaranteed work scheme for all and provided subsidised rice when it was last in power. Alis Chuwa, a tribal leader, says this “stopped our children from starving”. Chuwa highlighted two major legislations that protected tribals in particular: the 1989 Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled caste (Prevention of Atrocities) Act and the Forest Rights Act . Other tribal women want the banning of alcohol, which they say is ruining their families. Alis says: “Our people brew our own liquor but there are traditional social rules and norms governing its consumption. The BJP has encouraged outside alcohol. And this is not controlled in any way. Our number one priority is having non-traditional alcohol banned.”

Regional parties like the Janata Dal in Bihar and, further south, in Andhra Pradesh, the YSRC, the current opposition party, promised to ban illegal alcohol. Yet, estimates suggest most states earn one-fifth of their revenue from the alcohol industry so it isn’t a popular policy for most parties to adopt.

In Tamil Nadu, the state’s late former leader, chief minister Jayalalithaa, or “mother”, is fondly remembered for delivering a range of schemes for women, including free electrical mixer-grinders. The kitchen gadget took some drudgery out of women’s lives, where arduous hand-grinding with a mortar and pestle to produce the traditional morning idlis and dosas, consumes hours every day. Other gifts ranged from free rice to subsidised food canteens selling hot, cooked meals, to free bicycles for schoolgirls. Pensions for widows and the elderly followed. Kits for newborns were also provided to new mothers in government hospitals. Women in India bemoan the fact that with Jayalalithaa’s death, the women’s welfare schemes have dried up. . This election, women may have switched from Jayalalithaa’s old party, the AIADMK, to the DMK, which promised to reinstate welfare measures for women.

Many Indian women point out the glaring under-representation of women in parliament. Women accounted for 48.53% of the Indian population in the 2011 census but only 12% of members of the last parliament: a meagre 65 out 545, putting India at a woeful 150 out of 193 countries. Notable exceptions to the low turnout of women candidates were the Trinamool Congress of West Bengal, with 41%, and the Biju Janata Dal in Odisha, which fielded 33%.

By and large, poor and minority-ethnic women – Dalits, tribals, Muslims and Christians – were unlikely to vote for the BJP. A viral WhatsApp message has been redoing the rounds. It shows controversial Mahasabha leader Sadhvi Deva Thakur, who makes hate speeches favouring a totally Hindu nation, exhorting India to forcibly sterilise Muslims and Christians.

Educated, liberal women committed to a secular India free of ethnic divisions urged people to vote for anyone but the BJP. I count myself among them. The BJP fought cynically to win women’s hearts and votes. But who knows? India’s electorate has a way of confounding even veteran psephologists.

On Thursday, we will know if women have succeeded in making India a better, safer more hopeful country for themselves and their daughters.