30 years on from the Tiananmen Square massacre, the world is moving backwards

From this distance, the harsh, uncompromising, violent reaction of the Chinese authorities in 1989 was not so much ‘the end of history’ as the beginning of a new normal

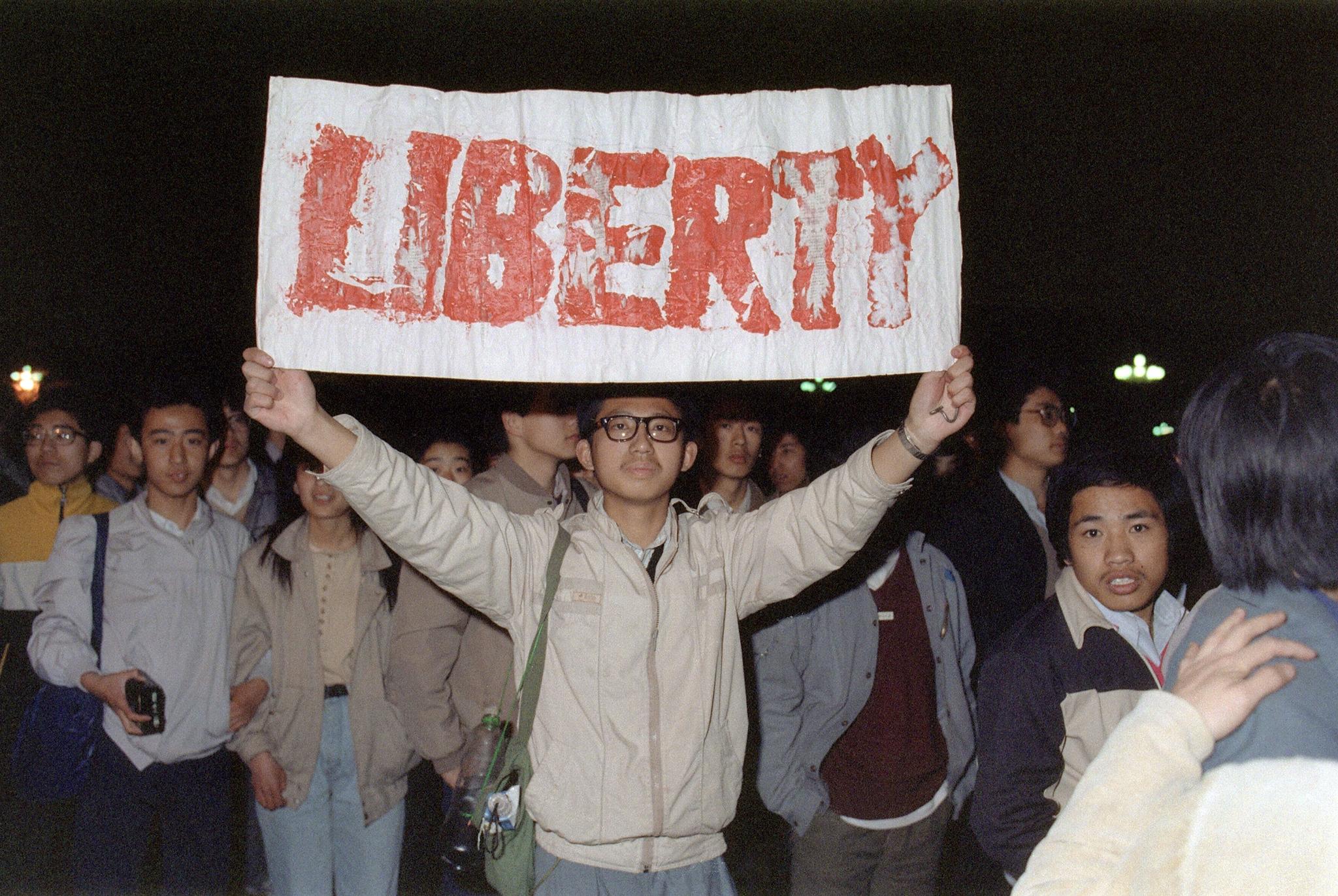

It is now three decades since “tank man” unwittingly created one of the great images of the late 20th century, one that might, for once, be fairly labelled iconic, by standing in protest in Tiananmen Square, carrier bags in hand, ready to die for liberty.

Unlike the 70th anniversary of the foundation of the People’s Republic, and the centenary of the May Fourth Movement, both landmark events in the making of modern China, no one much in that country is commemorating what happened in that brief Beijing spring thirty years ago.

Instead, the government of President Xi prefers to pretend that it simply didn’t happen. Every year the rest of the world bows its collective head in remembrance at the estimated 1,000 who died in confrontations between protestors and soldiers; in China it is studiously ignored by a regime with a firm grip of the political and historic narrative – the great “forgettance”.

Today, as the momentous events of that era are recalled, it is worth mentioning that innocent civilians have, in recent days, been summarily attacked by police and soldiers in places as disparate as Sudan, Venezuela and Pakistan.

Nothing new there perhaps, but yet further reminders of how precious a culture of democracy, free speech and peaceful political change are to any society, and how fragile they can prove.

Tiananmen Square was a moment that seemed to fit with wider trends in the world in 1989. It followed the death of a prominent Chinese reformer, Hu Yaobang. Hu offered the hope to many, particularly students, intellectuals and some in the hierarchy of the Chinese Communist Party that the economic freedoms cautiously and partially launched by Deng Xiaoping a decade earlier would be accompanied by political freedoms hitherto denied the people of China.

The events were looked on first with hope, and then resignation, by the inhabitants of Hong Kong, then in its final few years of British administration. As it turned out, the modest attempts to entrench democracy in the former colony have proved only partly effective at restraining Beijing from curbing dissent.

Today, China has rejoined the world economy, and, on some measures, ranks as the most powerful economic power, eclipsing even the United States. In contrast to the former Soviet Union, where people ran headlong from a communist-planned economy and totalitarian police state to a “wild west” version of capitalism and a crudely functioning democracy, in China the pace of change was more measured, and was not accompanied by the disintegration of the state and economic chaos.

Now China is set upon moving from its past passivity in global affairs towards a more assertive outlook, its Belt and Road Initiative embodying the confluence of geopolitical and global economic power.

Meanwhile, the country’s trade war with the United States is remarkable, by the standards of the past, for two things. First, China is evidently now strong enough – with its trillions of US dollars held in its reserves – to stand up to President Trump; and second, the Chinese are now so integrated with the world economy that the fortunes of the German car industry are intimately linked to Chinese consumer confidence; and the value of the euro goes up and down with the yuan.

Even a decade ago, during the banking meltdown, the Chinese economy was relatively disconnected from that of the west. No longer – and that is a source of strength but also of weakness, as modern recessions can become synchronised and self-reinforcing across continents.

The “end of history”, then, as the triumph of western liberal pluralistic values was so fondly imagined around the time of Tiananmen and the fall of the Berlin Wall, never did quite include the people of the People’s Republic of China.

Indeed, the last 30 years have proved, to the disappointment of democrats and progressives everywhere, that economic freedoms and political freedoms do not necessarily go hand in hand, at least for substantial periods of time.

It may be that, as China become more prosperous, sees its educated middle classes visiting (and studying in) Europe and America, and grows more confident and demanding (having learned western ways), it will change. As it becomes more exposed to the outside world the powerful appeal of democratic freedoms will become attractive to the people and maybe the Communist Party.

Just as the fax machine was an unexpected weapon in the Cold War against Soviet communism, so now could the internet yet prove an unstoppable force in the liberation of China.

On the other hand, from Bolsonaro to Modi, from Duterte to Salvini, and from Trump to Putin, the world seems to be edging towards a new form of semi-democratic, nationalistic, authoritarian rule, different in key respects to the Nazism or fascism of the past, but also carrying some of those same dangerous, not to say evil, characteristics.

From this distance, the harsh, uncompromising, violent reaction of the Chinese authorities in Tiananmen Square 1989 was not so much the end of history as the beginning of a new normal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies