Most people are familiar with the June 1969 rebellion at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village, widely regarded as the opening salvo in America’s LGBTQ rights movement. But years before Stonewall, on the other side of the country, another rebellion is less well remembered.

The Compton’s Cafeteria riot took place in San Francisco in August 1966. Police descended on an all-night diner in the city’s Tenderloin neighborhood, and a group of drag queens and transgender women fought back. And before the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot came Los Angeles’ 1959 Cooper Do-nuts uprising, during which onlookers chucked coffee and garbage at the officers in response to a raid at an LGBTQ-friendly hangout.

These acts of protest have long remained obscure footnotes. Now a new exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California has put them into their proper context.

Queer California: Untold Stories painstakingly assembles photographs, videos and works by contemporary artists to convey 200 years of California’s LGBTQ history. Guest curator Christina Linden credits a gathering of artists and historians more than a year ago for making it all possible.

“We picked sectors of time and populations that are underrepresented in published writing or the archives, and that led me to look as far beyond Stonewall as I could, pushing backwards,” she says.

California has long played an outsized role in the history of the movement. Harry Hay founded the Mattachine Society, an early gay rights organization, in Los Angeles in 1950. In 1961, the San Francisco drag performer Jose Sarria became the first openly LGBTQ person to run for political office, and Harvey Milk won a seat on the city’s board of supervisors in 1977.

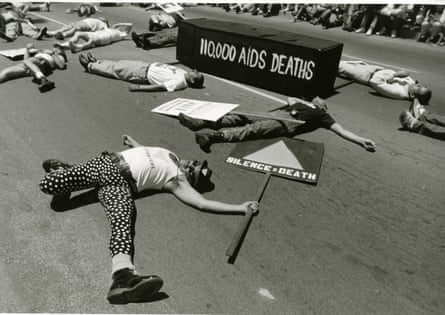

Important though they are, Queer California goes beyond these milestones, displaying a wealth of objects from when queer subcultures flourished away from society’s intolerant eyes. Among the political buttons and the photos of gay motorcycle clubs, some artifacts are simply touching: disco legend Sylvester’s panel from the Aids Memorial Quilt, for instance. The plague years loom large, in images of Act Up’s street protests and “die-ins”, unflinching reminders of when an HIV diagnosis was a death sentence.

Other objects almost defy belief, such as newspaper clippings of an unsuccessful 1970 attempt by a utopian group called Gay Liberation to move to Alpine county, a rural stretch near the Nevada border, in numbers sufficient to take it over. Tribal leaders from the area met with these would-be radicals, cautioning them about repeating a cycle of colonization.

Queer California pays special attention to indigenous people. Through the California Early Population Project’s genealogical records – and inquiries into the archives of several Catholic archdioceses – Linden and her team uncovered journal entries by Spanish missionaries struggling to understand non-binary people.

“It was humbling to be reminded that in fact, these peoples were not extinguished completely, although many, many people were murdered or driven to the point of being re-gendered,” Linden says of her research. “There’s a really vibrant two-spirit population in California who are direct descendants of indigenous tribes who can speak to that history in a direct and personal way.”

Queer California resurrects the stories of those who have been virtually expunged from history. One such figure is Lucy Hicks Anderson, an African American socialite and entrepreneur in Prohibition-era Los Angeles. Later outed as a trans woman, she and her husband were charged with perjury for lying on a marriage license, and convicted after a second trial.

“I have lived, dressed, acted just what I am, a woman,” Anderson said, defiant and decades ahead of her time. At OMCA, she and other trailblazers like her now have their moment of recognition.

Queer California: Untold Stories is on through 11 August at the Oakland Museum of California, 1000 Oak St, Oakland, museumca.org