Timothy, a teenager on the streets of Mombasa, wonders how he will eat. “Rich people can stay home … because they have a store well stocked with food,” he says. “For a survivor on the street your store is your stomach.”

However, says another, if the rumours are true and street children are arrested in the city during the Covid-19 crisis, he’d be happy to go to Shimo women’s prison, because there “you are sure to get free food, shelter and medical services”.

As the pandemic takes hold across the globe, few groups are as vulnerable as the children who rely on the streets for food and shelter, who risk being further stigmatised and criminalised when cities lock down. In Kenya’s second city, a 7pm–5am curfew has been imposed, and fear is mounting.

“We are all really worried,” says Bokey Anchola, country director for Glad’s House, an NGO working with hard to reach young people in Kenya. “Street children are having a rough time during the curfew. Food and water are a real problem as hotels and eating places where they would normally get food have closed down. Movement is restricted.”

The closure of eateries, drop-in centres and feeding services, as well as the limits on movement, are just some aspects of a terrifying scenario for street children during the pandemic, say those working with young people in Kenya and elsewhere.

“Street children are precisely in the space that everyone is supposed to be getting out of,” says Duncan Ross, CEO of UK-based StreetInvest, which has launched an urgent appeal for its partner organisations working with street children and is calling for cities to allow them to lead the response. “The usual response to these children is: ‘how do we get them off the streets’, and Covid-19 has brought this into sharp focus.”

A global total of 100 million street children is often quoted, but the true number is believed to be much higher.

While its partners have not reported police roundups yet, StreetInvest says lockdowns in many cities are still fresh and heavy-handed tactics are likely if the death tolls start rising. Street children are also likely to be caught up in outbreaks in slums, where social distancing and good hygiene are hard to observe.

On Monday plans were announced in Cameroon to clear thousands of homeless children from the streets of Yaoundé, but it was not clear where they would be taken.

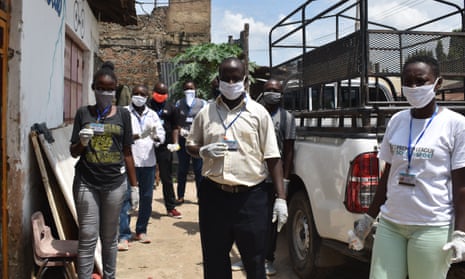

Megan Lees-McCowan, head of Africa programmes at Street Child, said she feared Covid-19 would drive more children to the streets across Africa as schools shut and desperate families looked for alternative incomes. Last week the NGO helped hand out food to children in the Sierra Leone city of Waterloo, near Freetown; some recipients were as young as seven, and had gone for two days without eating.

“For us, there is also the spectre of the past,” said Lees-McCowan, recalling how during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone, some children were abandoned by destitute families, and shunned by communities that suspected they carried the disease.

For Mpendulo Nyembe and his team at uMthombo in Durban, one early casualty of the coronavirus crisis has been trust; until Monday street workers in the South African city had been prevented from doing frontline work while the government took over. Private security firms hired to clear the streets were taking homeless youth to temporary shelters that lack qualified workers to look after them.

“Young people on the streets were asking where we are. They said they were expecting to see our faces. But we couldn’t engage with them. It is not OK that after a week of lockdown I was begging for permission to be with them,” says Nyembe, whose organisation has now received a permit to do outreach work during the crisis.

Before South African president Cyril Ramaphosa announced a three-week lockdown on 27 March, Nyembe and his team were informing homeless youth about Covid-19 symptoms, offering advice and providing food. He is concerned the private security companies have increased fear, citing one encounter between a group of 11 youth and heavily armed guards. “They are terrified. We are terrified. The people dealing with them have no idea who these children are, of their backgrounds.”

Ross says: “The vulnerability of this group will go up [in the crisis], their need for services will go up and isolation won’t protect them. The danger is that many people see them even more as diseased and criminal. Anecdotally, this is already happening.”

A 2016/17 study found there were between 9,000–10,000 street children in Durban, but Nyembe believes the number has since doubled due to the availability of drugs, mainly heroin-based “whoonga”. He warns that the health and lives of children using drugs or alcohol – or who are HIV-positive – are at greater risk if they cannot access the right treatment, or if they have to go through sudden withdrawal.

In Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, many police now understand that for some children the street is home, says Paul Sunder Singh, founder of NGO Karunalaya. But as small businesses have shut up shop in the lockdown, jobs that earned street dwellers a pittance, like carrying goods in markets or selling food to drivers, have vanished. Pavement dwellers are ordered to stay in makeshift structures and can not look for food.

“People’s survival is suddenly in jeopardy. Many families that live on the streets have been there for generations. They have no stocks and could starve,” says Sunder Singh, adding that the government is asking companies and NGOs to donate food.

Another fear is that the virus could drive homeless children back to families where they are at risk of abuse, he says.

There is also a sense that the coronavirus crisis could set back years of progress on childrens’ legal situation, says Siân Wynne, of StreetInvest, pointing out that the UN general comment on street children grants rights to freely assemble in a public space, but that Covid-19 is altering everyone’s rights to occupy such spaces.

Ross says: “If this crisis brings understanding that we need a specific response for street children, that would be a good thing. If it makes other people see these children as we do, as young people with fuller potential who are facing tough challenges, that would also be a good thing.

“We need to deal with the realities of their existence rather than just wish these children away.”

For homeless youth like Alfred, in Mombasa, for now the most pressing reality is the need for food. “The police have told us they don’t want to see us around after 7pm. Are we going to die of hunger instead of coronavirus?”