At 6.30am five-year-old Osman Balama and his mother reach the state hospital of Bobo-Dioulasso, the second-largest city in Burkina Faso. He hasn’t been feeling well for a few days and his mother is worried that he has contracted malaria. The waiting room is already full of mothers and grandmothers with young children on their laps, all with the same tired look as Osman.

“The rainy season has started,” says Sami Palm, head of the clinic. “That means more mosquitos. I’m certain that almost everyone here has malaria.”

Two red lines on the detection strip confirm malaria. “He doesn’t need to stay in the hospital, because he isn’t vomiting and isn’t extremely sick,” Palm says. Osman is sent home with medication – the Burkinese government covers treatments for children aged five and under.

Each year around 400,000 people worldwide die from malaria, half of them in seven countries in Africa, including Burkina Faso. Despite progress in reducing deaths since 2000, cases have been gradually increasing. “We’re having more and more problems with resistance – from the parasite, which knows how to counteract the medicines, and from the mosquitoes, which are getting less sensitive to the insect poisons applied to the mosquito nets,” says Palm. “On top of this, there are many remote areas we can’t reach.”

A radical trial using “gene drive” technology is currently taking place in Burkina Faso, that will see the release of genetically modified mosquitoes in an attempt to wipe out the carriers of the disease.

“We’re developing mosquitoes here that can only have sons. Those sons will also only be able to produce sons, causing the population of females, the only gender that bites, to dwindle until the mosquito is extinct,” says Moussa Namountougou, head of the insect farm of the Institut de Recherche et Sciences de la Santé (IRSS), just a few kilometres from the hospital.

“To do this we have added a bit of genetic information from a slime mould to the mosquito DNA. That extra bit contains the instructions to break down any sperm cells that could produce a daughter mosquito.”

Namountougou and his team have at their disposal a gene drive, which they want to use to stop the genetic instruction diluting as modified mosquitoes mate with those that don’t have the new genetic information. This uses a sort of genetic copier so breed offspring with the new trait – with the intention of wiping out female malaria-carrying mosquitoes. “This way the trait spreads rapidly through the entire population, over just a few years,” says Namountougou. “Such a gene drive has never been released into the wild.”

The village of Bana, near Bobo-Dioulasso, is where GM mosquitoes using this technology will eventually be released. The government gave the go-ahead in June.

Bana is like many others: mud huts around a central square, no sewage system or electricity, the ground strewn with drying shea nuts, whose harvest has just begun.

“We have two major problems here: water pollution and malaria,” says village elder Tchessira Sanou. “I used to go into the forest to gather sticks and leaves from specific trees and shrubs to treat the symptoms. Now we receive mosquito nets from the government and we have medicine, but the disease persists.” Even if no one dies, the disease has a huge impact. “If you or your child get sick, then you can’t work in the fields for several days. That can cost you your entire harvest, leaving you with too little to eat.”

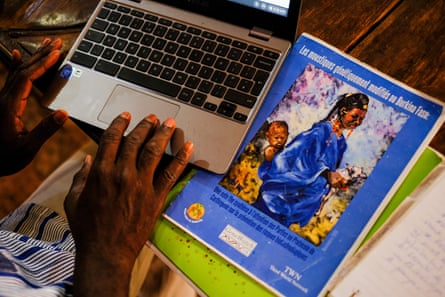

For seven years, Target Malaria, the organisation behind the project – has been sending teams of theatre performers to Bana to explain what scientists are doing in their village.

“It’s very important to us that everyone in the village understands what’s going on here,” says Lea Pare, of Target Malaria.

“Not everyone in the village can read or write, so this helps everyone understand. We need that, or they won’t support the project.”

More than 100 local people have toured the insect farm in Bobo-Dioulasso, where scientists explained mosquitoes’ life cycle, and answered questions.

Genetic modification is controversial, and gene drive technology takes it a step further. Introducing “ordinary” GM produce to agriculture has led to widespread resistance. Several countries have also outlawed the technology.

And there are substantial objections in Burkina Faso. “It makes us puppets of the west,” says Ali Tapsoba, director of Terre à Vie, a community organisation in the capital Ouagadougou. “We believe genetic modification is never a solution. There is always a risk that the mosquitoes will mutate and we will lose track of them. People in our country must learn to live more hygienically, then the malaria mosquito will disappear in a safer way.”

There are doubts too in the academic world. Recently, entomologist Willem Takken from Wagening asked in the Volkskrant newspaper whether another type of mosquito wouldn’t simply take the place of the exterminated insect.

Namantougou already knows the work he’s doing is not nearly enough. “In Burkina Faso there are four mosquitoes that can carry malaria, and we need to tackle each.”

The genetic instruction taken from slime moulds only works in this one type of malaria mosquito, and not in others. “Those will continue to have daughters,” he says.

Bart Knols, mosquito expert at the Radbouduniversiteit in Nijmegen, says bed nets are far more cost effective. “The development of gene-drive mosquitoes is expensive, while a mosquito net costs next to nothing. I think that it’s more effective to invest more money in distributing those.”

Last year, a group of around 160 social and environmental organisations called for a for a moratorium on the experimental use of the gene drive at a UN meeting. It failed by a narrow margin, and many African countries voted against it.

“Opponents of the gene drive should be required to come live here in Burkina Faso for a while and see what malaria brings,” Pare says. “Then they can see for themselves how much we need a solution here.”

As evening falls in Bana, men with mosquito nets arrive and begin swishing them through the air. “These are test mosquitoes, without the gene drive,” says Namountougou. “They have a modification that makes them sterile: no eggs are formed after mating.”

These mosquitoes serve a primarily scientific purpose. “We want to know, for example, how far the mosquitoes travel. We also train people to catch and analyse the mosquitoes.”

One of the catchers shines a flashlight on his net, and at least 10 mosquitoes fly about. The men carefully place their filled nets in a freezer. The following day the mosquitoes will be removed one by one and transported to the lab, where Namountougou will inspect whether they are modified or not. He has great optimism for future possibilities: “The malaria mosquito isn’t the only mosquito causing misery. With a gene drive we can also make dengue, Zika, and chikungunya disappear.”