As they are hauled into Maracaibo’s University hospital, pale, wheezing and panicked, a recurring cry emerges from the mouths of coronavirus patients in this bedraggled Venezuelan metropolis.

“Save me!” they plead as they enter A&E, according to hospital staff too scared to give their names. “Please don’t let me die!”

Many do. Venezuela’s official Covid-19 death toll currently stands at just 329, one of South America’s lowest. By contrast more than 110,000 people have died in neighbouring Brazil and more than 26,000 in Peru, which has a similar-sized population to Venezuela.

But the scenes playing out inside the University hospital – where two of nine floors now host coronavirus patients – suggest the true situation may be far worse.

“The government says everything is under control but that’s not true,” one employee told the Guardian, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of being persecuted by Venezuela’s authoritarian regime. “We have between six and eight deaths a day.”

In one recent three-day period in July, 26 patients reportedly died of Covid-19 there but none was included in the official count.

The investigative website Armando.info claimed the hospital’s doctors had counted 216 patients who died with Covid-19 symptoms – even though the official death toll for Zulia state at that point was just 63.

“We all know what is happening at the University hospital,” one worker said. “But if we speak out they’ll lock us up.”

Coronavirus reached Venezuela later than other countries in the region, perhaps partly because its economic collapse meant there were few flights connecting it to the outside world.

But the pandemic is now shaking South America’s most fragile nation – and even its political elite – with terrifying force.

Several senior figures in Nicolás Maduro’s administration have been struck down in recent weeks including the oil minister, Tareck el Aissami; the communications minister, Jorge Rodríguez; Freddy Bernal, Táchira state “protector”; and Diosdado Cabello, the Socialist party strongman who appears to be recovering after falling seriously ill.

Earlier this month, authorities announced the death of Darío Vivas, the Chavista governor of Caracas and an important Maduro ally.

“He was a man of the people … with an unrelenting desire to live … and this disease caught him off-guard,” Maduro announced in a televised tribute to the 70-year-old.

Outside the capital, the most affected region is Zulia state, of which Maracaibo is the capital, with its Chavista governor, Omar Prieto, also among those infected. Prieto reportedly sought treatment in a private clinic and has recovered.

Most patients are less fortunate and end up in a public health system broken by years of corruption, mismanagement and underinvestment, where the agony of illness is compounded by chronic shortages of medicine, supplies and basic sanitation.

Founded in 1960, Maracaibo’s Hospital Universitario is one of Venezuela’s most important medical centres and its first to perform a kidney transplant, in 1967.

Today, with Venezuela and its health service in ruins, the hospital has no functioning toilets and often lacks water to bathe or clean. Patients have reportedly been forced to defecate on lunch trays and throw their waste from the window. To reach dialysis, patients with kidney disease must trek through the floors housing Covid-19 sufferers because the lift is broken.

One health worker said the situation was so dire many Covid-19 patients preferred to suffer at home. “They don’t want to come in because they think they’ll be left to die.”

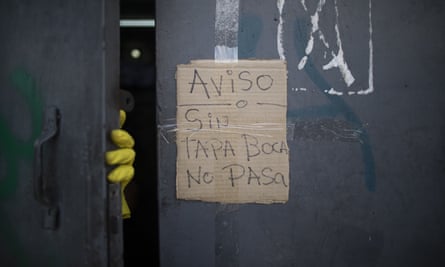

Medical staff meanwhile lack face masks and gloves and cleaners are without mops and disinfectants.

Julio Castro, an infectious diseases specialist from the Central University in Caracas, said doctors across Venezuela were facing similar shortages, with 40% of hospitals unable to furnish staff with sufficient personal protective gear (PPE).

That has proved disastrous for frontline health workers. Twenty-three doctors have so far died in Zulia alone, including Luis Felipe Salazar, the director of Maracaibo Central hospital. Nationwide at least 71 health workers are reported to have lost their lives.

“Doctors and nurses cannot continue being the first victims – the tragedy will be infinite,” said Daniela Parra, the president of Zulia state’s medical association.

Maduro painted a conflicting picture in a recent propaganda broadcast, presenting a series of films in which recovered Covid-19 patients praised the treatment they received at Maracaibo’s University hospital.

“The governor, Omar Prieto, and the president, Nicolás Maduro, are doing everything they can to ensure every Venezuelan gets the care they need,” one recovered patient, identified as Leonardo Rodríguez, claimed in one film.

“I recommend you go to University of Maracaibo … I went in thinking I wouldn’t make it out alive and I came out reinvigorated, healthy and happy,” Rodríguez added.

Last week, Prieto said the hospital was treating 172 patients, eight of them in intensive care. On Thursday one doctor said the number of patients and deaths finally appeared to be falling. “Glory to God,” Freddy Pachano tweeted.

The true scale of Venezuela’s Covid-19 crisis is impossible to gauge but Castro said he feared it was in the early stages of an “exponential rise” in infections that could prove devastating for a country already on its knees.

“There’s no reason to believe the situation will be any different” from Brazil, Peru, Mexico and Colombia where the combined death toll is more than 200,000. “It’s the same virus and these are similar places.”

“We are probably about one month behind Colombia and one and a half or two months behind Brazil,” warned Castro, who advises Venezuela’s political opposition.

Maracaibo’s first Covid-19 case – a 56-year-old man who had returned from Spain – was detected at the University hospital on 19 March, nearly a month after the first cases were recorded in neighbouring Brazil.

But it was when the virus found its way into the city’s enormous open-air market – Las Pulgas – that the calamity began to accelerate. The majority of Zulia’s 4,898 cases are clustered around the sprawling flea market, which is visited by as many 30,000 people each day. Few wash their hands, let alone use hand sanitizer or masks.

On 24 May the state governor ordered the market shut after confirming “a serious outbreak” – but the damage had been done.

Despite the apparently worsening situation, Maduro recently announced a partial reopening in seven regions, including Zulia, followed by a seven-day period of “radical quarantine”.

“We are fighting an extremely tough battle to stop this growing, to prevent more deaths,” Maduro said in a recent televised broadcast.

“My responsibility as president is to care for you, to save you, to break the chains of transmission – but I can’t do it on my own, I’m asking for your help, fellow countryman.”

Castro said he was perplexed by Maduro’s decision to partially relax containment measures “in a country where the number of cases is growing by an average of 130% each week”. “The epidemic is advancing,” he warned. “The situation is really worrying.”

Such is the number of cases in Zulia, where the government says 40 hospitals now receive Covid-19 patients, that authorities have commandeered more than 20 motels and hotels to house quarantined patients.

One intern said they had been stuck there for nearly three months after testing positive on a rapid coronavirus test.

“We’re being held prisoner here – there are no doctors to examine us and nobody tells us what is going to happen,” they said, also speaking on the condition of anonymity.

“Nobody knows what is going to happen. Nobody knows who’s been infected and who hasn’t,” the intern said. “Nobody knows when we’ll get out of here.”

Sheyla Urdaneta contributed reporting from Maracaibo, Venezuela