Covid-19 is a never-ending lesson in the history, legacy and reality of structural racism in America. We see it everywhere the pandemic forces us to look: in infection rates, unemployment, housing insecurity and the loss of life. It’s also glaring in an area that has not gotten enough attention: lack of access to safe, affordable water.

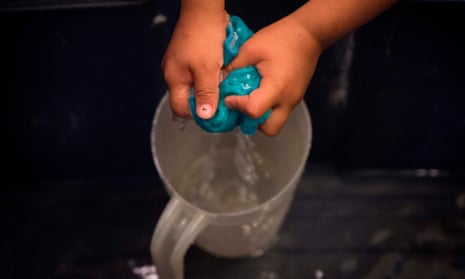

It is no coincidence that many of the current Covid-19 “hotspots” have been in cities and communities with majority-black or Indigenous populations – places where residents have been fighting for years for reliable, affordable access to safe water. As medical experts continue to strongly urge the public to wash our hands and sanitize our surroundings, the advice is hollow in communities plagued by tainted water, crumbling sanitation systems or none at all, or unaffordable water bills and service shutoffs. Covid-19 exposes the dangers and immorality of decades of underinvestment, unjust policies at all levels of government, and society’s disregard for the wellbeing of millions of low-income people and people of color. In essence, the policies that deprive people of color of access to drinking water are no different than any other acts of unjustified violence such as police brutality, militarized streets and electoral injustice. We are bearing witness to the interconnected nature of it all as people are taking to the streets demanding change. Flint still does not have water.

Nearly a quarter of the US population, 77 million people, are served by drinking water systems with known Safe Drinking Water Act violations. As local and state governments increasingly shoulder the expense of maintaining and repairing old, fraying systems, the costs are passed down to consumers, though they are not responsible for the problems and in many cases they cannot afford higher rates. Before the pandemic, an estimated 15 million people, mostly people of color struggling with poverty and unemployment, experienced water shutoffs when they couldn’t pay their bills.

When Covid-19 struck Detroit, for example, an estimated 2,800 homes were experiencing water shutoffs. More than 100,000 Detroit homes have had their water turned off at some point since 2014. We the People of Detroit co-founder Monica Lewis-Patrick has worked tirelessly to put bottled water into the hands of residents. In the face of the pandemic, they had to choose between hydration and hand washing. African Americans make up close to 14% of the population in Michigan, but about 40% of the state’s 1,076 coronavirus deaths as of 9 April. Water is by no means the only factor behind these devastating statistics, but access to clean water is the most fundamental element of infection control, and it’s critical to good health.

In the Navajo Nation, an estimated 30% of people do not have running water and must haul barrels to meet their needs, according to the 2019 report Closing the Water Access Gap in the United States. Many also lack access to wastewater systems, and some households rely on unregulated wells, springs or livestock troughs for water, which can be unsafe because groundwater is contaminated by abandoned uranium mines. These conditions are rooted in a history of US government violations of tribal water rights. The well-documented health impacts of poor water access in the Navajo Nation include higher rates of diabetes and other conditions that make people especially vulnerable to Covid-19. As of 25 May, the Navajo Nation had 4,794 confirmed Covid-19 cases, the highest infection rate in the United States.

In this public health crisis, some government leaders are taking action. The Michigan governor, Gretchen Whitmer, issued a statewide Covid-19 moratorium on water shutoffs in homes with unpaid bills and ordered service restored to homes that had been disconnected from water supplies. The Michigan representatives Rashida Tlaib and Debbie Dingell have introduced the Emergency Water is a Human Rights Act, which would prohibit water shutoffs and require reconnections nationally during the Covid-19 crisis.

The Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act (Heroes Act), a $3tn Covid-19 relief bill put forward by the House of Representatives, has two key provisions that would advance water equity and other environmental justice issues: (1) $50m in grants to investigate or address the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic in environmental justice communities; and (2) $1.5bn in grants to states and tribes to subsidize water costs for households at or below 150% of the federal poverty level, and to keep or restore water access.

If Congress takes full advantage of this current crisis, it will not only rectify a profound injustice by helping to speed the flow of safe and affordable water to millions, it will be making a down payment on the long-term investments needed to build the next generation of sustainable, green and publicly owned water infrastructure.

Indigenous communities rightly refer to water as a relative, reminding us that we are deeply connected to water and should treat it with respect, care and humility. Water is life-giving, life-sustaining, and lifesaving. Covid-19 should spur the nation to rethink policies and practices that treat water as a commodity – an increasingly unaffordable one – and reimagine it as an essential resource that must be available to all.

Ronda Lee Chapman is a senior associate at PolicyLink