The last words Evelyn Namulondo said to her elder sister, Jennifer, were: “It’s over, I am going to die.” It was 15 May and the 30-year-old was in a hospital bed in Jinja, Uganda, two days after being shot by unidentified men apparently trying to enforce Uganda’s 7pm to 6am coronavirus curfew.

Namulondo was on a motorcycle taxi at 5am, heading to the restaurant she co-founded, when men she thought were police officers asked the driver to stop. When the taxi sped off instead, they fired, hitting Namulondo.

“I told her, ‘Just pray to God to heal you.’ But she said she was in too much pain,” Jennifer says between sobs. “Evelyn cried, ‘I don’t think I will survive, I don’t think I will ever walk again.’”

Namulondo is one of at least 12 people reported to have died at the hands of security personnel enforcing Uganda’s lockdown, with several others badly injured. There were dusk-to-dawn curfews and a ban on motorcycle taxis carrying passengers.

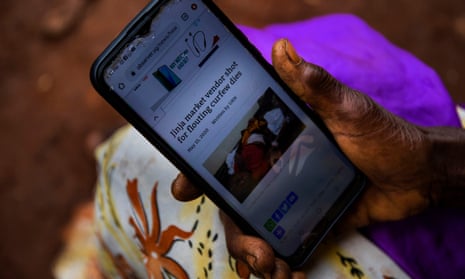

Hours after Namulondo was shot and about 35 miles (60km) from where the incident took place, Eric Mutasiga, a 30-year-old primary school headteacher in Mukono, who co-owned a grocery kiosk with his wife, was shot in the leg by police officers in front of the stall. The incident happened as he pleaded with the officers not to arrest a chapati seller on the street outside, who was still serving three minutes past the 7pm curfew, his family say.

“He came out of the kiosk to plead for the boy. He was asking the policemen, ‘Please don’t take him’,” Mutasiga’s mother, Joyce Namugalu, says. “The policemen refused, then he left and started walking back to the kiosk. On his way back to the kiosk, he was shot in the leg from behind.”

Mutasiga was taken to hospital and died during surgery at the beginning of June.

The Ugandan police told local news outlets that the two officers involved had been arrested and that the force was considering murder charges against them.

Shortly after the incident a Kampala police spokesperson was reported to have told journalists that Mutasiga fought with the officers. However, Mutasiga’s wife, Viola Nabatanzi, who saw the incident, denies there was a scuffle.

“People started gathering and my husband just peacefully walked away from the police when they refused to listen to him, which is when he was shot,” she says.

Mutasiga’s mother says she has not heard from the police. “I do want justice,” she says. “At least they should compensate for his life, he was still a very young man.”

Mutasiga’s wife says the family have run out of money and cannot afford to keep up the fight. “My husband is already dead, he is gone, even if I fight tooth and nail, he will not come back,” she says.

Namulondo’s family say they were told that the men who shot her were rebels and not police officers. They, too, want justice, but their quest for answers has been hampered by Covid-19 movement restrictions.

Namulondo’s mother, Grace Nake, says the family need help with bills. “As much as I want justice for my daughter, all I want is assistance. If they are to imprison the people who did this to her, what is our benefit in that?”

Eron Kiiza, a human rights lawyer in Kampala, points out that poor people cannot afford legal action to seek damages. “Justice doesn’t move towards the people, they have to go to it,” he says. “Even access to justice calls for some modicum of resources, which some people do not have.”

With four children aged between two and eight to feed, Namulondo’s family remember her as a hard worker. She left the village for the town, despite several hurdles, to support her family.

“My daughter was my sustainer, she was always there for me in everything. I was so attached to her, she was my life,” 67-year-old Nake says, wiping her eyes.

The last time Nake saw her daughter was several months ago when Namulondo had been bitten by a dog. She had taken her some medicine. “I told her, I don’t like you staying in [Jinja], I want you to come back to Bukagbo [the village where she was born] and stay here with us.”

Nake says that Namulondo told her that she couldn’t leave because she had debts to pay and that she would return home as soon as she cleared them. She never did.

Jennifer says she will never forget her sister’s love for others, which stayed with her until her final moments.

“All she cried about was the sorry state of her children, that she was scared of leaving, and her ageing mother who she knew wasn’t doing very well,” she says. “Evelyn cried, ‘I am dying but my children … my children’.”