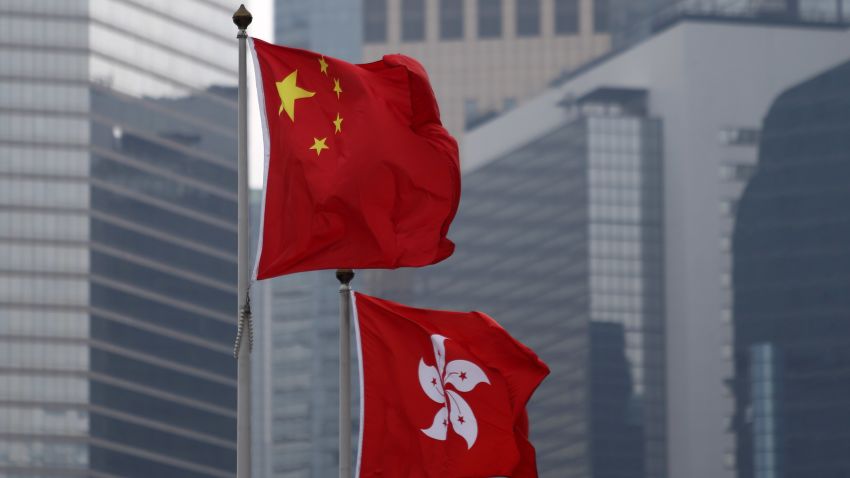

A year ago, Hong Kong was in the throes of political crisis, with riot police and anti-government protesters facing off in the streets amid calls for greater democracy.

These days, the streets are mostly clear; protest art and slogans have been scrubbed off walls; politically sensitive books have been removed from library shelves; and now, the city is about to lose almost all of its opposition in government.

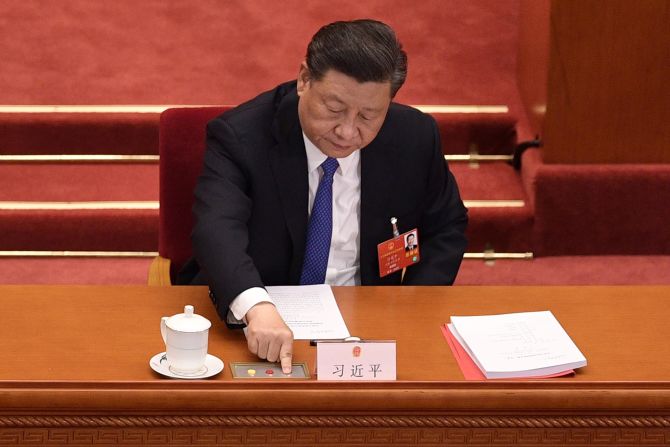

On Wednesday, the Beijing government passed a resolution allowing Hong Kong authorities to expel locally elected lawmakers, without having to go through the courts.

Immediately afterwards, four elected pro-democracy lawmakers were ousted from the city’s legislature – prompting the entire pan-democrat opposition bloc to announce their intention to resign in protest.

The development marks the latest, perhaps fatal, blow to Hong Kong’s embattled pro-democracy movement in a year that has seen authorities crack down on political dissent, arresting campaigners, activists and politicians.

Here’s what you need to know about the legislature turmoil, and how we arrived at this point.

What is the resolution?

The National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp parliament, ruled on Wednesday that the Hong Kong government had the power to unseat local elected lawmakers if they “fail to uphold the Basic Law of the Hong Kong SAR of People’s Republic of China.”

Under the resolution, elected members of the city legislature can be expelled if they “promote or support” Hong Kong independence, endanger national security, seek foreign interference in local affairs, or “refuse to acknowledge China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong.”

Let’s break down some of these terms:

- The Basic Law is Hong Kong’s mini-constitution. It was adopted in 1997, when the former British colony was handed back to mainland China. Under the terms of the handover agreement, Hong Kong was supposed to maintain a high degree of autonomy from China in everything apart from defense and foreign affairs.

- The handover agreement included clauses protecting freedoms of speech, press, and assembly, for 50 years – which are written into the Basic Law.

- Hong Kong independence refers to the idea that Hong Kong – which is a semi-autonomous Chinese territory – should be politically separate from the mainland.

What happened after the resolution?

Immediately after the resolution passed, the Hong Kong government disqualified four elected pro-democracy lawmakers: Alvin Yeung, Dennis Kwok, Kwok Ka-Ki and Kenneth Leung.

Later that evening, Hong Kong’s leader, Chief Executive Carrie Lam, said in a news conference that lawmakers who do not respect China’s sovereignty “cannot genuinely enact the Basic Law so they cannot genuinely perform their duties as legislators.”

“I welcome diverse opinion in the legislative council and respect the checks and balances,” Lam said, adding that “all of those responsibilities must be exercised responsibly.”

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs also defended the resolution, saying it was “reasonable, constitutional, and legal.”

Shortly afterward, the 15 remaining pro-democracy lawmakers announced they would also step down en masse in protest and solidarity. They are expected to hand in their letters of resignation individually throughout Thursday.

Countries including Australia, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom have voiced their opposition to the resolution and the lawmakers’ disqualification.

What’s the National Security Law?

Underpinning all this is the sweeping National Security Law, which criminalized secession, subversion against the central Chinese government, terrorist activities, and collusion with foreign forces to endanger national security.

Beijing promulgated the law in June, completely bypassing Hong Kong’s legislature. The contents of the law weren’t even revealed to the public until after it was passed.

The law allows mainland Chinese security agents to operate in Hong Kong for the first time, gives Beijing the power to override local laws and impacts broad swathes of Hong Kong society – as well as foreign nationals overseas.

The crimes are vaguely defined and wide-ranging; for instance, it’s now a crime to work with a foreign government or organization to incite “hatred” toward the central Chinese government. Calling for Hong Kong independence counts as a crime under “secession,” and vandalizing public property or government premises – as protesters did for months last year – are acts now deemed to be terrorist activities.

People face a maximum penalty of life imprisonment for all four crimes.

Some context: While Hong Kong has an independent legal system, a back door in the Basic Law has long allowed Beijing to make law in the city. There wasn’t much the Hong Kong public or leadership could do when Beijing used this to pass the national security law.

The law was met with criticism and concern from the international community; in August, the United States sanctioned Lam and other Hong Kong officials, with Secretary of State Pompeo stating that their actions were “unacceptable.” On November 10, the US sanctioned four more individuals for their involvement with the law, including officials in mainland China.

So what does this mean?

Under the national security law, political protest is outlawed and residents can’t voice any meaningful opposition to the government without risk of imprisonment.

The city’s legislative council was one of the last avenues for residents to voice dissent – but this, too, was effectively closed off by Wednesday’s ruling. If the remaining pan-democrat lawmakers resign, as expected, the city’s opposition could be left without any political representation.

Many residents and politicians decried the ruling as a sign that the “One Country, Two Systems” framework, designed to give Hong Kong greater autonomy from the mainland, is now officially dead.

Under this model of governance, which was set up during the 1997 handover, the city is part of China – but it has civil freedoms, as well as its own currency, legal system, immigration and customs, and international trade agreements.

For many Hong Kongers, the resolution represents China’s growing control over the city, and over institutions that were supposed to remain independent under that framework.

Protests were raging a year ago. What happened?

The pro-democracy, anti-government protests started last June as peaceful mass marches in opposition to a bill that would have allowed extradition of fugitives to mainland China. At their peak, the demonstrations attracted crowds of more than two million people, according to organizer estimates.

With the government refusing to back down, however, the marches descended into clashes with police – and the movement quickly grew to include five major demands, including universal suffrage and an inquiry into alleged police brutality.

Lam withdrew the extradition bill in September, but it was too late to quell the protests, which continued through the year.

New security law sparks protests in Hong Kong

The arrival of Covid-19 led to a pause, as millions of residents stayed home and avoided crowds. Beijing took advantage of the lull to take action, fast-tracking the national security law.

Since then, police have raided the headquarters of pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily and arrested its founder. A number of civilians, protest leaders and pro-democracy lawmakers have been arrested. Activists and former protesters are fleeing and seeking asylum in other places.

The protest movement has now been pushed underground – but on Wednesday, some of the disqualified lawmakers tried to project a message of hope.

“I have faith the talented & courageous youth will help build our city for better,” expelled lawmaker Alvin Yeung wrote on Twitter. “I love HK, this is a firm conviction that I will not yield to any new challenges now and ahead.”

Long death of democracy in Hong Kong

The fight for democracy in Hong Kong, and the slow strangulation of opposition, began long before the national security law.

Though discontent had been simmering for years, it erupted in 2014 when protesters occupied the city’s financial district for 79 days. The protests, dubbed the Umbrella Movement, failed to achieve any concrete change – but garnered international attention and awoke a generation of activists and politicians.

People took to the streets again in 2016, after the government disqualified several pro-democracy lawmakers who had been elected to the Legislative Council. The ruling came after Beijing made a dramatic intervention, employing a rarely-used power to reinterpret the Basic Law.

The string of expulsions continued in 2017, with more pro-democracy lawmakers disqualified from their posts for failing to take their oaths properly. In 2018, the government banned a pro-independence party, making it illegal to be a member or to act on its behalf.

A number of other incidents sparked controversy leading up to last year’s protests, such as the jailing of several protest leaders from the Umbrella Movement, and ominous warnings from Chinese President Xi Jinping.

CNN’s James Griffiths contributed to this report.