Tens of thousands of Cambodians are going hungry under the country’s strict lockdown as Covid cases continue to rise amid criticism from human rights groups that the government and the UN are being too slow to act.

The south-east Asian country had recorded one of the world’s smallest coronavirus caseloads, but infections have climbed from about 500 in late February to 20,695 this week, with 136 deaths.

A three-week blanket lockdown in the capital, Phnom Penh, was lifted last week but more than 150,000 people are still living in designated red zones in cities across Cambodia, forbidden from leaving their homes other than for specific medical reasons. Many have been living under the country’s most restrictive lockdown measures since mid-April and have not been able to work or get food, medicine and other necessities for weeks.

“This is a humanitarian crisis for the people involved,” said Brad Adams, Asia director of Human Rights Watch. “For those stuck at home without enough food or medical support, this is a government-created crisis. There’s a way to deal with public health concerns that does not require people to go hungry.”

Bopha Moung (not his real name), 65, is trapped in his 25 sq metre home, made from corrugated iron, in a red zone in Phnom Penh with his wife, four children and two grandchildren. The last time he ventured out was on 12 April to get food.

“We are really scared and worried about not having food,” said Moung. “We have lived with the assistance of our neighbours who gave us 5kg of rice. We can’t come out of the house because the zone is blocked off by a barricade.”

On 5 May, a loudspeaker announcement said a couple of cases of Covid had been detected in the area and that everyone should stay at home until further notice. Moung and his children have not worked since lockdown was imposed and what little savings he had are fast running out.

He has to make monthly repayments of $150 (£106) for a loan he took to pay for his tuk-tuk, but he has no income. He said many in his area are in the same predicament. He has received no help from the government or any organisations. “We are living in misery, we don’t eat enough, we skip meals.”

On 18 April, a group was established on the Telegram messaging service by the Phnom Penh authorities to coordinate emergency food requests. Ten days later, the group had more than 50,000 members and contained thousands of messages pleading for food and support. By 23 April, members were asking why they had received no response to their calls for support. The group was suspended on 6 May, according to the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defence of Human Rights (Licadho).

Touch Channet, a 33-year-old garment worker, is in forced quarantine after she travelled from a red zone in Phnom Penh to make a religious offering for her husband, Chi Chii. He killed himself on 23 April while she was in the next room. She was not able to attend his cremation and has not picked up his ashes.

Chi Chii worked in construction and the couple rented a room with their five-year-old daughter. When lockdown was imposed in mid-April, their food supplies of eggs, tinned fish and noodles lasted for a week. Channet’s mother borrowed money to help them out.

Now Channet is $1,500 in debt with no income and no job. “I am really, really worried about not having a job, and having to pay back the loans with interest,” she said. “I’m very sad and worried about my husband’s death. It hasn’t sunk in yet. I don’t know how I’m going to bring up my child. All kinds of things make my heart really sad.”

The Cambodian government has denied local and international groups access to provide assistance to those most affected by the crisis. Phay Siphan, a government spokesperson, said people claiming they had no access to food were “liars”. The commerce ministry has set up an online food store for red-zone residents, selling a limited range of items. Several of these are supplied by companies closely linked to senior officials in the ruling Cambodian People’s party, leading to claims of profiteering and cronyism.

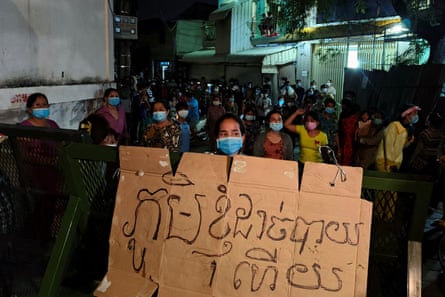

Those who have spoken out have faced violence from police, who have posted videos of beatings on social media, according to human rights groups. Others have been arrested.

Naly Pilorge, director of Licadho, said: “This pandemic has been mismanaged by the Cambodian government. It has shown the problems festering in Cambodian society, including corruption, poor governance, debt and the vulnerability of women, children and people with disabilities.”

She asked why UN agencies with “big budgets” had not taken action earlier to prevent Cambodians suffering.

Adams, at Human Rights Watch, said he also thought the UN deserved criticism. “The primary villain here is the government but the UN still has to do its job,” he said.

“I want the UN to publicly demand access on an emergency basis to allow it and NGOs to provide food and other necessities to people in lockdown areas,” he said. “They should be insisting they be allowed to do this as part of their mandate and to make sure the government’s legally binding human rights obligations to ensure everybody has access to food and healthcare and other necessities are upheld.”

Pauline Tamesis, UN resident coordinator in Cambodia, said: “The UN’s priorities are, and continue to be, in saving lives and stopping the transmission of the virus; mitigating the socio-economic impact on the most vulnerable Cambodians and recovering better from the pandemic.”

She said UN agencies had spent more than $100m in the country since 2020 and that it was calling for access to the red zones to provide emergency food assistance and other basic amenities to those in need.