The Covid-19 crisis has claimed over 450,000 lives in Brazil, and wrecked the livelihoods of so many more. Brazilians are facing one of the worst economic recessions in the country’s history. Millions remain unemployed, inflation is climbing, countless businesses are going under, and people are going hungry.

“It is the new lost decade, worse than what we had in the 1980s,” says Claudio Considera, economist and coordinator of the National Accounts Center at Getulio Vargas Foundation.

After several decades of economic prosperity, the oil glut of the 1980s slapped Brazil with soaring foreign debt, a drastically devalued currency and hyperinflation to the tune of over 200%. For the next decade, Brazilians suffered through wage freezes, skyrocketing food prices and empty market shelves.

After a period of recovery thanks to economic reforms and a more stable, democratic government, Brazil dove back into its longest and deepest recession from 2014 to 2016 under former President Dilma Rousseff’s administration, who was impeached after botched public spending sank the economy and stoked inflation.

“From then we weren’t able to recover growth, and then the pandemic came in 2020 and threw Brazil into an even worse scenario,” adds Considera.

The election of Jair Bolsonaro in 2019 did little to right Brazil’s path toward economic growth. Economic reforms including privatizing state-run industries, labor and pension reforms failed to remedy rampant unemployment and inflation.

Then the pandemic struck.

Avoiding restrictions ‘at all costs’

Since the arrival of Covid-19 in Brazil, the federal government has followed a policy of staunchly avoiding restrictions “at all costs,” hoping to ride out the contagion of Covid-19 without drastic effects on economic activity.

On May 15, 2020, President Bolsonaro gave a press conference declaring that lockdown measures would be “a pathway to [economic] failure.”

Nearly a year later, on February 23, he emphasized, “This lockdown story, the ‘we are going to close everything’, is not the way. This is the path to failure. It will break Brazil.”

In March, Bolsonaro even asked Brazil´s state prosecutor to file a request to the country’s Supreme Court to prevent governors and local officials from imposing lockdowns. When the court dismissed the case, Bolsonaro told supporters that “chaos is coming. Hunger will push people out of their houses, we will have problems that we never expected to have, very serious social problems.”

Indeed, many Brazilians have faced grave economic consequences due to the pandemic. Nilza Maria da Silva was one of them. Living in the favela Paraisopolis in the south of Sao Paulo, the 45-year-old lost her cleaning job as soon as the pandemic started.

“My bosses were afraid of Covid-19, nobody wanted me inside their houses and I was left with nothing,” said da Silva, a mother of four.

More than 8.1 million people in Brazil lost their jobs between January 2020 and January 2021. The unemployment rate in Brazil reached a record of 14.7% of its working age population, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). It is the highest unemployment rate since IBGE began keeping track in 2012.

But many experts say the fact that the economy was actually harmed by the fact that the coronavirus was allowed to spread uncontrolled – and believe that the Bolsonaro government could have staved off some economic pain by making a greater effort to stop the virus.

Thomas Conti, an economist at Insper Institute and science communicator at the InfoCovid group which works on the publishing of scientific information, says government denialism, refusal to adopt lockdown measures and failure to obtain early stores of vaccines created a dangerous sense of uncertainty in the economy.

“When a pandemic of this scale occurs, the economy will suffer a blow even if nothing closes. People are affected by risk. When people understand they are at risk, that they can lose their lives or the lives of close ones, they change habits, they avoid exposing themselves, regardless of measures,” said Conti.

“The role of a government in such a situation is to try to control or mitigate the risks, but they decide to do nothing to combat the pandemic as if it would magically disappear. That created a sense of uncertainty, insecurity and unpredictability. This poses a great risk for entrepreneurs, it makes companies fire staff, it makes people spend less to save, it pauses investments,” he added.

Help, but not enough

In reaction to the crisis in the labor market during the pandemic, the main public policy adopted by the Brazilian government was emergency aid.

The federal government offered a line of credit to pandemic-affected small businesses, though the aid only reached a small portion of Brazilian businesses and the offer of loans rather than handouts proved risky for many business owners. As a result, tens of thousands of retail shops closed in 2020.

Congress also passed emergency aid requiring government support for those individuals hardest hit by the pandemic, with a program that paid five monthly installments equivalent to USD 110 per qualifying recipient between April and August 2020, and four installments of USD 50 between September and December.

Nearly 70 million Brazilians benefitted from the program, according to the Economy Ministry.

Da Silva says the government aid was just enough for her family to get by in 2020. However, government assistance has decreased since 2021, and she has had rely on neighbors and local associations for sustenance.

“I didn’t go hungry because the Paraisopolis community is very organized and helped me with food, because it is all very expensive now. But there were times I had no money to buy cooking gas and had to use firewood to cook,” she said.

And not every community in Brazil is as helpful as Paraisopolis. Research led by the Brazilian Network for Research in Sovereignty and Food and Nutrition Security found that more than half of Brazil’s population -—116 million people — did not have full and permanent access to food last year.

Business shuns Bolsonaro’s approach

Today, even the financial sector, which has supported Bolsonaro since the beginning of his government, has grown weary of his approach. In a letter signed by over 1,500 economists, bankers, businessmen and former ministers criticized the government’s pandemic response and stressed the need to rein in the virus to save Brazil’s economy.

“This recession, as well as its harmful social consequences, will not be overcome until the pandemic is controlled by a competent federal government action. This government underutilized or misused the resources at its disposal, including by ignoring or neglecting scientific evidence in designing the actions to deal with the pandemic,” says the letter, which calls for faster vaccinations, more mask use, economic aid, and a national lockdown if necessary.

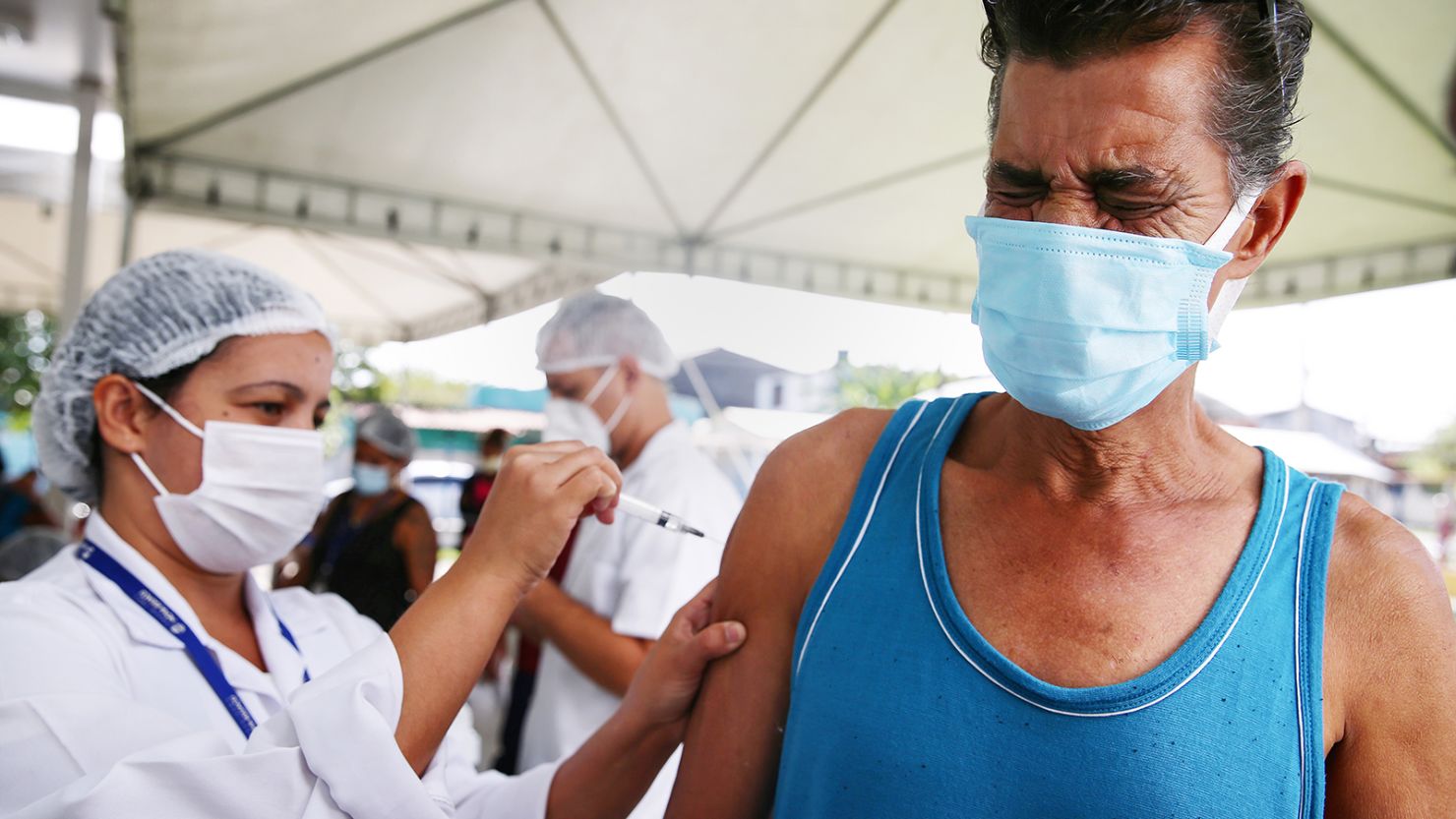

Brazil continues to rank second for Covid-19 deaths among countries globally. While the daily death rate has come down from its peak of 4,000 average daily deaths to roughly 2,00, cases and deaths are again slowly rising. A surge in infections in 2021 brought down the health system in all 27 Brazilian states, with only 9.2% of the population fully immunized.

Many state and local authorities have rejected the federal government’s laissez-faire approach. State health secretariats created crisis committees and phases of restrictions linked to infection rates and ICU bed capacity. In the northeast of the country, one of Brazil’s poorest regions, governors created a consortium to negotiate vaccine purchases on their own.

But Bolsonaro has lashed out at those who went against the federal government’s plans, blaming their restrictions for the country’s continued economic downfall. Meanwhile, he has urged Brazilians to resist pandemic containment measures, like local stay-at-home rules. In March, during a railroad inauguration event, Bolsonaro told the crowd to “stop being sissies and whining.”

As vaccinations increase around the world, the global economy is slowly recovering. But Brazil’s economic well-being remains at least partially entangled with its still-spiraling health crisis, with local transmission rates spiking, new variants surging, and vaccinations at a slow pace.

“We have no idea what will happen. But we know that we have to at least vaccinate people so we can start living a normal life,” Considera, the economist, told CNN. “By then we can calculate the full effects. But for this to happen, there must be a leader who takes us in this direction, who does the least to combat the pandemic.”