As the last news programme came to a close and anchors bade farewell to their online audience on 3 January, Chris Yeung, the founder and chief writer of Citizen News, gathered together his staff and tried to strike an optimistic tone.

“Remember our very best memories,” he said, dressed in a blue shirt with sleeves rolled up and a crimson jumper draped on his shoulders. “No one knows what will happen next. Don’t worry. Just remember the happy things.”

It was the day 90 largely pro-establishment legislators were sworn in. The previous evening, the independent Chinese-language news outlet of five years said it was closing. It justified the decision citing a deteriorating media environment and concerns for the safety of its staff.

It was a painful decision for Yeung and his editor-in-chief, Daisy Li, to make. “If I am no longer confident enough to guide and lead my reporters, I must be responsible,” Li said last week. “Can we work on some ‘safe news’? I don’t even know what is ‘safe news’.”

She added: “What has changed is not us but the exterior, objective environment.” On 4 January, another outlet, Mad Dog Daily, followed suit and halted operations together with Citizen News.

The latest developments came as no surprise to those who follow recent events in Hong Kong’s once-freewheeling media industry. An exodus of journalists and editors from the territory’s much-acclaimed news outlets, such as Cable TV and its public broadcaster, RTHK, in the last couple of years have alarmed free speech campaigners in the city and beyond.

Barely a week ago, another Chinese-language outlet, Stand News, was forced to close after 200 police officers raided its office and detained seven current and former employees. Two former senior editors were charged with conspiring to publish seditious materials and denied bail.

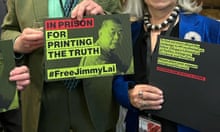

The Stand News arrests came a day after Jimmy Lai, the former owner of the popular tabloid Apple Daily, and six of its former journalists, were given new charges of “conspiracy to print, publish, sell, offer for sale, distribute, display and/or reproduce seditious publications”. Last June, the newspaper was forced to close. State media in Beijing called the newspaper a “rotten apple that plagued Hong Kong for 20 years”. Amnesty International said it was “the blackest day for media freedom in Hong Kong’s recent history”.

Across Asia, the erosion of press freedom has repeatedly made headlines in recent years. In Myanmar, dozens of journalists have been jailed since last year’s military coup. In Thailand, an emergency decree to ban news that “incites fear” was announced after anti-government protests in 2020. And in the Philippines, the country’s most profitable broadcaster, ABS-CBN, was forced to shut down that same year. These incidents are a poignant reminder that even the most successful news outlets could not survive the authoritarian resurgence in the region.

In Hong Kong, once a bastion of free speech within China’s territory, the intensified move against independent news outlets began shortly after Beijing imposed a controversial national security law in the summer of 2020. The legislation drew fierce criticisms from western capitals, from Washington to London. Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, however, said the closure of news organisations “cannot be directly connected” to press freedom in Hong Kong. She also rejected claims of a “chilling effect” in the city’s media landscape.

The assaults on press freedom have continued since the Apple Daily saga. A few days after the tabloid folded, the city’s police chief, Raymond Siu, suggested that a “fake news” law would be necessary to tackle “hostility against the police”. His boss, Lam, announced a few weeks before that her administration was working on “fake news” legislation to tackle “misinformation, hatred and lies”.

“The authorities are just adding more weapons into their pocket in order to stifle dissent,” Yeung said after Siu’s speech in June. “It looks very likely that this proposal of ‘fake news’ law will be put on the agenda in the next legislative session.”

In recent years, the Hong Kong Journalists Association, which Yeung used to lead, has raised the authorities’ ire. Last autumn, the city’s new security chief, Chris Tang, accused the organisation of “breaching professional ethics” by backing the idea that “everyone is a journalist”. In December, Tang gave his full backing to the introduction of a fake news law.

The psychological impact on Hong Kong’s journalists, once regarded as muckraking by many, is evident. A November survey released by Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents Club found that 84% of people surveyed thought the situation had deteriorated since the introduction of the national security law. Some of the respondents admitted to a degree of self-censorship. Beijing accused the trade association of “sowing discord”.

“We are very nervous here for the future of media freedom in Hong Kong,” said Jemimah Steinfeld, a China expert at the London-based Index on Censorship. “It’s hard to believe today that until only recently Hong Kong was the place that journalists at foreign media went to if they wanted to report more freely on China. It’s devastating.”

For young and ambitious Hong Kong journalists, the devastation has been personal. When the police raided Apple Daily’s headquarters in 2020, one of its staff reporters was angry. “I at first was too stunned to even react,” the reporter, Oscar, said in a Guardian documentary that year. “Then that turned into anger as I watched the events unfold.”

Last June, when the nails had been hammered into the coffin of Apple Daily, he met a colleague at the subway platform to share their plans for the future. They greeted each other with a big hug and broke out in tears. “We have never done anything wrong. We have always been doing our part and working hard to make good news. Why did we end up this way?” he said.

Now, at the age of 25, Oscar has put down his pen and works as a photographer in Hong Kong. He said he “grieved” when he left Apple Daily in June. “I [had studied journalism] in college for four years, worked for Apple Daily as part-timer then full-time [for] over four years. It was my dream and passion to be a great reporter, and I did work hard for it. But it turned out to be like this,” he said.

The quick turn of events in his home city in recent years has saddened him. Months after mass street protests that began in 2019, the national security law came into force. The authorities claim such legislation is “necessary in order to secure the long-term stability and prosperity of Hong Kong”, but critics say it is used to stifle dissent and is draconian.

There have been waves of arrests of individuals, from journalists to politicians, who disagree with Beijing and the Hong Kong government. According to Reporters Without Borders, close to two dozen journalists and press freedom campaigners have been arrested since the implementation of the national security law in June 2020. Among them, at least a dozen have been charged or are awaiting the trial. Some opposition politicians, including Nathan Law, once the youngest lawmaker in the history of the legislative council of Hong Kong, are now living in exile.

For Oscar, his transition from a reporter to a photographer was a reluctant one. “This is not the decision I wanted to make, it is the times that forced me to stop being a reporter,” he said. “I still want to be a reporter from the bottom of my heart. I’m not afraid to sit in prison. But how about the people who work with me? Will they sit in, too, because of my work? How about my family and my girlfriend? They’d absolutely be heartbroken.”

It is not only local Chinese-language news outlets that are feeling the chill. International news outlets such as the New York Times are already shifting their base to elsewhere in the region because, according to the US company, the national security law “unsettled news organisations and created uncertainty about the city’s prospects as a hub for journalism”.

Senior officials are now sending letters to foreign news organisations, urging them to support the authorities’ actions. “If you are genuinely interested in press freedom, you should support actions against people who have unlawfully exploited the media as a tool to pursue their political or personal gains,” Hong Kong’s chief secretary, John Lee, wrote to the Wall Street Journal in a recent letter.

“So far, western media still operates with a degree of protection but even this is eroding and many are now choosing Taiwan instead,” said Steinfeld. “The question is: to what extent will they be pushed out, or will they jump? Beijing has been killing the chickens to scare the monkeys, to quote the Chinese idiom, and it is really working.”

At Citizen News, departing journalists have been pondering on their future in these uncertain times. On the eve of the closure, there were tears in the newsroom as well as well wishes.

“We fought the good fight. We finished the course. We kept the faith,” one farewell card read.