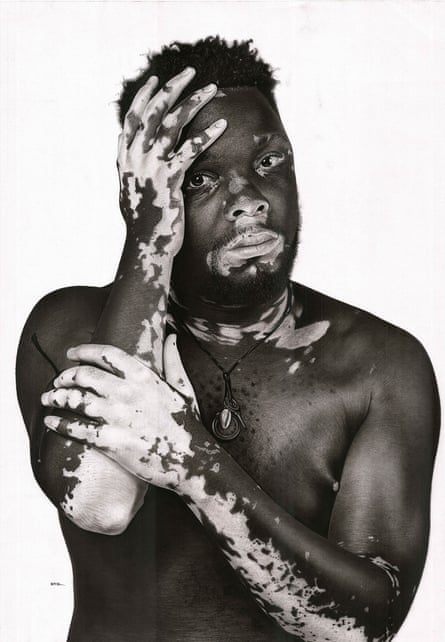

It was a confrontation with a female Michael Jackson fan that first drew Martin Senkubuge’s attention to the skin condition vitiligo.

Senkubuge, a Ugandan artist, was describing his tattoo of the musician to the woman at an art exhibition in Kampala in 2019, when he accused the pop star of bleaching his skin.

The woman cut Senkubuge short, telling him that Michael Jackson had vitiligo – a condition where a lack of melanin causes pale white patches to develop on the skin and can turn hair white. Senkubuge, who was studying industrial fine art and design at Makerere University at the time, had not heard of the disease.

The 22-year-old was shocked to discover the stigma that surrounds vitiligo in Uganda and across east Africa, and how people with the condition were treated.

“People said that persons with vitiligo were cursed and bewitched,” says Senkubuge. “There was a lot of myths and misinformation surrounding them, which was unfair.”

Senkubuge decided he would use his art to educate people about the condition. “Since art is associated with beauty, I said to myself I would draw pictures and models of persons with vitiligo to break this stigma,” he says.

He started reaching out to contacts who knew people who had the skin condition via social media, proposing to draw their pictures. It wasn’t easy.

“I got about 60 contacts, but only three showed up for the photoshoot,” Senkubuge recalls.

But he would not give up. He encouraged those three models to try to persuade others to participate in his campaign.

“I told them my intentions,” says Senkubuge. “I wanted them to pose, stand tall, and be proud of who they are. I told them that art is beautiful and that healing begins from within.”

He managed to secure a small grant of 2m Ugandan shillings (about $560) from the nonprofit Goethe-Zentrum Kampala (Uganda German Cultural Society) to hold an exhibition. In July it finally opened in Kampala.

“It was so fulfilling,” he says. “Despite all the Covid-19 related restrictions, many people turned up. And I am sure those who attended the exhibition now know something about vitiligo.

People with vitiligo are “already beautiful”, he says. “We just want them to believe it.” He now plans to take his pictures, and the campaign, across east Africa.

An estimated 1% of the global population have vitiligo, which isn’t contagious and can be hereditary, caused by an autoimmune disease or trigged by a stressful event, severe skin damage or exposure to certain chemicals. But it gets little attention, largely because it is regarded as a cosmetic condition rather than life-threatening.

Although it cannot be cured, there are creams that can help reduce its appearance. There is very little recognition of vitiligo in Uganda and no official figures on case numbers are collected.

Balinda Musti, 25, who leads the Vitiligo Association of Uganda, which includes 1,000 members living with the condition, says the stigma surrounding the disease means many people try to conceal it.

“They are not really comfortable around people they don’t know,” says Mutsi, who developed the condition when he was seven. “So they will put on clothes that cover the rest of their body, wear makeup and put on glasses.

“Many people here refer people with vitiligo to witch-doctors and other herbalists who claim that they can treat the condition. The witch-doctors will usually recite some enchantments and give the patient some concoctions to drink. Herbalists will smear the person with certain herbs.” But their drugs never work.

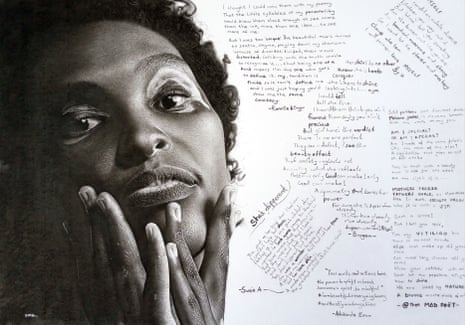

Eve Atukunda, 31, whose image features in the exhibition, has been living with vitiligo since the age of 10. At first, her parents sought help from local herbalists and other traditional healers. But when these people couldn’t help, they turned to modern medicine.

“Different dermatologists would prescribe different creams and supplements. But it didn’t really work,” she says. While the condition is not physically painful, it can hurt mentally, she adds.

“Even when it is developing, you don’t feel pain,” she says. “You just wake up one day and there is a patch on any part of your body. The biggest challenge with vitiligo is that it can be emotionally draining.

“It affects your mental health more than it does your physical health. The condition can make you insecure and diminish your confidence if you don’t have social support.

“There are people with vitiligo who can’t leave the house … who can’t look at themselves in the mirror,” she says.

“I had always been a confident girl, even when I developed vitiligo. But when I was admitted to university I felt different. Students would be speaking and you would think they were talking about you. One time I was in a taxi and the passengers began making comments that my parents had sacrificed me. I got out.”

Atukunda says she wants to see more awareness of the skin condition. “In some tribes, people believe someone with vitiligo ate a particular animal. These myths have to stop,” she says.