Fidel Strub was three when the inside of his cheek started to itch. After a few days, it felt like it was burning, then it began to smell as if it was rotting. A splitting headache came next before his whole body started to feel uncomfortably hot.

“I remember darkness came,” he says. “I had a hammering headache and a burning body. When I opened my eyes, any light stung them and it burned like hell. It was easier to close my eyes for less pain. I could do nothing but lie on the floor.”

Strub was living with his family in a mud hut on the outskirts of Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso. He was one of 12 children and severely malnourished because there was little money for food. His father took him to various doctors but no one knew what the mystery disease was, or how to help. Meanwhile, it began to ravage his face.

Then his grandmother chanced on an announcement on the radio saying that anyone with a child with a hole in their face should go to a hospital in Ouahigouya in the north of Burkina Faso. She took Strub by bus, and there they met one of the only doctors in the country who knew what the disease was, and how to treat it.

Noma starts as a sore on the gums and progresses rapidly, destroying the soft tissues, bones, hard tissues and skin of the face. Without treatment, noma is fatal in 90% of cases, according to the World Health Organization.

Children aged two to six living in extreme poverty with weakened immune systems from malnutrition are most at risk and can die within weeks of the first sore appearing. If they make it to a health facility and survive, they can be left with severe facial disfigurements that hinder eating, drinking and speaking. Where noma is detected early it can be simply treated with antibiotics.

Noma is entirely preventable. When a child has enough food and clean water, the disease is unable to thrive, and is therefore often called “the face of poverty”. That it exists at all is a sign of how society has failed, says Dr David Shaye, of Massachusetts Eye and Ear, who has operated on hundreds of noma survivors in Nigeria. He says: “Noma is a canary in the coalmine indicator of where there are systemic problems with society. It’s a disease of poverty.”

It is a largely forgotten and hidden disease. A search online for “noma” brings up page after page on the Michelin-starred restaurant in Copenhagen but no immediate reference to disfiguring disease. Dr Bukola Oluyide, deputy medical coordinator Nigeria for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), says: “It is assumed to be no longer in existence. Where we see it is where we have poverty and no health centres. It’s only when children are almost on their deathbed with another illness that they [are taken] to a healthcare facility … People do not know they can receive care in the early stages.” Healthcare professionals often miss it completely, she adds.

Strub believes noma remains little known because it affects the most marginalised children in the world and kills quickly.

MSF, with others, is campaigning for the disease to be added to the WHO’s list of neglected tropical diseases. This recognition will lead to noma becoming better known and will make it easier to attract funding to fight the disease, says Oluyide. The ambition is to eradicate the disease by 2030.

Noma is mostly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, though cases have been detected in the US, south-east Asia and South America. It has been recognised for more than 1,000 years and emerged in Europe in concentration camps during the second world war.

Research and data are so scarce that it is impossible to know how many cases there are worldwide, but some estimates put it at 30,000 to 40,000 a year. The WHO estimated in 1998 that there may be up to 140,000 cases a year, and 770,000 survivors of the disease.

Strub is now 30, and feels lucky to be alive. When he arrived at hospital with his grandmother, he was close to death. “The first time my doctor saw me he thought I was dead because there was nothing left on me,” he says. “There was no muscle. I was skin and bones. He fought for two weeks to get me to a stable situation.”

Once he was well enough, Sentinelles, a health NGO , paid for him to have surgery in Geneva. The first operation lasted about 13 hours. In total, he has undergone 27 operations to repair some of the facial damage.

Other survivors reach adulthood before realising that noma is behind their facial disfigurements and the resultant stigma. Mulikat Okanlawon, 37, from Lagos, Nigeria, doesn’t remember much about having noma, but she knows about the aftereffects.

“When I looked at my younger siblings, their faces were different to mine and I knew something was wrong,” she says. “I could only eat [using one side of my mouth], I only had teeth on one side. When I spoke, you had to listen very carefully to get it. I couldn’t look in the mirror because when I did, I cried.”

When she was 14, she was approached by a doctor in the street who told her that she would be able to receive specialist help in northern Nigeria. Okanlawon had had surgery in Lagos that hadn’t worked but travelled with her father to Sokoto where she underwent surgery as one of the first patients of the Noma Children [sic] hospital that opened there in 1999. Now there are plans for a new clinic in Kano, also in northern Nigeria, next year.

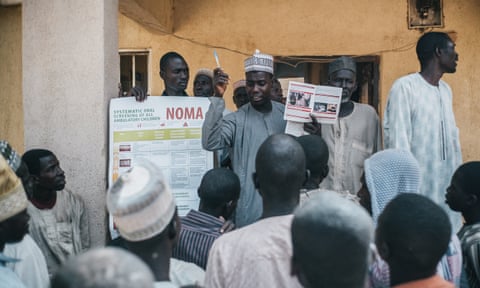

The hospital helps children in the acute stages of noma, and provides surgery for adult survivors. It also does outreach to educate people on how to avoid it in communities where the risk is high. Since it opened, more than 5,000 children with noma have passed through its doors, says Dr Isah Shafi’u, the hospital’s medical director.

Staff have treated more than 50 new cases of noma this year alone. “With the emergence of insecurity and other issues in the country, we have been recording a large number of patients with the disease,” he says. “If a child is displaced, nutrition, a balanced diet and oral hygiene are not there. All of that can lead to a child getting noma.”

Shafi’u wants more help from the international community. “There is a lot to do,” he says. “Noma still exists. We really need help. We want it to be recognised.”

Okanlawon has dedicated her life to helping people with noma. She works at the hospital, supporting patients about to have surgery. “Now I can go anywhere and talk to anyone,” she says. “Where there is life, there is hope. Noma doesn’t have to limit people.”

Strub is also passionate about fighting noma. Adopted by one of the doctors who treated him as a child, he now lives in Switzerland and is president of Noma-Aid-Switzerland, which works to eradicate the disease.

He’s come a long way since noma ravaged his face 27 years ago, but the impact is still there. He has experienced mental health issues, particularly as a teenager. “Everybody’s looking for a good face,” he says. “I really had to accept how I am and learn not to hate myself. Noma is not just a disease, it’s a lifelong battle with yourself.”

Sign up for a different view with our Global Dispatch newsletter – a roundup of our top stories from around the world, recommended reads, and thoughts from our team on key development and human rights issues, delivered to your inbox every two weeks: